For Geoffrey Thomas, my tall friend in Wales, who related an anecdote and gave me the idea.

*****

In the craft of sewing, things are often joined together with stitches. There are a great many different types of stitches – the ladder stitch, the running stitch, the blanket stitch, and the feather stitch, to name but a few. The straight stitch is the most common stitch used in sewing. Thread is pushed through two pieces of fabric and pulled until the end knot catches and the cloth comes together. Straight stitches are used to form unbroken lines.

Even so in the craft of predestination: the great Creator of the universe breathes threads of events through lives so that creatures will be drawn tightly to Him, so that they will be conformed to His image in an intricate, but straight pattern. God’s children are indeed fearfully and wonderfully made.

*****

There was no more butter to be had anywhere. Vegetables had become a forgotten commodity. And who could remember the color of cheese? Meat coupons, coupons which had been rationed out to everyone in the small villages of western Holland, were not worth the paper they were written on, and the bread allotted to the skeletal townsfolk still walking about was a mere 1,400 grams a week. The grim winter of 1944 had set in and its cold was colder because bodies were so much thinner. Roads were closed. Railroads were not functioning. Nothing moved. There was no food, no fuel, and many families were beginning to burn their furniture and their books in order to keep warm.

Luit Adriaan had stopped shaving, had for the most part stopped talking, and had acquired a lifeless hue in his eyes. His older sister, Ellen, regarded his stubbly, half-bearded face with a certain degree of anger.

“You have given up,” she said, even as she bent over a pan of water mixed with four grated tulip bulbs, stirring both angrily and persistently as though her very life depended on it.

She had handled and peeled those bulbs as if they were precious cargo; had cut them into halves; and had carefully removed the little yellow core at the center that everyone knew was poisonous. And perhaps her life did depend on this work because the tulip bulb mixture cooking there in the pan of water, together with a single browned onion and a little salt, would be the main and only course of supper that evening.

Besides having given up on shaving and talking, Luit Adriaan had also stopped trudging about on the roads, and had given up on knocking at farm doors asking for handouts. People often shut their door, even locked it, when they saw him coming. Even more difficult to take than this refusal was the fact that very few people smiled at him. He knew why. It was not because there was absolutely nothing left on farm pantry shelves, but it was because during the early months of this year Lux, his brother, had been exposed as collaborating with the Nazis. Caught and shot by the underground as a traitor, the name Adriaan was steeped in shame. There was more than one person in the village who attributed the death of a dear one to Lux. Luit sighed deeply leaning his face on top of his hands. There was something in the dull expression of his eyes that both angered and grieved his sister.

“You must not give up,” she repeated, although switching her words to a command.

Behind her, the kitchen door opened and Nelleke, her sister-in-law, walked in. Nelleke’s belly, which should have been as round as a melon at harvest time, barely dented her apron and made the dark blue maternity dress underneath that apron seem several sizes too large, ill-fitting, and clownish.

“There Is some tea,” Ellen Adriaan breathed the words softly, even as she moved away from the stove and pulled out a chair from behind the table for Nelleke.

Actually, it was not tea but a concoction of sugar beet juice. She poured the purplish liquid into a teacup and placed it in front of the girl. “Drink,” she ordered, “You must drink a lot.”

Nelleke obediently lifted the cup to her mouth and slowly sipped. The hot liquid stained her lips. Then she put the cup back onto the saucer. “Luit,” she said to her husband, “Luit, we haven’t talked about it but what shall we call the baby if it is a boy?”

Luit somberly regarded his wife from his place across the table. His eyes softened for a moment. “Norbert if it is a boy. Norbert for father. Father,” he added softly, taking his eyes off his wife and addressing his sister for a small moment, “was a good man.”

Feeling that the sentence was an accusation of sorts, Ellen turned her back on him.

“And if it’s a girl?” Nelleke asked.

“Nora.”

Nelleke lifted the teacup back to her lips and took another sip. The kitchen door opened again and Adam walked in. Adam was nine years old and wavy brown hair, very like that of his Oom Adriaan, fell over his forehead. But unlike his uncle, his eyes were alive. On thin but purposeful legs, the child proudly walked over to his Tante Ellen, pulling three dilapidated carrots out of his pocket.

“Meneer Ganzeveer gave them to me for you.” His voice was eager, rather as if he expected a pat on the head, an approval of sorts. But she had no comments and did nothing to show the boy that she was pleased with his acquisition.

“I think he rather likes you, Ellen.” Luit gave his opinion in a half-joking, half-serious manner, adding, “But I think you should be forewarned that he might be a dangerous man. He reminds me of Lux.”

Ellen treated his comment as a joke and grimaced, for she secretly admired Mikkel Ganzeveer even though he was suspected of dabbling in the black market. “Sit down, Adam,” she said, taking the carrots from her nephew’s hands, depositing them on the counter as she spoke, “and you can have some tea too.”

Adam pulled out a chair next to his Tante Nelleke, who laid her hand on his shoulder and smiled at him when he slid into place. He smiled back at her.

“Soon your baby will be born,” he said in a whisper and rather shyly.

“It will be your baby too, Adam,” she answered, “and I’m sure it will love you.”

“You will have a small cousin,” Luit added, “and that means you will have a great deal of responsibility.”

“Responsibility?” Adam questioned.

“Yes,” his uncle said, “because if Tante Nelleke or myself are not there, it will be up to you to take care of the baby.”

“Not here? Up to me?”

“Yes,” his uncle answered, his eyes looking straight into Adam’s eyes, “up to you.”

After a few seconds, he added persistently, “Do you promise that you will look after this baby if you have to, Adam?”

His sister made a derisive sound with her tongue. She liked not this talk. It was defeatist and it also, she innately realized, put her down.

“I promise,” Adam said, unable to look away from his uncle’s gaze.

