A conversation on authority

It was the type of conversation that, in other circumstances, the two friends might have had at a quiet pub, over a couple of beers. But with the pub closed, and travel restricted, Zach and Owen were making do: beers from the fridge, a couple of comfortable office chairs, and a Skype call to bridge the distance between them.

Zach was the one who had suggested the chat. One of his go-to verses, Proverbs 27:17, spoke of how, like iron sharpens iron, one man sharpens another, so he was grateful that Owen had been up for it.

After some opening how’s-the-weather small talk, Owen got them right to the topic at hand: “Okay, Zach, how about you start us off by defining the two sides of the debate as you see them?”

The two sides?

“Sure, I can give that a go. There are all sorts of related issues, but I’m most concerned with the government-ordered church lockdowns. I think we’d agree that we don’t like them – the government shouldn’t be treating the church as “non-essential” or, as is happening in some places, closing churches while leaving bars and strip clubs open. But the real question is, how should we respond to that order? The two stands I’m hearing are:

Churches should listen because we should submit to the government.

Churches shouldn’t listen because the government doesn’t have the authority to close churches.

“I think I fall in with the first group, and from what you’ve been posting on social media, you seem to be in the second.”

“I do probably fall on a different side of this than you,” Owen agreed, “ but I’d define the two sides differently. I think a lot of people are framing it just the way you did, but defining the sides that way also defines away any possibility of common ground: either a person is for listening, or he’s against it. What if it wasn’t two entirely opposing sides, but instead was two different emphases?

God calls his people to submit to authority.

Not every order is an authoritative order.

“Like you, I believe we are called to submission. And when I argue against church lockdowns, I’m not rejecting God’s call to submission – that’s not where we differ. What I’m arguing is that the order isn’t legitimate. If my son ignores what you order him to do, that isn’t a rejection of parental authority. He just doesn’t believe that your orders have parental authority for him. I think this is the same type of thing.”

Two reasons to obey: submission and agreement

Zach nodded slowly: “I appreciate that clarification. Your approach – seeking out the common ground – makes me want to take a step back and see where else we might agree.”

“Sounds good. Why don’t you start us off with why we should submit?”

Zach clicked on his mouse to pull up a document he’d written earlier: “The big reason has to be because in passages like Romans 13:1-6, 1 Peter 2:11-20, Titus 3:1, and Deut. 5:16, God makes it a command. He’s telling us to submit to the authorities that He has put in place, so children should submit to parents; a wife to her husband; the congregation to the elders; slaves to their masters; and citizens should submit to their rulers.”

“Right, and let me offer a second reason: agreement. This might seem to go without saying, but Christians who don’t believe we have to submit to a lockdown order might still want to suspend their church services if members comes down with COVID. I don’t think the government has the authority to issue that order, but I wouldn’t want my congregation to ignore it just for the sake of ignoring it. Listening might be the sensible thing to do.”

One reason to disobey: obeying God rather than Man

“Okay, Owen, we basically agree on those points, but now we’re back to when and why it would ever be right to defy a government order. I can start us off with one ‘reason to defy,’ but I’ll add I don’t think it applies to these lockdowns.”

“Okay, go ahead Zach.”

“In Acts 4-5, Peter and John are commanded by the authorities to stop talking about Jesus, and their response is, ‘we must obey God rather than Man.’ I guess this would be related to what you were saying about not every order being authoritative. All authority comes from God, so if some lower authority issues orders that conflict with God’s own orders, then we should listen to God, and can, in good conscience, ignore the orders from Man.”

“Can you give me an example outside the Bible of that happening?”

Zach smiled: “I’m not going to say the church lockdown but…”

“Go on.”

