The Healing Touch

Be not wise in your own eyes; fear the Lord, and turn away from evil. It will be healing to your flesh and refreshment to your bones. (Prov. 3:7-8)

***

Chapter 1

It was a warm day, and Meggy adjusted her close-fitting cap with a sigh. Its whiteness covered thick, dark braids wound tightly across a high-held head, and enfolded the sides of a well-sculpted face. Meggy felt like itching her scalp but knew that a few steps behind them Hawys, who always walked to church with father and herself, would comment on it. Capitulating to the older woman's unspoken influence, she refrained, and merely adjusted her waistcoast with a shrug of her small shoulders.

"Do not move about so much, child. It is the Lord's Day after all." Hawys' correction came swiftly. Father glanced at Meggy with a sidelong look, and smiled an apologetic smile. He was not one for arguments although she was sure he sympathized. They both knew Hawys did not mean ill and besides that, they were staying in her house, living partly on her charity. "I can hear the Sanctus Bell." Hawys, picking up both speed and her long, dark blue skirt, swept past them.

Meggy automatically increased her steps as well. "Come, Father," she whispered, as she tried to pull him along, "it will not do to irritate Hawys."

Undisturbed, he calmly answered, "Surely the bell ringer has only just begun and we have time to spare." Not multiplying his measured paces, he ambled on, all the while tranquilly regarding their surroundings. Meggy was unsure. Should she stay with father, or should she shadow Hawys? In the end it was the sense of father's words that convinced her. St. Mary's Church was but some ten minutes or so from where they were, and surely the sexton would not shut the doors against them? "Have you perhaps knowledge that the Archbishop himself is attending today? Is that why you and Hawys are in such a hurry, Child?" Father was teasing her. Slowing down, she affectionately squeezed his arm. "It would be wonderful," he continued, "to hear actual instruction from the pulpit. But I confess that I have not much hope for it."

Meggy did not answer. Her eyes were still fixed on Hawys who, glancing back over her shoulder every now and then, was gaining great ground. "We might walk a trifle faster, Father," she suggested, but he seemed not to hear.

"Your mother, although a mite argumentative, was fond of a good sermon, Meggy," he went on, "and I vow that in the long run she would not be in favor of us continuing to attend St. Mary's."

Meggy could see the flint and ironstone makings of the church building coming up ahead. It was a beautiful structure and she loved it. The graveyard at the rear where mother was buried was very peaceful. Betimes she walked there and marveled at the monuments and admired the many stained glass windows that laughed at her from the grey church walls. There was one special window she favored – one with green diamond-shaped panes between its lead outlines. She often stared at that window during services. Sometimes she felt as if staring at something beautiful might reflect into her own heart and consequently make it beautiful. Is that how one was saved?

"Meggy, Child, we are here."

Indeed, they were. To her relief, Meggy saw that there were many folks still entering the rounded-off-at-the-top double oak doors. After quickly looking up at the top of the tower, as she always did before entering the church, she espied the signal beacon, part of an ancient series of signal beacons. "Look Father, the beacon."

She sped up her steps even as she spoke but Father pulled her back. "Easy, Child. The building will not run away." He was forever chaffing her. "Know you that the church was probably built in the 1200s, and rebuilt in 1494?"

She nodded. Yes, she did know that.

"Well, Meggy, now the year is 1672, and that makes this building some four hundred years old. All that time it has stood there and it will very likely outlive us."

"Yes, Father." Meggy lifted her skirts and crossed over the church threshold. Her father followed close behind. The foyer was cool and quite empty. Meggy immediately walked through and on into the church proper. Standing in its wide doorway with the entrance behind her, she searched for the familiar figure of Hawys who was wont to sit in the back on the right. About to enter, a voice made her turn. It was a voice addressing Father.

"Good to see you, James Burnet." It was a low, male voice. She did not recognize it immediately. But as she turned and moved back into the foyer, she saw that it belonged to Timothy Newham, a haberdasher, who lived close to Whitehall. She had never before seen him in their church or, for that matter, at a conventicle. In all probability he was not a religious man.

"Hello, Timothy." Father answered the haberdasher's greeting courteously.

"I had been hoping that you would come by my shop this past week, James."

Father shrugged. Meggy walked back to stand by his side. There was something sad about that shrug and she sensed he needed her.

"You owe me some money, James Burnet, and I am here to obtain it."

"My dear fellow," the reply came softly and courteously, "perhaps you could come by my shop later this week. It seems unfitting to discuss this matter here in church."

"I have waited all of a month already, James, and have seen neither hide nor hair of you."

Meggy could feel the eyes of fellow churchgoers pry into her back. She put her arm through father's. "Let's go on into the sanctuary, Father," she whispered.

"Is this your daughter?"

"Yes, I am," Meggy answered for him, "and I beg you, Sir, do not make a scene here in the Lord's house, for that is not proper."

"Is it proper then to withhold five pounds owing me? Five pounds that have been loaned out for more than three months even though the understanding was that it would be paid back in two months time?"

Meggy took note of the fact that father's breathing was becoming uneven and rapid. And she minded the times of late that he had been tired.

"I have followed you to church, James Burnet," Timothy Newham went on, "and I will follow you inside the church sanctuary if need be, and demand in front of all these people that you give me my money. Perhaps shame will make you pay me back." At the last words, he raised his voice threateningly and it seemed to Meggy that it reverberated off the foyer's high ceiling.