*****

That night Nora was born. She weighed very little, and only mewled a pitiful birthing cry. And God pulled the stitch of that cry straight through that night so that even when it appeared to be a given that the child would not see the light of day, it turned out quite differently. Tucked away between wool blankets, eyes wide open in a paper-thin, blue-veined face, Nora stared up at her Tante Ellen.

However, It was so cold in the bedroom that the water in the washbasin had frozen solid and Ellen Adriaan, although she applied all her midwifery skills, could not keep Nelleke from dying.

Luit, hunched over on a chair by his wife’s bedside, wept soundlessly, tears rolling down his cheeks. His hand would not release that of his wife, and his sister had to gently pull it out of the dead woman’s clasp. And then Luit died, his head resting on the bed next to his wife’s hand. It seemed almost as if he had waited on the birth before stopping to breathe.

*****

Adam was shaken awake by Tante Ellen as he burrowed deep underneath his blankets. He was dreaming of red apples and yellow pudding and had no wish to be roused. But Tante Ellen’s voice intruded, pushing away the food.

“Adam,” she whispered urgently, “Adam, you must dress quickly and …”

He was half-asleep and did not comprehend the fact that Tante Ellen’s words were hoarse and that the voice which called him from the pleasures of longed-for food was weeping. But then he was awake as suddenly as if someone had turned on a light switch.

“Why?” he questioned, rubbing his eyes.

There was another sound besides the sound of her voice – a sound that he did not recognize. Through sleep-blurred eyes he could make out Tante Ellen’s form dimly in the semi-darkness of the room. She had set a candle on the dresser next to his bed and was holding something in her arms. That something was making the unfamiliar noise.

“This is Nora,” Tante Ellen iterated, repeating in a strange, thin voice, “This is Nora.”

He sat up, the blanket falling off him, and stared. The chill air brought out goose bumps on his arms. “Nora?”

“Tante Nelleke’s baby was born a little while ago,” his mother went on, “and we must find someone who will feed her or she will…”

She stopped and the little bundle moved – moved tiny arms convulsively as if they were striking out at the world.

“Can’t Tante Nelleke…” Adam stuttered and then his thoughts halted. He instinctively felt that something was very wrong, that Tante Ellen would not be here with the baby unless, unless… “What about Oom Luit?” he whispered.

Tante Ellen stared at him for a long moment and then shook her head – shook it slowly before she spoke again. “You must dress, Adam, and dress quickly and warmly. I know that Coen Jansen’s wife had a child a few days ago. Her child died. Perhaps she will still have some milk…?”

Ellen Adriaan suddenly sat down on the edge of the bed. There was something dreadful in her eyes which frightened Adam. He pushed back the covers all the way and swung his feet over the edge of the bed. The cold of the tiled floor woke him thoroughly. He was dressed in a minimum of time and then, as if possessed by some inner knowledge, bent over and took the child from his Tante’s arms.

“It’s all right. I will take the baby to the Jansen farm.”

He left his Tante sitting on the bed and walked down the hallway cradling Nora with one hand and carrying a flashlight with the other. She stared up at him, eyes dark and large in the tiny face. He made it to the kitchen and laid the child on the table while he put on his coat and boots. He then took his uncle’s greatcoat off the rack and carefully wrapped the baby in it. Next he loosely tied a scarf around her tiny face. Picking up both the child and the flashlight, he softly opened the outside door, stepping into the night. There was a curfew, but he could detect no movement, no people anywhere. Sheltering Nora’s body against his chest and shining the flashlight onto the road ahead of him, he bent his head and began the trek towards the Jansen farm. He reckoned that it would take him a good three-quarters of an hour.

“Please Lord,” he prayed as he walked along the snow-encrusted ground, “help me find the way. Help me and Nora.”

He was not a praying child. All the Adriaans were just barely nominal Christians. Lux, Adam’s father, had taught his son very little with regard to faith or hope. He had rarely, if ever, taken him to church. But the words invoking God fell from Adam’s lips as if someone had breathed them into his throat and had pushed them out, and the boy did not know where they had come from.

*****

A gander honked somewhere in the barn when Adam finally reached the front yard of the Jansen farm. He was cold to the marrow and fearful that the baby might have died. Her face, even underneath the woolen scarf, had acquired a bluish hue and the dark eyes had closed. The transparent lids had an unearthly quality but they opened at the sound of the consistent honking. Her eyes peeped up at Adam and as she peeped up, she let out a tiny wail of distress.

He whispered down to her, overcome with a powerful emotion that had been growing in him as they walked along the road, “Shh, little one, shh! We’re here. Don’t cry!”

She stopped whimpering at the sound of his voice, crinkling her face before sighing deeply. He smiled though the action hurt him. The cold had so cruelly bitten into his cheeks, forehead and lips, that he felt any more movement might shatter his face.

“Who’s out there?”

Adam was standing by the side door. He had been here before, asking for milk for Tante Nelleke. Vrouw Jansen was one farmer’s wife who had always been kind. Perhaps she would be kind now, even though the hour was late and his request passing strange.

“It’s Adam,” he answered in a low voice, “Adam Adriaan.”

“What do you want at this hour, boy?” The voice was not unfriendly.

“I need some help.”

There was a stumbling sort of noise and a moment later the door opened and Coen Jansen’s face studied him in the dark. “What do you need help with?”

Adam did not have to answer. Nora mewled, kicking within the greatcoat. Coen Jansen stared as he stood in the doorway in his longjohns. Then he bent over and peered down into the confines of the coat. “You have a baby in there?”

“Yes.”

“Your Tante Nelleke’s baby?”

“Yes.”

“Is she…?”

“Yes.”

“Come in, boy.” Coen Jansen led Adam into the warm kitchen, opened the stove, threw a piece of wood onto the smoldering fire of its pot-belly, and stirred with a poker. “Sit down,” he commanded before walking out into the hall, and Adam sank into a chair, holding Nora close and feeling exhausted. She was now making sounds, insistent sounds, and he drew back the scarf, regarding her intently.

“You have to make a good impression,” he whispered, “so smile if you can.”