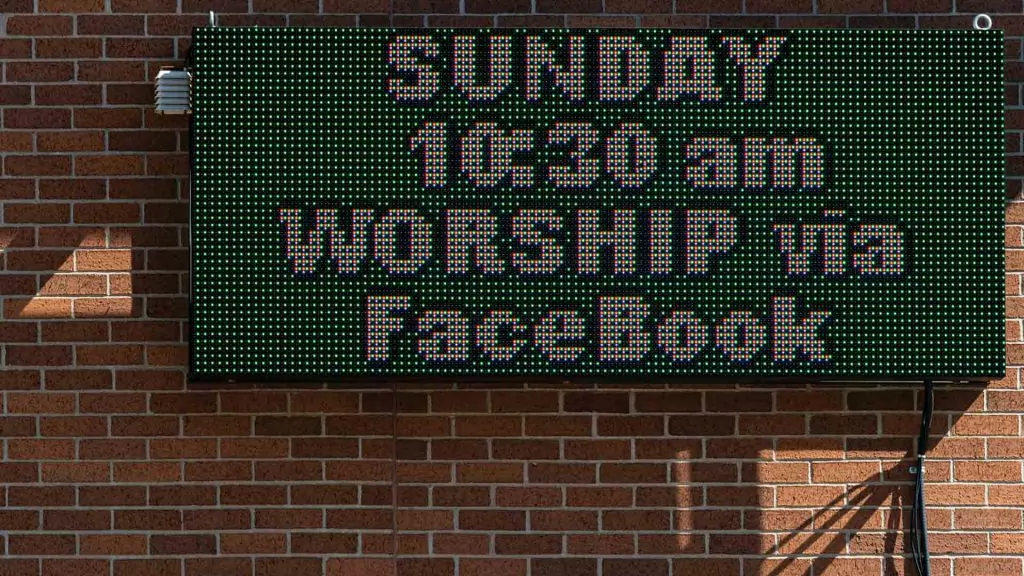

“Well, I’ve heard some people pointing to church closures in China. The government there is ordering some churches to close permanently, and when members defy those orders and continue meeting in secret, I think that’s a case of obeying God rather than Man. But I don’t think you can link that to what’s happening here in the West. China’s church closures are because the State there is deliberately attacking the Church. Our church closures are in response to a health crisis. And our closures are temporary – however long that temporary had been – or only partial, and we can still hear the preaching of the Word via technological means.”

“Can you think of that kind of obeying-God-rather-than-man situation happening closer to home?” Owen asked.

Zach considered the question for a few moments before shaking his head. “No. But it seems like you’ve got something.”

“I do. It’s actually what’s happening on the home front that has me almost happy about these hard conversations that we’ve been forced to have right now. It’s stressful and it's been divisive, but the silver lining – one of the ways I can see God turning this to our good (Rom. 8:28) – is that these are conversations churches and Christians in the West need to have. In the past, submission was our unthinking default. And, I guess, it should still be our default now – I heard one pastor put it this way: when the Church does have to defy the government, our reputation for honoring and respecting the authorities should be such that the government’s response is ‘What? You guys?’ But trouble is coming, and we need to understand the limits of our governments’ authority if we’re going to be ready for it.”

Zach leaned forward: “Okay, you’ve got my attention.”

“The most recent example,” Owen continued, “of a government order that runs right up against God’s commands is the conversion therapy ban that’s been passed in different Canadian municipalities. The gist of it is that pastors and Christian counselors could get in legal trouble for pointing homosexuals and transsexuals to God and trying to help them turn away from their sinful lifestyles. This ban looks like it’ll pass federally too. The government would be telling us to leave these troubled individuals alone. But we’d have to defy that order because our Greater Authority has told us to love our neighbors. Another example might be the Canadian government’s ban on corporal punishment for children under two. God has specifically given us a tool for nurturing and disciplining our children, and the government has specifically said that we can’t use it for the first two years.”

“You want to spank newborns?”

Owen put both of his hands up, and though he was smiling, his voice took on an insistent edge: “I’m not saying that, and I don’t remember when we first spanked our kids. But I am certain that at, say, 18 months, they sure benefited from it. But now, following God’s instructions on this point, we would risk having the State take our kids. That’s scary!”

“Okay, good point. And bad joke on my part. I don’t have kids yet, so I haven’t really thought through spanking, but I think I’m mostly on board with what you’re saying here. I’ve answered a few of your questions, so let me ask you one: do you think there are other reasons we can disobey the government?”

Another reason: the authority isn’t actually in authority

“I do,” Owen said, “I gave the example before that it isn’t insubordinate for my son to ignore orders from you. He has to listen to orders from his parents, but that doesn’t mean he has to listen to orders from any and every parent. It’d be the same sort of situation if the Premier of Alberta started ordering around folks in Newfoundland. They wouldn’t listen, not because they are rebelling, but simply because the Premier of Alberta has no authority over them. Sometimes an authority isn’t actually in a position of authority…no matter what they might be claiming.”

Zach nodded: “Okay, I’m with you so far.”

“So let me ask you a question: in what ways is a government’s authority limited?”

“Well, with your Premier of Alberta example, you’re showing that their authority can be limited by geography – it doesn’t go beyond their boundaries.”

“Anything else?” Owen asked.