"Come, Father," she repeated gently, "maybe we should go home and we will sort it all out when we get there."

"There is nothing to sort out," Timothy Newham insisted, "Your father owes me five pounds, a tidy sum when you are a poor man such as I am, and I'll wager that he has that amount hidden some place here or there in his shop."

"Not so, Sir," Meggy replied, "and I would ask you to do us the kindness of leaving. Please call at our home at the noon hour tomorrow and we shall receive you properly. You have our word on it."

Timothy gazed at her thoughtfully, gazed long and hard. It made her uncomfortable. He was an older man, and it did not seem fitting. "Very well then," he eventually retorted, "tomorrow it is at about twelve of the hour." He swung about and disappeared through the heavy oak door before a reply could be made.

Chapter 2

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658)

It had been only four years since Cromwell, the Lord Protector, had died. During his time greater religious freedom had come about for the Protestants. However, then “the Restoration” had planted a new ruler on the English throne, a ruler who did not know Cromwell. He was of the house of Stuart and his name was Charles II. Although only a youthful thirty years of age, he was well versed in the vices of the world and his skill in these vices had spilled over into the country.

Countries are labeled - labeled as republics, monarchies, dictatorships or otherwise. But should they be labeled thus? He who sits in the heavens laughs, and holds nations in derision. He has all things under His control and what He desires comes to pass. England breathed laboriously while Charles II ruled and was in great need of a physician.

*****

James Burnet and his daughter stood in the church foyer for a few moments after Timothy Newham had left. Then, as if by common consent, they turned and departed the church building. No words were spoken on the way home. The streets lay silent for the church bells had stopped ringing. Meggy clung hard to her father's arm. James stopped walking every twenty steps or so and reflected on the fact that he had not been able to do as much work lately as he was wont to do. By his side, Meggy wished for the hundredth time that she had been born a boy and that her mother was still alive instead of lying in the burial ground back of the church. How they would both help father. She knew that they would.

James Burnet was a pewterer. Although only a trifler in the trade, there was much call for the items he fashioned, items such as inkwells, mugs, badges, and candlesticks. He was not a wealthy man but small pewter utensils were popular and he sold of his wares to traveling tinsmiths who hawked them in the countryside. The Burnet family had been able to manage. James had taught his daughter much as she was growing into a young woman. Even now as they passed through the silent streets, Meggy could hear his instruction. "Pewter into which no water has come, becomes more white and like to silver, and less flexible," and "Nine parts or more of tin with one of regulus of antimony compose pewter," and "Pewter is called etain in French."

The Worshipful Company of Pewterers in Oat Lane near the London Wall, stipulated that marriage to a member of the pewter guild conferred upon a woman the rights and privileges of the business. Mother, when she was married to father, had been put in charge of the financial side of the business and she had received the payments for all the work father had done. Her receipt to buyers had always been valid. One should not speak ill of the dead, but James' wife, although a hard worker, had clearly not enjoyed the trade and had made her husband's life rather miserable because of it. But she had been capable, and Meggy sorely missed the independence their little family had enjoyed.

The Great Fire of London of 1666

The Great Fire of London had come in 1666 hot on the heels of the bubonic plague, which had hit in 1665. Destroying 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, and St. Paul's Cathedral, the Fire had also burned both Margaret Burnet and her home. The Pewterers' Hall on Oat Lane had been destroyed as well, but it was being rebuilt. James Burnet had not had the money to rebuild his home. For a short while Charles II was blamed for these disasters. Some said his wicked lifestyle had brought about God's punishment on the city; others whispered that the king himself might have instigated the fire to punish the people of London for executing his father.

Although James Burnet had been able to salvage some of his tools, the truth was that he and his daughter were left homeless. Hawys, a distant relative on mother's side, had kindly offered them living quarters. Her son Roger, a great big hulk of a lad, had from the beginning of their moving in, shown great interest in helping his relations. It had become a tacit agreement of sorts that he was working an apprenticeship. But nothing had been verbally agreed upon or signed. James, who was of a very cheerful and carefree disposition, had been glad of the young man's help. Irrationally, seventeen-year-old Meggy had not much liking for Roger and avoided him. Five years her senior, he displayed affection for father and her father returned it. Perhaps she was jealous. If father were to marry Hawys, the trade would eventually revert to her and later, to Roger. And it was a fact that Father was not well. He had of late been fatigued, unable to work much. Also, Meggy had noted that her father had a small, red swelling in his neck. Was he afflicted with a disease? She shrugged her small shoulders again. She did not like to think of such things, but the fears that crept into her mind and the raising of her small shoulders did not push the thoughts away.

*****

Hawys asked no questions when she came home from church but simply laid out the Sunday meal on the kitchen table. Being discreet was a virtue, Meggy mulled, as she helped put the plates and ale on the board, admitting to herself that they were blessed to have such a relative. Although always adamant that they be in church on time, on the whole Hawys was a sweet-tempered woman and a good housekeeper. Father was determined that Meggy obey her in all matters. And rightly so, for did not the household run smoothly under her guidance and were they not clean and well fed? Hawys truly seemed to care for Father and for herself. Was she not even now fixing potions for his ailments, making sure he ate enough and did she not mend his clothes?

Chapter 3

It was Lent. Now is the healing time decreed, for sins of heart and word and deed, when we in humble fear record, the wrong that we have done the Lord. So rang an old Latin rhyme and Meggy had heard father recite it often.