Farmer Jansen strode back into the kitchen. “My wife will be here in a moment,” he remarked rather gruffly, “she wants to see the baby. What is it’s name? Is it a boy or a girl?”

“A girl,” Adam answered, “and her name is Nora.”

Coen Jansen sat down opposite Adam. His eyes were kind. “Here,” he said suddenly, “give me the child. You are frozen through. Stand next to the stove, lad. Warm yourself.”

Adam stood up, handed him the baby and positioned himself next to the stove. From there he watched the farmer gingerly unwrap Nora from the heavy greatcoat that had been Oom Luit’s. “She is a tiny thing,” was all the farmer said just as his wife walked in.

Hanneke Jansen was clad in a blue, cotton nightgown, and seemed rather frail with hair falling down her shoulders in two long, brown braids. Thirty-something, she looked younger, much younger. Her husband regarded her with a half-smile from his position in the chair, then shifted his gaze down to Nora.

“Here is your salvation, little one. Here is one who is able to feed you.”

Step by step Hanneke Jansen inched towards her husband. Adam watched intently, momentarily forgetting that he was cold, hungry and tired.

“Her breasts are bursting with milk,” Coen Jansen went on, still speaking to Nora but now eyeing his wife, “and the Lord has this day provided food for your little lips, food that will leave you satisfied.”

A sob escaped from Hanneke Jansen’s heart. “Do you think so, Coen?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said, and handed her the small bundle that was Nora as he spoke.

She took the baby from his arms and stood quietly, holding Nora without moving. From his place by the stove Adam could see that Nora’s eyes were solemnly fixed on Vrouw Jansen.

“I will feed her,” the woman finally said to no one in particular, “if she will take my milk.”

“Ah,” answered her husband, “and is this milk yours?”

She did not answer but turned and left the kitchen, dandling Nora in her arms as she walked out.

“Would you like some bread, Adam?” farmer Jansen asked.

Startled Adam nodded. “Thank you.”

Coen Jansen got up, speaking as he rose. “You must not mind that my wife did not speak to you. She is still weak from losing our child three days ago. We lost two before that… Yet… if she’d had proper care,… but no one was here at the time but myself… and so…”

He left sentences dangling. Whether he spoke to the boy or to himself was not obvious. Adam nodded sagely, but farmer Jansen was not looking at him but busy opening a breadbox as he was speaking and taking out a loaf of bread. The boy left off nodding and stared. He’d not seen a loaf of bread for as long as he could remember. When Coen Jansen placed a plate with two thick slices in front of him, his hands trembled with eagerness to bring the food to his mouth. The first bite was pure joy and he chewed slowly and carefully for he wanted the moment to last and last. There was nothing at all in the whole world, he knew with great certainly, that he desired more than this particular mouthful of bread. Farmer Jansen watched him.

“You haven’t eaten for a while, have you?”

Adam, did not answer until he had swallowed that first bite. “No,” he shook his head as he answered, simultaneously letting his hands tear off another small piece. The knowledge that he could chew and swallow all of the bread on the plate in front of him was exquisite.

“How would you like to work for me for a while, Adam?”

Adam’s hand, which was lifted halfway to his mouth, stopped short. “Work for you?”

“Yes. Work. Work such as clean out the stalls, sweep, and what have you.”

“And Nora?”

“Well, she is too small to be working,” Coen Jansen joked, “but I’m fairly certain that my wife is going to want to keep her for a while.”

And the thread of fabric weaving both Adam’s and Nora’s life, pulled tighter now, pulled tighter into what was the beginning of a straight line.

*****

Ellen Adriaan had no objections whatsoever to her nephew staying and working at the farm, especially when he occasionally brought home some food. As for Nora remaining with Hanneke Jansen, she shrugged indifferently.

“I cannot feed her,” she said, “and with Luit and Nelleke gone, she is better off somewhere else.”

Each time he came home Adam dutifully reported on the progress Nora was making. But Tante Ellen never appeared to be listening and neither did she ask questions. Nor did she put forth any effort to see her niece, somehow irrationally blaming the little girl for the deaths of her brother and sister-in-law. Eventually Adam stopped talking about Nora when he came home. But it was really not a home for him any longer because Mikkel Ganzeveer had moved in and married Tante Ellen as soon as was decently possible after the double funeral.

*****

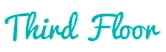

Then the war was almost over. In the spring of 1945, April 29, to be exact, RAF aircraft took off from England to take part in the first of several missions to drop food on the starving people of Holland. This operation, which was referred to as “Operation Manna” was explained to Adam by Coen Jansen as they cleaned out the barn together.

“Do you know which Bible story speaks about bread called manna dropping down from heaven for God’s people?” he asked the boy.

Adam shook his head. He was not too familiar with any Bible stories, although he was becoming more acquainted with some of them as Coen and Hanneke Jansen faithfully read the Bible out loud after each meal. Adam liked listening and thought a great deal about what he heard. Had the manna been wrapped in paper and put in packages – packages like the planes dropped? He knew that the Allied planes flew at very low levels for the food drop-offs because the amount of silk required to make parachutes for the parcels was not available. The planes simply opened their bomb doors and free-dropped the food over designated areas. Thousands of people saw the food parcels drop. They were supposed to watch from the safety of their homes, from behind their windows. This they had been instructed to do by the authorities. But tremendously excited at the prospect of food and regardless of the orders, many people ran outdoors to see the food dropped firsthand and they cheered for the airplanes from their places in the streets and in the fields. Adam thought about the Dutch people’s disobedience to the authorities and he superimposed it on the story of the Israelites and their journey through the desert. Coen Jansen had recounted the story to him several times now and he believed everything Coen told him for he had begun to love the man who continued to be most kind to himself and to Nora. Adam wondered if the Israelites had scanned the heavens for food and speculated whether or not they had been overcome with excitement as multiple packages descended on them – packages containing bread and meat. Coen had actually not mentioned whether the Israelites had been allowed to watch and to cheer. Or whether they had only been allowed to peek out from behind tent flaps.