“Well, I guess their authority is also limited by things like constitutions and Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms. I’ve been reading about how John Carpay’s Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms is appealing to the Charter to argue that the Alberta government exceeded its authority in their latest round of COVID restrictions. In the US, some churches are appealing to their country’s constitution to argue governors don’t have the authority to shut down church services. But while they’re winning some of those cases, they’re losing others.”

“Sure,” Owen agreed, “but for our purposes here, what’s relevant is that Man’s authority can be limited by Man himself. We can write up laws that restrict what the government can do. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the countries that put the tightest restrictions on their government are ones with a Christian heritage. We remember Samuel’s warning about kings (1 Sam 8:10-22).”

Spheres vs. chain of command

“But,” he continued, “there’s another sort of restriction on government authority that we haven’t talked about yet. A Dutch theologian, Abraham Kuyper, called it Sphere Sovereignty, and it’s the idea that God gave authority, not just to government, but to the family, and to the Church too. When John MacArthur’s church started meeting regularly again, in defiance of California Governor Gavin Newsom’s closure orders, the church issued a statement that appealed to this divvied-up notion of authority. Let me read you something from that statement:

Insofar as government authorities do not attempt to assert ecclesiastical authority or issue orders that forbid our obedience to God’s law, their authority is to be obeyed whether we agree with their rulings or not. In other words, Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2 still bind the consciences of individual Christians. We are to obey our civil authorities as powers that God Himself has ordained.

However, while civil government is invested with divine authority to rule the state, neither of those texts (nor any other) grants civic rulers jurisdiction over the church. God has established three institutions within human society: the family, the state, and the church. Each institution has a sphere of authority with jurisdictional limits that must be respected. A father’s authority is limited to his own family. Church leaders’ authority (which is delegated to them by Christ) is limited to church matters. And government is specifically tasked with the oversight and protection of civic peace and well-being within the boundaries of a nation or community. God has not granted civic rulers authority over the doctrine, practice, or polity of the church. The biblical framework limits the authority of each institution to its specific jurisdiction. The church does not have the right to meddle in the affairs of individual families and ignore parental authority. Parents do not have authority to manage civil matters while circumventing government officials. And similarly, government officials have no right to interfere in ecclesiastical matters in a way that undermines or disregards the God-given authority of pastors and elders.

When any one of the three institutions exceeds the bounds of its jurisdiction it is the duty of the other institutions to curtail that overreach. Therefore, when any government official issues orders regulating worship (such as bans on singing, caps on attendance, or prohibitions against gatherings and services), he steps outside the legitimate bounds of his God-ordained authority… (Matthew 16:18-19; 2 Timothy 3:16-4:2).”

“That’s a lot to take in,” Zach commented.

“It is. But the gist of it is that the Grace Community Church was saying they weren’t actually defying the governor. They were arguing that whether the church opens or closes is under Church, and not State, authority.”

“I think I get it,” Zach said. “They were saying that the authority that comes from God isn’t a chain of command with the State at the top and the Church and family somewhere underneath.”

“Right. And while I think Grace Community is right, I’ll add that the Bible doesn’t make clear where exactly one sphere of authority ends and another begins. I think we’d both agree the State shouldn’t be dictating doctrine to a church, but do they have an interest in public health? And if so, would that give them the authority to close a church in pandemic circumstances? That’s what muddies things: these spheres of authority overlap. To give a different sort of example, it’s a family’s business to raise and educate their children, but if they were to abuse any of those children, then the State’s responsibility over justice would give them authority to intervene.”

Charity

Zach gave one last long draw on his beer before continuing. “I appreciate our conversation, but I’m not sure if it clarified or complicated things for me. So, let me put it to you plain: does a church have the authority to keep its doors open when the State orders them shut?”

Owen gave a tug on his chin. “Would you be satisfied with an ‘I think so’?”

“I guess I’ll have to be. But maybe I can finish us off with something I am sure about, and which I know we can both agree on?”

When Owen gave a nod, Zach continued. “In all of this, we want to honor God, and if we’re less certain about how to do that in some ways, we know exactly how to do it in others. We know what God meant when He commanded us to love our neighbors as ourselves, and to do unto others as we would want done to us. In our COVID/lockdown discussions, it means working at producing more light than heat by assuming the best of, and listening carefully and charitably to, brothers and sisters we might disagree with, just like we’re hoping to get the same back from them. That’s how we can have fruitful ‘sharpening’ discussions. ‘Doing unto others’ also means having patience with the authorities. Most don’t have God’s Word as their guide, so on the one hand, it’s no wonder they’re acting fearfully, and on the other, that might even be a reason for more, and not less charity towards them…even when they are overreaching.”

To that, all Owen could add was a heartfelt, “Amen!”...