Truthfully, Meggy was not aware that she had ever wronged the Lord. After all, she was quite careful to do all that was right. She obeyed father, loved him and worked hard at the chores Hawys gave her each day. So what was a healing time? She went to sleep thinking about it.

But she had forgotten the words upon opening her eyes the next morning because the early air was filled with the sound of her father's coughing. Turning over uneasily, she listened as the grating noise crept under her bed and agitated the coverlet. Next to the bed, on a chair, she eyed her stay. She only wore it each Sunday and it had been mother's. Disliking its stiffness against her body underneath her gown, Meggy was glad it was Monday so that she could safely tuck the corset away into her dresser drawer.

Hawys' spinning wheel was tucked into a nooked corner

The coughing stopped and, breathing easier, Meggy turned onto her back. Her truckle bed stood at the foot of Hawys' fine feather bed. Hawys always rose at the crack of dawn and Meggy could now hear her rather shrill and drawn-out singing in the kitchen. Father slept with Roger in a side-room off the kitchen. He maintained that the kitchen was too cluttered and busy for him although Hawys was sure that sleeping on a cot in the kitchen would be a great deal warmer for him than the side-room. The kitchen was a room full of pewter, kettles, and skillets, with Hawys' spinning wheel round and annular in a nooked corner. The older woman had been trying to teach Meggy the intricacies and wonders of spinning, but the girl's hands stubbornly refused to convert fibers into yarn.

Stretching her fingers, Meggy sighed and sat up, swinging her feet over the edge of the small bed. It might be a very fine day indeed were it not for the dismal fact that Timothy Newham was coming to see father. Sighing again, she stood up slowly and walked over to the washbasin atop the dresser next to the larger bed. Scrubbing her face hard to wash out the sleep, she pulled on a week dress overtop of her white shift.

*****

"Good morning, Meggy," Hawys stopped singing to greet the girl's entry into the kitchen. A large wooden spoon in her hand, she stood stirring the porridge in a kettle hanging over the hearth. She followed her salutation with "How silently you enter this day, Child."

"I am not a child," Meggy responded petulantly.

"I know. I know," Hawys replied soothingly, "but I do want to braid your hair, big as you are, so come along and stand by the table after you fetch the comb from the side drawer.

Meggy obeyed. She fetched the comb and stood quietly by the table as she watched the smoke from the fire on the hearth channel up the chimney. By and by Hawys came over and began to plait Meggy's hair.

"You are truly silent," Hawys said once more as she put the finishing touch on the second braid, "and now that your hair is done, I would have you wash the front steps before breakfast."

"Think you truly, Hawys," Meggy answered as she stood twirling the left braid with her right hand, "that Father might be ill and that he might... that he might perhaps have the scrofula?"

"He has of late complained of a sore throat," Hawys answered.

"But he could simply just have a sore throat for a while and then it will be gone. That has often been the case with me and with Roger. And I know that you have given him a tonic, and such complaints are common, are they not?"

"As well, there is a small red swelling in his neck," Hawys said softly, hands on her aproned hips as she contemplated Meggy, "but that also is not uncommon. Indeed it could simply be a sting or some such thing. You as well as I know...."

Her discourse was interrupted by her son Roger who burst into the kitchen from the side door. Tall and gangly, he was red in the face from some sort of excitement. "I can obtain a part-time position at the Palace of Whitehall," he broke in on his mother's words. "They are in need of gentleman ushers, seeing that Lent is here and that the king will begin audiences to touch the ill."

"And what about your work for my father," Meggy demanded, letting her braid fall down, even as she emphasized the word my.

"Oh, but I can do both," the young man answered, surprised at her vehemence, "for this work at the palace is only during the healing ceremonies this Lent. I simply help usher the poor into the king's presence and sprinkle rose water in the aisle to offset the stench these people carry. There are a number of young men who will do so. There will be a lot of people attending the ceremonies - from as far away as Russia, it is said. Besides that the work will pay."

Meggy was not listening any longer. Her thoughts had wandered back to her father. "Father needs help all the time, Roger! You cannot be coming and going to ceremonies at the palace. You should constantly be with father and make sure he does not overwork."

Roger looked surprised. His loose-fitting shirt was open at the neck and his collarbone protruded. "What ails you, Meggy? I am always helping him."

"We were speaking of the scrofula," Hawys helped him out, "for Master Burnet has a red spot in his neck...." Again she was interrupted.

"A red spot that could easily be the bite of an insect." Meggy's voice was shrill now and both Roger and Hawys eyed her uneasily. "An insect bite is quite likely," Meggy repeated loudly, "and is it not so, Roger, that you ought to be in the workshop with him right now, at this very moment."

There was a lull in the conversation. Then Roger spoke on. His voice was calm and meant to put Meggy's fears at rest. "It is true that scrofula is called the Evil by many. It is a swollen and ulcerous condition and most pitiful to the eye. I have seen many people with it. Even now the ill are gathering in the streets awaiting the time when they will be allowed into the palace. But it is also said, and I know it to be true, that the scrofula, as well as other ills like it, often disappear of their own accord."

"Well, father does not have it." Meggy stamped her foot on Roger's words as she spoke and then turned, walking past him out of the side door to her task of scrubbing the front steps.