Adam went on to consider whether or not God had also been personally responsible for the food parcels that had landed in the cities of Leiden, the Hague, Rotterdam, and Gouda. Surely if God had sent manna to hungry people in the desert, He could also have sent food to people in Holland. After eating the gifted food, the Israelite people had not been very grateful, if Adam understood the matter correctly, and things had not ended well for all of them. Should he, therefore, thank God for these packages dropped by the air force? – packages of dried eggs and milk, beans, meat and chocolate? Just in case? He distinctly remembered his heartfelt prayer to God on the night he had taken Nora over to the Jansen’s. God had heard that prayer. Or would he have gotten to the farm safely anyway without the prayer? Life was full of questions. Overriding all of them, however, was the fact that he was happy at the Jansen farm; that he was thankful that his little cousin Nora was thriving; and that he did not miss Tante Ellen in the least.

After the war, neither Adam nor Nora moved back to live with Ellen Adriaan, who was now Ellen Ganzeveer. Mikkel Ganzeveer had carefully pointed out to his new bride that the advantages the children would receive by staying on at the farm overrode the disadvantages that would arise should they come back. He smoothly asserted that the Jansens appeared to be happy with Adam and Nora. With no children of their own, it would be cruel to take them away. Besides that, food was still in short supply and Adam and Nora now had access to both food and fresh country air. There was logic in what Mikkel said and the truth was that Ellen wanted nothing more than to put a great distance between herself and that which had taken place during the war. Adam was part of that. His surname was Adriaan, a name spit upon by many local people, and a name Ellen wanted erased from her past and her memory. And so the children stayed on at the Jansen farm.

*****

At the end of the summer, at the onset of the school year, Coen Jansen sent Adam, who had turned ten in August, to the local school, a Christian school.

“School will be good for you,” he said to the boy, “you have to learn many things if you ever want to run a farm of your own.” He added softly, “and that is what I would want a son of mine to do – to go to school and do his best.”

Adam had nodded solemnly and obediently. He had always liked learning and had a quick mind. Punctual and cheerful in the farm chores Coen assigned to him, he also faithfully watched out for his little niece whom he loved devotedly. Ever mindful of the promise he had made to his Oom Luit, he played with Nora, sang to her and often rocked her to sleep. The only crack in Adam’s existence was that he did not get on with the grade five teacher.

Mr. Legaal was a middle-aged man, short of stature, temper and patience. He knew, as most of the townsfolk did, that Adam’s father had been a collaborator. But Mr. Legaal, unlike most people, held it personally against the boy. Not a single child in the classroom blamed him for that. Behind hands it was whispered that Mr. Legaal’s oldest son had been killed in a Nazi raid in which Adam’s father was suspected to have been involved.

*****

There were Bible lessons each day. Mr. Legaal paced back and forth in front of the class flicking a wooden ruler against the side of his right leg as he told stories from Scripture. He was a good storyteller. Every now and then he stopped to ask questions. He often singled out Adam and Adam knew this was because he usually did not know the answer to the questions and was thus made to look foolish.

“Who was the first man, Adam?”

“Adam was the first man.”

All the children were aware of Mr. Legaal’s prejudice against Adam and they had, for the most part, taken the teacher’s side. After all, who hadn’t hated the Nazis?

“What happened to Adam?”

“He… he fell into sin.” Unfamiliar with Biblical phraseology, Adam was hesitant. To fall was to trip, to slip. You slipped on the stairs, you slipped in ill-fitting shoes and you fell on the ground. Was sin in the ground? But he knew from past experience, even as these thoughts passed through his mind, that this was the answer Mr. Legaal was looking for.

“What is your name, Adam?”

“My name is Adam, sir.”

“Have you fallen into sin as well?”

From where he was standing in the aisle, Adam looked down at his desk. He peered into the deep, black recess of his inkwell. You always had to stand up when speaking to the teacher. He knew Mr. Legaal expected him to answer yes, but he did not totally understand why the answer should be yes. So he did not answer. Mr. Legaal walked down the aisle and stopped in front of him, his ever-present ruler mechanically slapping the side of his grey trousers. He went on speaking. “Often those who sin do not repent of their sin. Do you know what happens to those who do not repent of sin, Adam?”

Adam could feel his cheeks flush but he still did not answer, concentrating his gaze on the ink well. You could write good things with black ink. How curious was that? The boy in the desk behind him snickered.

”I think that any student in this room could easily give the answer to this question, Adam. Those who do not repent go to hell.”

The ruler stopped tapping the pant leg and Mr. Legaal turned around, away from Adam, to stride back towards the front of the class. “I think it would be good for you to reflect on the judgment of God, Adam. I want you to stay after school and copy a Bible passage I have marked out for you.”

Adam sighed. Hanneke Jansen, or Tante Hanneke as she wanted to be called, would once more be waiting in vain by the school playground with Nora sitting in the stroller. And he would not be in time to help Coen in the barn.

*****

The text which Mr. Legaal deposited in front of Adam in clear, concise handwriting, and which he had to copy twenty-five times, read: “For I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me.”

As Mr. Legaal sat at his desk correcting work, Adam mechanically wrote out the words, wrote them out over and over. A jealous God? Of what was He jealous? And how did one visit iniquity? He used to visit Tante Ellen regularly, but she had never been happy to see him. He missed his Oom Luit. Oom Luit had been a good man – a man he would have followed had he been a soldier. Adam’s thoughts scratched about in his head even as the nib of his pen scratched the paper. There was really no one now to whom, or with whom, he belonged. There was Nora, of course. She crawled after him and overtop of him on the kitchen linoleum when he played with her after supper each night. And Coen and “Tante Hanneke,” he grimaced as he addressed her this way in his head, had never given him cause to doubt their affection for him. It was just that “Tante Hanneke” sounded a lot like Tante Nelleke. Tante Nelleke was not there anymore either and she had truly loved him. Coen Jansen had told Adam that he would be pleased to be on a first-name basis with him.

Adam smudged the word “fathers,” the ink making a dark spot. He sighed. Mr. Legaal would be sure to comment that he had been careless and there was no doubt but that he would tell him he must write it out again. Consequently he added a twenty-sixth line to the second page of his remedial homework.

“Are you ready yet, boy?”

“Yes, sir.” He stood up and trudged up the aisle, his footsteps sounding awkward and hollow in the empty classroom. Laying the papers on the desk in front of his teacher, he waited.

“You’ve blotched a word here, Adam.”

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Legaal slid the papers across the desk back to the lad.

“Write it out one more time.”

“I already did, sir. You can count it out. There are twenty-six lines on the sheets.”

“Read the text for me, Adam.”

And Adam read: “For I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me.”

“Do you think your father hated God, Adam?”

“I don’t know, sir.”

“You don’t know?”

“No, sir. He never spoke of it.”

“Hatred or love comes out in what we do, Adam. Do you not know what your father did?” Mr. Legaal’s voice was even and unemotional, but his eyes, cool and grey, contemplated Adam with disdain.

And Adam remembered with a certain amount of pain in his stomach, that his father had never spoken to him of anything that he did or did not do; that his father had never included him in any conversation; that his father had only had conversations with him when ordering him to do something such as “Get me a drink” or “Clean up the dishes.” Only Oom Luit and Tante Nelleke had been kind. But now they were both gone.

“He…,” the boy faltered, seeing the demanding face of his father metamorphose into that of Mr. Legaal, “my father… he went out and I don’t know what he did.”

Mr. Legaal smirked, “Fine father he was.”

Adam looked down at the floor.

“You may go, boy.”

And Adam went.

*****

Coen and Hanneke did not ask why Adam had to stay late or why he had to write lines. The truth was that they guessed things were not very easy for Adam at school but they hoped that time would show his classmates that the boy was earnest, well-behaved and kind. And Adam told no one his problems but the gander that Coen kept in the barnyard. It was a wild greylag and Coen had successfully domesticated it as a sort of guard dog.

“Geese,” he had told Adam, “have a loud call and are sensitive to unusual movements. He’ll let me know if anyone or anything comes on the property. That’s how I knew you were there the first night you came to us.”

“Really?” Adam had asked rather doubtfully, eyeing the proud animal as it waddled around the yard, orange beak lifted up as if it owned the world, adding hopefully, “Wouldn’t you like a dog to do that for you?”

“Tante Hanneke doesn’t want a dog,” Coen answered, “A dog sat on her once when she was little and she just doesn’t want one.”

“Oh,” Adam answered, a trifle disappointed.

But for some reason Hugo, the gander, took a grand liking to Adam. It sought him out when the boy crossed the farmyard and inexplicably followed him from place to place. The bird even tolerated Adam’s hand as he stroked the greyish-brown plumage, often emitting loud honks if the boy sang songs he had learned in school.

“I think Hugo either feels you have bad taste in music or he thinks you are a gander too,” Coen joked.

“He won’t migrate, will he?” Adam asked.

“No, I’ve clipped his wings. He’ll stay the winter.”

It was late fall, moving towards winter and Adam had seen large flocks pass overhead as they flew southward. Their flight calls, a loud series of repeated deep honking, was audible for miles and Hugo’s brown eyes, it seemed to Adam, were forlorn at such times. “Does he want to go?”

“I think not. He has it far too good here. His own small pond, lots of feed, and he has you.”

“Will you ever get a female goose for him?”

“Perhaps next year,” Coen said, “Who knows?”

*****

As the days edged towards Christmas, there were advent sermons on Sundays. Usually Adam went along to one of the two services in the church which Tante Hanneke and Coen attended. He did not understand much of the sermons, but liked sitting in the bench with Coen, sharing a peppermint or two, and feeling a sense of peace. But if someone had asked him, he would not have been able to put this feeling into words.

The other service he babysat Nora, and Coen went to church with Tante Hanneke. Nora was growing, almost walking, and her favorite word, much to Adam’s delight, was “Adah.” The child was beautiful and resembled Nelleke. Black ringlets framed an oval face; huge, blue eyes sparkled underneath curling eyelashes; and two dimples appeared whenever she laughed, which was often. Tante Hanneke, Coen and Adam all doted on her.

*****

Late one evening, Adam woke up with a great thirst and got up to get a drink of water. Passing Tante Hanneke’s and Coen’s bedroom, he could not help but overhear.

“We have to take steps for adoption.”

It was Tante Hannek’s voice and Coen’s reply, in a lower timber, was almost impossible to discern. Adam shuffled on in his slippers, towards the kitchen. Adoption, what was adoption? He looked it up in the classroom dictionary the next day and read: “Adoption: formal legal process to adopt a child.’ He went up the page to the word “adopt” and read: “to raise a child of other biological parents as if it were your own, in accordance with formal legal procedure.”

During the ensuing school hours Adam thought much about the adoption definition and what it could mean – thought so much that Mr. Legaal gave him lines. “I must not daydream” was copied fifty times during recess. But when he sludged home that day through the thin, wet skiff of snow that lay on the ground, he continued to wonder – to wonder if Tante Hanneke had been speaking about Nora or about himself, or about both of them. It would make more sense if her words had referred to Nora. Nora was, after all, only a baby and she didn’t know any better but that it was Coen and Tante Hanneke who were her parents. She was already calling Tante Hanneke “mama” and Adam found that he did not mind that in the least. It was clear to him that Tante Ellen did not want Nora. Neither did she want him. Not that he minded. Tante Ellen made him increasingly uncomfortable by totally ignoring him when he saw her.

He slid on the snow. Geese flew overhead. He stared up at them. Geese were free. He had read once that geese mated for life. Loyalty seemed a beautiful thing to Adam. Hugo, if he ever got a mate, would stay true. Geese were loyal. He’d reached the farmyard now and Hugo, silhouetted against the barn door, honked and waddled over towards him.