*****

During the next half hour, braids swinging back and forth as she scoured the stone steps, Meggy reflected again that Hawys and Roger were both actually very kind and that she had been rude. It was Roger who irritated Meggy. He was always so sure of himself, both in his demeanor and in his words and there was no doubt that father respected his opinion. She also had to admit, as the suds flew about the steps, that Roger was a fine help to father and seemed to be learning the trade. Perhaps, she pondered on as she swabbed and brushed, she truly was jealous. But jealousy was, as preacher Baxter had often pointed out in his sermons, a foothold for the devil to come into one's heart.

Meggy and her father, as well as Hawys and Roger, divided their worship time between attending the Church of England and patronizing conventicles, even though conventicles were forbidden by law. Only five people, the law said, were allowed to meet together outside of the state church. Any larger number gathering for another church service was deemed illegal. Sometimes conventicles were held in the house of someone they knew, and at other times they were held in open fields.

Meggy paused, wringing out the scrub cloth with her hands. Even though she admired St. Mary's Church, she also liked meeting out in open spaces, hearing pastors fervently extol God's goodness, and singing in the fields with only the sky for a ceiling. Watching the water drip down the steps, she wished that worries would run away as easily as the water, for there seemed to be so many of them. The worst of them was the fear that Father might have the scrofula, but hard on its heels was the fretting, the worry that had the name of Timothy Newham, the haberdasher, attached to its label.

*****

After brealfast, Meggy was called into her father's workshop. "I owe Timothy Newham," he began, stopping rather abruptly and averting his face from her anxious gaze, before continuing, "I owe Timothy Newham," he started again, "some money, Meggy. I'm sorry, but there's the truth of it."

He bent his head in such a way that she could clearly see the small red swelling in his neck. "What are we to do, Father?"

"Well," her father answered softly, thoughtfully turning over a little pewter salt-shaker in his hands, "Hawys has graciously offered to pay the sum I owe and I would like you to deliver it to him. I would rather he did not come here, Meggy."

"You want me to deliver the money to Timothy, Father?"

"Yes, Child."

"But how are we ever to repay Hawys, Father?"

"I am going to marry her, Megs." Father only called her Megs when he was very moved and she intuitively felt she ought not to say anything which could trigger more emotions in him.

"Hawys is good to us, is she not?" she managed, "But five pounds is but a little to build a marriage on surely?" He nodded and emboldened she went on, "Do you love her, Father? Do you love her like you did mother?"

Actually Meggy was not sure whether or not her father had loved her mother. There had been many arguments between them. And the truth of it was that she had never yet heard him arguing with Hawys. But how had it come about that father owed Timothy Newham money? Timothy was a haberdasher and dealt in thread, tape, ribbons and other such things as a milliner also uses. His wares were in demand. She had been by his shop on occasion, sent by Hawys for something or other, and she had seen that the counter and the shelves in the haberdashery were crowded untidily with many things – things such as drinking horns, knives, scissors, combs, chess men, knee spurs and even girdles. Her mind had been turned topsy-turvy with the disorder in his store. There were so many items lying about that one's eyes became confused.

"Why do you owe him money, Father?"

"He had bought some tin in Cornwall, Megs, and he sold it to me for what seemed like a decent price at the time and I just have not been able to repay what he lent me for it."

"Oh."

Roger walked into the shop right into Meggy's “oh.” After looking at them for a moment, he began oiling the pewterer's wheel. The conversation fell silent. Father handed Meggy a small linen bag.

"Go, Child," he concluded their discussion and then, turning to Roger, "I have some items for you to carry to Lion's Inn."

Chapter 4

It was a fine morning and Meggy enjoyed walking. Timothy Newham's haberdashery was a good stretching of the legs away but she was young and relished the long stroll using the time to both look about and to think.

Father's calling was to be a pewterer.

Father's calling was to be a pewterer. Timothy's, on the other hand, was to be a haberdasher. Haberdasher – she repeated the word in her mind. It was a strange word but it was Timothy Newham's calling. And what was a calling? Calling was using one's voice but it was also something else – actually two other things.

“There is a general calling,” father's voice plainly rang in her head, “for everyone. And that is a calling to conversion and holiness. Are you being called, Meggy? Are you God's child?” Father had asked her this question several times and always she had nodded in response, answering, “Yes, to be sure, Father.” But father must not have been satisfied with her sincerity, because he touched on the subject again and again. Was she converted? Was she holy?

Even now as she walked the road, she pondered on the question. Truly, she did all things required of her, did she not? And did this not make her holy? She heard father's words again. “All those who come to church and sit in pews, Meggy, are not necessarily converted. To sit in a church does not mean you have been touched by the Spirit of God, Child.”

Meggy lifted her skirts to avoid the blackish droppings of a horse straight on her path. Although she stayed close to the buildings, the filth of the streets was difficult to avoid. She was a little nervous too about the rats that scurried through the muck and grime. Of a certainty, father had told her often enough, the accumulation of waste had helped cause the Plague. If everyone would scrub their steps, as Hawys made her clean their steps most mornings, surely the problem would be less. She lifted her skirts again. It was hard work to live and maintain a family in London.

She fell back to contemplating. “There is also a particular calling,” father's voice continued on in her head, “for every person, Meggy. And that calling consists of the specific tasks and occupations that God places before a person in the course of his daily living. It might be the work a person does for a living. For me that would be the work or calling of pewterer.”

“And what do you think the particular calling is for me, Father?” she had countered, leaning cozily against him as they had sat talking in front of the hearth.

He had stroked her hair as he replied, “It might be that of cooking, cleaning, listening to someone's troubles, or smiling.”