*****

That evening Coen Jansen began reading the Gospel of Matthew after the meal. Nora sleepily hung back in her highchair, eyes half-closed. It was warm in the kitchen. Adam yawned behind his hand. He scanned the room and remembered the first time he’d sat down in the leather chair next to the stove. He could see himself sitting there even as Coen was reading the genealogy – names and names and more names. Adam saw the names floating around in the air as if they were music notes. All these names must have had faces at some point – faces and lives.

“… the father of Jehoshaphat, and Jehoshaphat…”

What a strange name that was. His mother must have had some time calling him in for chores. “Jehoshaphat! Come here!”

“… the father of Jeconiah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon.”

“What’s deportation, Coen?” Adam knew he was allowed to interrupt to ask questions. Coen had made that very clear at the onset of his stay here.

“Deportation is,” Coen began, furrows lining his brow as he formulated the answer, “being sent away from where you live.”

“Oh,” Adam responded, “you mean that I was deported from Tante Ellen’s house.” He noted that Tante Hanneke threw Coen a look. The look was almost angry.

“No,” she said, “No, it’s not like that at all.”

Adam appeared slightly puzzled and she went on a bit irrationally – went on as color rose in her cheeks. “Well, you weren’t sent away from your home. You must not think of it like that. You just have to remember that we really wanted you to stay with us. The deported people Coen was reading about were disobedient and God punished them by sending them away. You were not …” She stopped abruptly and smiled at him before she added, “Do you see?”

“Yes,” Adam replied, although he did not really see, but he told himself that he would think about it. Coen went on reading, after exchanging another look with his wife. “And after the deportation to Babylon, Jeconiah…”

Nora began to whine. Tante Hanneke lifted her up out of the highchair and settled the child on her lap. Thumb in her mouth, Nora smiled a drooly smile at Adam. He grinned back.

“… and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary of whom Jesus was born…”

Jesus, that was the Son of God. Jesus, that was in whose name Coen always prayed and was teaching him, Adam to pray. “You must say ‘for Jesus sake’, Adam, at the end of every prayer.” So he did. It was enough for him that Coen said so. Coen never lied.

“… Now the birth of Jesus Christ took place in this way. When His mother Mary had been betrothed…”

“What’s betrothed, Coen?”

“Betrothed is like being engaged. You know that time when a boy gives a ring to a girl because he wants her to be his wife.”

“You have to give a ring to a girl if you want to marry her?”

Coen and Tante Hanneke smiled simultaneously. “Well,” Coen said, “that’s usually what’s done.”

“Did Tante Ellen get a ring from Mikkel Ganzeveer?”

“Probably,” was all Tante Hanneke would answer.

“When his mother Mary,” Coen repeated, turning back to the Bible, “had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child of the Holy Spirit, and her husband Joseph, being a just man and unwilling to put her to shame, resolved to divorce her quietly.”

“Where did the child come from?”

There was no answer for a few moments. There was only the crackling of the wood in the stove and the wet sound of Nora noisily sucking her thumb.

“The Child,” Coen began, “that is to say, Jesus, came from heaven.”

“You said,” Adam interposed, “that heaven is a good place. You said last night that it was better than any place on earth.”

“Yes,” Coen nodded, “that’s true.”

“Well, then,” Adam went on, “why did Jesus leave it?”

“He left it so that you and I could go to it.”

Adam’s face was blank and Coen continued. “Well, we can’t go to heaven if we are dirty, that is to say, sinful. Remember that we talked about sin the other day? God can’t abide sinfulness. So Jesus left heaven to make us clean. He became a human being like you and I; He lived the perfect life that you and I could not live.”

They were just so many words to Adam. He understood that he did bad things. He knew that deep within himself he was not good. He didn’t know why this knowledge was in him, but it was. Falling into sin, that’s what Mr. Legaal had spoken of in the classroom. But for Adam the discussions were more or less like falling into a sea of words and drowning in their meaning without being able to come up for air. It was too much.

“Why didn’t God just make our sins go away,” he responded, “Wouldn’t that be easier than leaving heaven, and besides that, He can do anything, can’t He?”

“Yes, He can,” Tante Hanneke came into the conversation, “but He chose to do it this way. The Bible tells us that He took on our flesh. The Word, that is Jesus, became flesh and lived among us. We have seen His glory… I think,” she added thoughtfully, “that because Jesus became a baby, and grew into a child, who grew into man, Who died for us, we can see Him more clearly as one of us, and we are impelled to follow Him.”

“Impelled?”

“Well, that means we have to. We just can’t help it.”

“Become like us?” Adam said, “But why would He want to come to a place like our town where so many people…”

He didn’t finish. He never divulged the painful moments at school; never spoke of the secret kicks, the snide remarks, and the multiple snubs that were his daily fare. Coen closed the Bible.

“If He hadn’t come to earth,” Tante Hanneke repeated, patting Nora on the back, “the disciples wouldn’t have seen Him, and then they wouldn’t have been able to tell us about Him, and then we would not have been able to follow Him.”

“But why couldn’t we have followed Him without Him coming here?”

Coen cleared his throat, preparing to answer, but no words came out

“I wouldn’t have come to earth if I were Jesus,” Adam finished, “and that’s the truth.” Suddenly embarrassed that he had said too much, he shrugged and stared at Nora, pulling a silly face. Nora took the thumb out of her mouth and laughed out loud, dimples showing. Then she began to cry and Tante Hanneke motioned that Coen should finish off by praying, it was time for bed.

*****

A few days later, on a Sunday afternoon walk through the woods with Hugo by his side, Adam noticed that someone or something, was following closely behind him. There were noises like branches breaking and it seemed that the trees overhead were whispering. He turned sharply at one point, only to see two boys run to hide behind a bush.

He stood still for a minute but they did not come out and he resumed his walk at a quicker pace. Hugo, trotting in and out of the bushes, picked up speed as well. Then a rock hit the back of Adam’s head just above the nape of his neck. It hurt and he did not know if he should stop, stay his ground and have it out with his pursuers, or keep on walking. If he stayed, the boys might hurt Hugo. On the other hand, Hugo was a good fighter. He had seen the gander hiss and snarl and spread his wings at the goat when the animal had playfully butted too close for Hugo’s comfort. It began to snow, and Hugo, unaware of any danger, honked his contentment. He delighted in cold weather. Adam reached his right hand up to gingerly touch his head where he could begin to feel the swelling of a bruise.

“Hurt you, did we boy?” It was the voice of Herman, a boy in his class. Adam recognized it. He decided to stop and turned around.

Herman was not alone. Kees Legaal, the son of Mr. Legaal, was with him. Kees was also in Adam’s class. There was a rock in Kees’ hand and in a swinging motion he lifted it above his head, making as if to throw it. Hugo had halted as well. The bird, sensing the tension in Adam, suddenly stood up straight next to the boy, puffing out his chest, and spreading his wings.

“Hey, look at that dumb goose.”

“It’s a gander,” Adam replied, “and he’s not dumb.”

“Oh, no? Well, watch him fall down.” Kees threw his rock, but the missile went awry as Hugo simultaneously streaked towards the boys, hissing in a frightful manner. Reaching them, he began to peck and bite, going for legs, arms and bellies. For a moment Adam was transfixed with pride. Hugo was protecting him.

Then he called out: “Hugo. It’s all right. Hugo, come home with me.”

The gander, after a few more seconds of nipping sharply at his prey, stood still. His frightened quarry turned tail and ran. Kees ran helter-skelter down the road but Herman disappeared to the left.

The left turn was a mistake. Crashing through several layers of bushes, not watching where he was going, he ran headlong into Zonnemeer, a small but deep pond covered with a thickening but treacherous coating of ice. Adam could hear Herman falling; could hear the sound of ice cracking; and then he heard the sound of water splashing, water swallowing. Next to him, Hugo was nibbling on some snow, looking remarkably unconcerned and innocent. Losing no time, Adam followed the boy’s trail, until he reached the edge of the pond. Herman’s head was visible where he had fallen through in the ice and his eyes looked shocked and scared. There were several feet of unbroken ice between the edge of the pond and the spot where he had fallen through. Although Adam’s first instinct was to run out onto the ice to help, he was extremely conscious of the treacherous instability of the surface of the pond.

“It’s all right, Herman,” he shouted, “stay calm.”

The boy began to cry and Adam prayed, and he prayed out loud, “Please God, let me help Herman so that he will be all right, for Jesus sake.”

A calmness came over him.

“Lift your elbows out of the water,” he said clearly, remembering what Coen had told him to do should he ever fall into one of the many ponds in the area, “and rest them on the edge of the ice where you fell in, and breathe in deeply and slowly.”

He took off his woolen scarf, a red one that Tante Hanneke had knit for him, and measured it. It was a long scarf and would perhaps do the trick if he would be able to get just a little closer to Herman. He gingerly stepped out onto the ice. It held him and appeared solid. Herman never took his eyes off Adam even as Adam tied a loop at the end of the scarf. Perhaps if Herman’s hands were too cold to hold the scarf, he could put the loop around his elbows. Prepared to throw the red rescue line, he heard the snow behind him crunch. It was Kees who had come back to see what happened to his friend. Panicking upon seeing him in the pond, he stood rooted at the edge.

“Herman,” he shouted, “don’t drown.”

“If you want to help,” Adam said, “hold my hand while I throw the scarf out to him.”

Kees nodded and slid onto the ice behind Adam. Adam held out his left hand and Kees took it. The whole scene felt surreal to Adam, almost as if he were dreaming. And perhaps, he reasoned within himself, he was dreaming and in a few moments would wake up in his bed at the Jansen farm. But Hugo honked from the pond’s edge, and he supposed that such a loud honking would never take place in a dream. He felt Kees’ stiffen at the approach of the gander.

“It’s all right,” he reassured the boy, “Hugo won’t hurt you. He’s just watching to see what I’m doing.”

Kees didn’t answer. He merely nodded and shivered. Adam carefully took aim and threw the scarf across the ice towards Herman. Herman had closed his eyes now.

“Herman,” Adam called out, “open your eyes and try to get hold of the scarf. We’re going to try and pull you out of the water.”

Herman opened his eyes and slowly reached for the scarf with his right hand.

“That’s it,” Adam shouted encouragingly, “reach just a bit further. You almost have it.”

Herman seemed to be moving in slow motion. His hand was almost on top of the scarf and then his fingers took hold of the wool. Clamping down on the red, his other arm rose out of the water and followed the first.

“Good,” Adam called out, and Kees joined him, “That’s good Herman. You can do it. Grab it with both hands.”

Herman managed the feat and both of his hands were now wrapped up in the wool.

“I’m going to pull slowly but will need both my arms,” Adam cautioned Kees, “so let go of my hand but hold on to my coat.”

Kees did as Adam instructed him and Adam began to strain as hard as he could. At first, there was no movement although Herman’s arms were now flat on the ice in front of him grasping the scarf. But then his body began to shift upward. Slowly the boy emerged from the water. His eyes were closed again. As soon as his belly slid onto the ice, Adam was able to step back.

“Here,” he said to Kees, “help me pull now. You can let go of my coat and grab the scarf. Pull as hard as you can. We’ll get him out together.”

All this time Hugo was waddling back and forth on the land behind them, honking fiercely every few minutes. Kees took hold of the scarf as well, and began to lend his weight to the taut line. And bit by bit Herman was drawn closer, and drawn onto the shore. His clothing was sopped through and through. Adam took off his own coat and undid the buttons on Herman’s coat.

“Help me, Kees,” he said, “Help me take his coat off and then we have to get him to walk, or run, so he doesn’t …”

“I know,” Kees responded, and knelt down beside his friend. Together they managed to take off the boy’s coat and get Adam’s coat wrapped around him.