“Smiling?” she had interrupted sitting up straight, almost laughing at the silliness of the suggestion. “Shall I stand at a booth, Father, selling smiles for ha'pennies to passersby? How could that be?”

Father had laughed as well. “You see, Daughter,” he had explained, “you are good at smiling. Quite good, truth be told and God has given you smiles to bestow as a gift to others. Pastor Baxter, whom you have often heard at the conventicles,” he went on, “says there is a difference between washing dishes, scrubbing steps and preaching God's Word; but as touching to please God, there is no difference at all. Do you understand this, Meggy?”

She had nodded.

*****

"Hello, Meggy."

All the while thinking and walking, she had almost bumped into Timothy, the haberdasher, who was standing in front of his shop window. Timothy's particular vocation, Meggy pondered on for a moment, was being a haberdasher. Of course he was also called to holiness, called to be a child of God? But he never....

"Are you dream-walking, girl?" Timothy spoke in jest as he looked approvingly at the blossoming young girl standing in front of him. Indeed, Meggy was pleasing to the eye. Red-cheeked, shining black braids bounching on her shoulders, clear, bright blue eyes warmly embracing her surroundings, she was a picture of health and self-assertion. Yet, at the same time, there was a shyness about her that appealed to the much older man.

"I've brought you your money, Sir," she responded hesitantly after staring at him for a moment, reaching into the deep pocket of her skirt. Pulling up the small linen bag with the five pounds, she added, "Here is the money which father owes you."

"Well, I was ready to walk to your house, but will not deny that I am happy you came here. It saves me both time and effort. Will you not come in for a minute while I make sure that all is accounted for?"

He opened the door to his shop and extended an arm downward in welcome. Although she did not want to enter, she considered that the matter ought to be settled. Passing in front of him, she entered the haberdashery. Again, as before, the cluttered mayhem of his store overwhelmed her sense of orderliness.

"Please sit for a moment," Timothy said, following her into his shop and, wiping the dust off a wooden stool. He indicated that she should make use of it. Lifting her skirts once more, she obliged. "It's a bit messy, I own," he continued, "and I warrant, it could use the touch of a decent woman."

He eyed her for a moment before emptying the money into his right hand. Counting it, under his breath, he quickly ascertained that the coins added up to the right sum. "Do you want a receipt?" he went on to ask, "and might I also inquire if you left your father in good health this morning?

"He's a bit poorly," she responded, before calling to mind that surely Timothy did not really care about her father's health, for if he had she would not be here now with the linen bag containing the money that he had demanded so crudely in the church foyer yesterday. "Yet he is well enough," she hastily appended.

"I've just had a consignment of lace come in," Timothy volunteered the information slowly, regarding the girl as she sat on the stool, "and I'm thinking that a bit of lace would look fetching on your dress, Meggy."

He spoke familiarly and it made her uncomfortable so that she gazed down at her hands without responding to his words.

"Well then, you must be worried about your father," he went on, "for I call to mind that it is as you say, he did look a bit unwell the last few times I saw him.

"He is well enough, Sir," Meggy defended, albeit in a flat tone, eyeing both the floor and the nearby door, hoping that the receipt would be forthcoming soon.

"I expect that you've heard that the king will be coming to Whitehall later this week."

"Yes, I have."

"Indeed, he's come for the healing ceremony during this Lent. I am glad that you have heard of it." Timothy's eyes rested so long on Meggy that she nodded and he spoke on. "I'm surprised you're not more animated by this. The practice of healing by a reigning monarch such as King Charles II assuredly is common knowledge and I've no doubt you'll be wanting to take your father."

"No, Sir." But Meggy's voice was unsure and Timothy was quick to latch onto it. He went on capturing her imagination with his words. "The practice of the 'healing touch' was first recorded centuries ago by the historian William of Malmesbury, who related the story of a barren wife. This wife, whose back was covered with ulcers, dreamt she was commanded to go to King Edward for a cure. So she traveled to court. The king, who much desired to help the poor woman, touched her back with water and her ulcers began to heal within a week's time. Not only that, but upon returning home, she was delivered of twins within that same year."

Timothy stopped his narrative and considered Meggy's face. During the short discourse, he noted that she had become fascinated hanging onto his every word. Pleased and flattered, he continued, his voice lowered as if confiding a secret. "There have been other tales as well, including one in which King Edward carried a beggar on his back. The beggar was a cripple. The king carried him into St. Peter's church at Westminster after which the beggar was cured."

"Is this true?" Meggy asked, eyes round, "I have always been taught that only God can effect a change in disease, so is it not false to say that earthly kings are able to effect cures?"

Toffee-nosed, Timothy smiled down at her. "These ceremonies are extremely religious in nature. God gives kings this gift of healing as proof positive that they are chosen by Him to rule. So you need not worry about doing something that is wrong. Now if you are worried about your father's health...." He left the sentence unfinished and seeing her face become eager with hope, he continued in a scholarly tone, "Well then, I would advise you to look into going to Whitehall tomorrow."

"Whitehall? Me?"

"You speak, Meggy, as if you could not go there. But you could, you know. There are many who will go there."

"But Father is not ... and I'm sure he wouldn't go. Besides I don't even know how I could get in." She stopped and shook her head before going on. "And I don't even know if what you are saying, Timothy Newham, is true. It could all be false and you could be telling me a tale."

"There were years, it is true, that kings did not touch anyone. And that is probably why you, being some years younger than I am, are not as familiar with it as I am. During the time of Oliver Cromwell the practice was not in vogue at all. But now that a true king rules England once again, the touching ceremony has come back as indeed it should. Parish registers are kept and miracles have been recorded. My uncle is one as who keeps such registers. That is how I know."

"I do not know if I ought to believe you or not." Meggy's voice was unsure.

"Well," Timothy responded, looking with pleasure at the roses appearing on Meggy's cheeks in her agitation, "all I can tell you is that I can let you have a ticket so that you can enter Whitehall to listen to the ceremonies that will take place tomorrow. If you like what you hear, perhaps the day thereafter...? " He left the sentence dangling.

"How is it that you can get such a ticket?"

"I told you that my uncle, Robert Newham, is a registrar and he is one who gives out tickets and he has permitted me to sell them to such as are in need of healing."

"Tickets?" Meggy responded, "and pray tell how much do these said tickets cost? And the truth of it is that I myself am not in need of healing."

"It would not cost you anything, for I will gladly give you such a ticket."

"You would?"

"It makes me glad to see a daughter care so much for her father as you do for yours, Meggy."

"He is not really ill, you know," Meggy responded rather feebly, "but it would do no harm...." She stopped before she added softly, "He would not go though. I know he would not."

"Perhaps," Timothy suggested softly, "you might attend with me tomorrow, might attend the first ceremony at Whitehall to see for yourself what happens. Then, I am sure you would be persuaded of the reality of the cures effected by the king's touch. And being persuaded, you could easily convince your father to go the second day."

"He is not convinced easily," Meggy responded, all the time seeing the swelling in her father's neck grow.

"But you could go with me," Timothy let the words dangle like a carrot in front of her, before he went on "and see for yourself what happens."

Meggy did not respond.

"It is not an evil thing, Meggy. Gentlemen Ushers prepare the banqueting hall over which the king will preside. These ushers usually spray a perfume of sorts so that the stench of the ill will not overcome either him or bystanders. Next the Yeomen of the Guard bring in the sick, one by one, and they stand in the aisle before the king's place of sitting. It is after this that the king enters and sits down on a chair of state. His personal confessor, the Clerk of the Closet, will be standing at his side. The Prayer Book is placed on a cushion close by. You see, Meggy, it is all very religious and honors God."

The girl said nothing, but her eyes were brimful of curiosity and wonder.

"The Clerk's assistant," Timothy went on, "has gold medals or 'touch-pieces' hanging on ribbons on his arm. There are also two royal surgeons nearby waiting to escort the sick from the aisle right up to his majesty so that he can touch them. He strokes their necks, you see, in a loving way as they kneel in front of him, prior to their being healed." He stopped his oration and Meggy was torn. The words sounded so very good, so very real and so very loving.

"I will go," she suddenly spoke decisively, "I will go with you, Timothy Newham, if you will be so good as to take me so that I can see and hear this firsthand. But I must hide this from Father and Hawys for surely they would think it nonsense. They are not overfond of the king, as you must know, but they do think that prayer...."

She stopped and looked at the cluttered counter. So indeed was her heart cluttered, for there were so many things in there that she could not quite see straight. There was something askew with what Timothy was saying, but she could not manage to put her finger on it. “Whether you are well or sick, Meggy,” she could hear father say, “tis the Great God Who brings your state about. He is the One Who prevents sickness or brings it.” She nodded to herself. Yes, here was a bit of uncluttering. Again she heard her father say “Sometimes we are made ill, or someone we know is made ill, to test our faith and patience, Meggy.”

"Well, Meggy," Timothy's voice interrupted her thoughts, "if you are of a mind to go with me to Whitehall you must be here at about one of the clock tomorrow. And perhaps the next day you can persuade your father to come with you. Be here promptly and I will be glad to be of service to you and your father. What can it hurt, after all, just to go and have a look?"

This was true. Just looking and listening. Where could be the harm in that? She slowly slid down from the stool and stood directly in front of Timothy. He could possibly be an instrument in the hands of God to give her opportunity to help make father better. "I will be here at one of the clock tomorrow," she returned, walking past him out of the shop, not noting that the corners of Timothy's mouth had turned up, exposing square, yellow teeth in a half-smile - a triumphant smile.

Chapter 5

Meggy had to tell an untruth at the evening meal in order to be able to leave the house the next afternoon. Allyson, the chandler's daughter, she mentioned to Hawys, her mouth full of pottage, had asked her help in making soap because her mother was ill with the ague.

Roger stared at her in a strange way, a sad way almost. It made her feel rather awkward and she swallowed her mouthful with difficulty, because it seemed as if Roger knew that she was lying and that he was disappointed in her. But father smiled a broad smile and commented that this was most kind of her and of course she should go and help her friend.

*****

Bells marked the one o'clock just as Meggy rounded the corner of the haberdasher's street the next day. Timothy, who was just closing the door of his shop, saw her coming. A smug look appeared on his face. Turning, he offered her his arm. She stopped short, confused by the gesture.

"Come, come," he said, "you are young and must be escorted. I promise I shall take good care of you."

When she still made no motion to take his arm, he scratched his head with his left hand. She marked the dirty fingernails on it. Then he remarked that he had forgotten something of import in his shop which she might find appealing. Stepping back, he unlocked the door of his store.

"What have you forgotten?" she asked.

"Oh, something you might find interesting," he replied, "Come in and I'll show you."

A tad uncomfortable, but curiosity overcoming her sense of acceptable behavior, Meggy crossed over the threshhold once more stepping towards the counter. Timothy closed the door behind them. The click of the latch and the rather musty smell of the place straight away awoke her to the impropriety of the situation. Timothy moved a few paces into the shop. Then he sidled back and stood in front of the door. Particles of dust settled down on the counter. Suddenly extremely anxious, she stood stock still, wishing with all her heart that she had stayed outside. Timothy inched a bit closer.

"You know," he mouthed, "you're a very pretty young lady."

Meggy stepped sideways. Even though he was still some four feet away, she could smell his sour breath.

"So what I forgot to collect was a reward for helping you get into Whitehall," he went on in a rough whisper, "and that reward is just one little kiss."

"No!" she whimpered. Her voice had lost its ability to speak loudly, her heart pounded and her hands had turned clammy with fear. She continued pathetically, "Open the door and let me out. I don't want you to...." She did not finish for he had moved forward, had put his hands around her waist and was pulling her towards himself. It was at this point that her voice regained its strength and a high-pitched piercing sound shook the objects on the counter. It flew through the cracks in the wall out into the street. Straightaway the hinges of the door almost flew off their frame as it was flung open. Roger's lanky frame stood tall and forceful in the opening and Meggy had never been so happy to see him.

"What's going on here?" he yelled, shoving Timothy into the counter, knocking bows, ribbons, pins, needles and lace onto the ground.

The girl immediately slipped past the men, and ran down the street. Her cap was askew and her cheeks were crimson. She did not know where she was going and she did not care. All she knew was that she had to get away. What had she been thinking? What had she done!? Passersby stared. She neither noted nor cared. Finally, out of breath and underneath the overhang of some roofs, she stopped. What a ninny she had been! And what should she do now? She trembled with the horror at the thought of what might have happened. A few minutes later Roger caught up with her.

"Meggy!! It's all right. Timothy Newham won't be bothering you again."

Without looking up, she began to cry. Roger's arms folded around her and her head leaned heavily against his bony shoulder. "He's a beast," she sobbed, "He's horrible. He ...."

"I know," Roger soothed, "but you ought not to have gone in there, Meggy. It's a good thing I was due to go to Whitehall and happened to pass the shop. To tell you the truth, I followed you. Both Mother and I were worried. We knew that Allyson's mother was not ill. So we wondered...."

She pulled away, her tear-stained face angry. "But I went to Timothy Newham for father, Roger. He was going to take me to the ceremony. I thought that if the king was giving out the 'healing touch' about which Timothy seemed to know so much, then I ought to find out as much as I could about it. I thought that father ought to... ought to have a chance to... and Timothy said he had tickets."

Roger's face became grim. "Surely you didn't believe that chicanery. Timothy Newham is a deceitful man, Meggy. As well, he and the king are both lechers. The king wants to be popular with the people. He wants them to like him. They call him the 'Merry Monarch' but he wants to hide the fact that he is... is....." Roger almost choked on his words, incredulous that she would fall for the jiggery-pokery of such a fraudulent royal ceremony.

"But you," Meggy countered, wiping her face with the back of her hand as she spoke, "would work at Whitehall at this ceremony and would thereby help people enter deceit, if what you say is true."

"Yes," Roger conceded, "to make some money to help your father and yourself and, of course, my mother. But maybe you are right and I ought not to have such a job." He stood for a moment, gazing down at her, and then repeating, "Yes, I ought not to have taken the job. I was wrong. Nevertheless, I think I will take you to the palace so that you can see for yourself what it is about."

"You would take me there?"

"Not so that you could take your father there, but so that you can see that you ought not to trust in men, Meggy."

She was silent and hung her head. Taking pity on her, Roger went on a little less vehement.

"You have heard good preachers often enough, Megs. Remember, their message. We, all of us, are diseased and full of infirmities. This is not such a strange thing here in this world. If your father is indeed ill, and God forbid that it is so, we will use such means as He provides for healing. But God does not use the wiles of such men as Charles II to heal folks. The ill vagabonds that flock to him, wretched creatures such as I see in the streets, only come because Charles provides them with a coin, a 'touch piece.' That is what they call such a coin. Most sell this coin as soon as they leave the palace and use it to buy food or who knows what. Some perhaps really and truly believe that Charles is sent by God to heal them. But would God use black to make white? I think not! Oh, Megs, wake up and trust God!"

Roger had unconsciously used her father's pet name for her and she blushed. He continued with a last admonition. "And do you really think that your father would go with you to such a ceremony as would belie his faith?"

Chapter 6

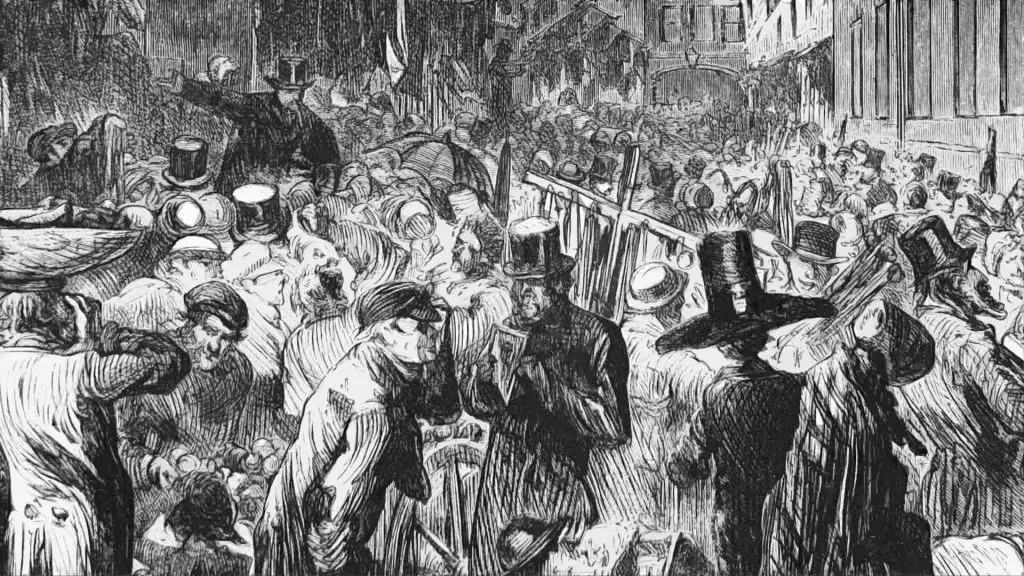

There were many beggars lined up by the gate at Whitehall. A host of them had swellings and lesions in their necks. Meggy tried not to stare and pressed close to Roger as they walked past them. Surely Father, she thought, was not as badly off as these people. Actually, he was not like them at all. She came close to rubbing shoulders with one ill wretch who had yellowish fluid oozing down the side of his legs. Her stomach turned.

"Come, Meggy," Roger said, "don't stop and don't look so scared."

"I'm not scared," she answered in a small voice, even as she eyed an emaciated woman with an ulcerated mass just above her shoulders. Next to the woman, a young boy lay convulsed on the ground, his mother desperately trying to pick him up. A blind man stood behind them.

"Come on, Meggy," Roger repeated, "walk quicker."

The disfigured disabled her feet. Was the king, she wondered, really such a wonder-worker as to be able to perform miracles? Such a wonder-worker as to heal these unfortunates? Did he have such a closeness to God as to cure these desolates and woebegones? Was father a such a one?

"We are nearing the Banqueting Hall," Roger said, "and that is the place where the king will come to touch. One by one these poor creatures will be brought before him. They will kneel before the king and he will stroke their necks."

Meggy shuddered. She knew not whether it was the thought of the king actually touching the misery around her that caused her to shudder, or whether it was the thought that it seemed blasphemous on the king's part to think that he had power over illness.

They had reached the entrance to the palace and Roger pulled her off to the side. The queue, of which they were not a part, lay both behind and next to them. It was filled with crutches, bandages and disfigured persons. All of them were holding certificates verifying that they would be allowed into the king's banqueting hall.

A man hobbled by to the right of them. He was disfigured in an appalling way. Growths of a most horrible kind hung from his neck, dripping both greenish pus and blood. In his dirty hands he clutched a crumpled ticket of admission. The ticket had been, if what Timothy had told her was true, signed and sealed by a minister or church warden declaring that he had never before been “touched” by the king. Despite her revulsion, Meggy ached for the man. He appeared so very ill. Yet there was hope in the very manner he put his feet down, put them down steadily towards the entrance of the palace. Mesmerized, she could not take her eyes of him. It was almost his turn to be admitted. A Yeoman of the King's guard, one who conducted all the ill to a line attended by the surgeon, was also watching him and Meggy read loathing on the guard's face for this particular man. But the man himself noted nothing. His whole being was simply fixed on entering the banqueting hall.

"Hey, you! Let me see your certificate." The Yeoman's voice was loud enough so that Meggy could hear each word. Startled, the deformed man handed over his paper to the guard who, after scanning it, threw it to the ground.

"It's forged," he announced in a gruff voice, "and I can tell because of the blood on it. You think that you can enter by smearing blood on a piece of paper and not be caught?! You were a fool to think it! Away with you!"

Meggy heard a sob catch the man's throat as he watched his paper flutter to the earth. His face ruckled and his eyes, sunken in their sockets, produced tears. What a poor wretch he was!!

And it suddenly came to her that she was such a wretch too. And it came to her also that surely this was not the way it should be and not the way it was. Had she not but recently heard pastor Baxter say that you could not let yourself in at the gate of heaven, and that you could not pay your own way into the banqueting hall of Jesus? She had not really understood the words at the time but she understood them now. Pastor Baxter's voice rang clearly in her head as she continued to behold the spurned man. And she beheld herself. “Take heed to yourself,” she heard pastor Baxter say, “for you have a depraved nature. You have sinful inclinations, Meggy! You are verily ugly in nature. And think you that you can come into heaven by your own strength?”

Meggy sighed a deep sigh. She recalled her jealousy; she knew that this very day she had lied to her father and to Hawys; and she remembered that her curiosity had almost caused her bodily harm but less than one hour back. Indeed, she was a wretch! Of a certainty, at this very moment she had lost her desire to enter Whitehall and kneel before Charles II. But she did have a deep desire to worship. Indeed, her heart was bowed low within her. It all depended, she thought, whom the king was. To be sure, was it not so that no one needed a certificate to come into the true King's presence. All that was needed was the blood of the Lamb of God. "Therefore, ... we have confidence to enter the holy place by the blood of Jesus ..." Was that not what pastor Baxter had spoken on the last time she heard him at a conventicle?

Roger poked at her arm. "Meggy, what are you staring at? Have you seen enough, girl?"

She smiled at him. It was a tremulous smile. It was a contented smile. It was the smile God had bestowed on her as a particular calling.

"I have Roger.”...