“Stand up, Herman,” Adam said, “You have to walk now. I know you feel tired but you have to walk.” He slapped Herman’s face. The boy opened his eyes.

“I’m so cold,” he whispered.

“I know,” Kees answered, “and soon we’ll be home and we’ll get you totally warm by the stove. But you have to get up and start walking or…”

To their surprise, Herman sat up and attempted to rise. Kees and Adam both put hands under his armpits and helped him up.

“Good,” Adam said, “very good work, Herman. Now walk with us.” Herman obeyed – obeyed as if he were a robot – and the three began their trek back to the village.

“My house is closest,” Kees said after they had been walking for some five minutes which seemed like five hundred, “so we should stop there. I’m afraid…”

*****

They reached Kees’ house after another ten minutes walking. Herman had ceased to talk. He just mechanically moved his legs forward. His eyes were shut again. Kees ran up to the front door and yelled for his father. Adam had both arms wrapped around Herman who was leaning heavily against him. Mr. Legaal appeared in the door. His eyes took in the situation and he immediately told Kees to start warming hot water bottles, as well as call for his mother to get some hot drink ready. Meanwhile he ran outside on his stocking feet, positioned himself on the other side of Herman and helped guide him towards the door, towards the warmth of the house. Mr. Legaal said nothing to Adam during this time and Adam spoke no word to him. Hugo was still on the road, honking dejectedly.

When they got to the door, Mr. Legaal finally broke the silence between them. “You can go now,” he said to Adam, “I’ll take care of Herman.”

And Adam, after a final look at Herman who was still wearing his coat, went.

*****

The wind had picked up in force and miniscule ice pellets fell. It would be Christmas on Wednesday. Adam loved the songs that Tante Hanneke hummed as she prepared meals and as she went about the house. He also loved the songs he was learning in school. To take his mind off the stinging ice that hit his face, he tried to sing one after leaving Mr. Legaal’s house.

But his voice would not obey his thoughts. His hands were numb and reaching for the pockets of his coat, remembered that he was not wearing a coat. He stamped his feet as he walked. Hugo had half-flown, half-waddled ahead of him down the road. He was trailing his right wing but seemed set on going home quickly. Adam watched him until the bird disappeared around a bend. There was a loneliness settling within him. It was like the frost that had cruelly nipped at his cheeks the night he had carried Nora, only this cold was tugging and nipping at his heart. The Jansen farm was ahead and he was glad of it for he did not think he could keep walking much longer. Tante Hanneke would ask where his coat was and what would he say? He had begun to shiver and although he tried very hard not to shiver he could not help the uncontrollable shakes that seized him every few seconds. If he could just sit by the stove for a bit, just for ten minutes or so, with no one speaking to him, it seemed to him that he would be all right. The door was in front of him and he stared at it, unable to reach for the handle.

“Adam.” It was Coen’s voice and it came from behind him. He moved his head to see where exactly Coen was, but then everything went dark and he slid down, down into a pond of treacherous ice, blackness and night.

*****

When Adam opened his eyes, he was lying in bed and Tante Hanneke was sitting in a chair by his side. She was knitting, knitting something red – perhaps another scarf? He closed his eyes again and wiggled his toes in delicious warmth. How good it was to be wrapped up within a house, within a bed and to have someone sitting by your side who loved you. He reopened his eyes and this time Tante Hanneke stopped her knitting and laid it down in her lap.

“You’re awake, Adam?”

He smiled a weak smile in agreement.

“That’s good. You had me very worried for a while. You have quite a lump on the back of your head. Where have you been?”

There was no reproach in her voice. It was just a question. He smiled again trying to remember where he had been. He vaguely recalled the walk with Hugo by his side. And there were boys – Herman and Kees. And there was the pond. He closed his eyes and sighed. “I was,” he began, and to his own surprise, he could not continue, but started to weep.

Tante Hanneke laid her knitting on the floor and sat on the edge of the bed. She took his hands in her own and rubbed them gently. “Never mind,” she said, “it doesn’t matter. What matters is that you are home safely and that I love you.”

“I’m home,” Adam whispered, and then he fell asleep again.

*****

When he awoke for the second time, it was because there was noise of some sort in the hallway. There were voices. He recognized the voices but could not put a name on them. A minute later the door to his bedroom opened and Tante Hanneke walked in. She was followed by Mr. Legaal who was followed by Coen. They all looked serious. Adam wished he could put his head under the covers, but his whole body felt paralyzed. Tante Hanneke smiled reassuringly at him, and sat down on the edge of the bed.

“You have a visitor, Adam.” She spoke the words even as she took hold of his right hand.

“Hello, Adam.” Mr. Legaal mouthed his greeting in a clipped manner, and Adam half expected him to produce a ruler and begin hitting his leg with it. He did not answer. His mind might have woken up but his voice was still sleeping and unwilling to awaken.

“I came over,” Mr. Legaal went on, “to tell you that I’m very thankful you brought Herman to my house this afternoon. It was a good thing you did, Adam.”

Behind his teacher’s frame, Adam could see Coen smiling cheerfully. But his own mouth would not smile back.

“You know, Adam,” and Mr. Legaal’s voice became rather low, as if he was having trouble enunciating words, “I made you copy out lines at the beginning of the school year, lines from Deuteronomy five.”

Tante Hanneke raised her eyebrows and looked at Coen, who shrugged behind Mr. Legaal’s shoulders.

“The words were,” Mr. Legaal hoarsely went on, “For I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generation of those who hate Me.”

Both of Tante Hanneke’s hands now enclosed Adam’s right hand and she sighed.

“But,” the teacher continued, as his eyes now fully met Adam’s, “I neglected the second part of that text which reads, ‘but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love Me and keep My commandments.'” It was very quiet in the bedroom. Adam could hear his own heartbeat and felt it pulse in his temples. “You are one of the thousands, Adam, and I am sorry if I …”

Mr. Legaal turned sharply, almost bumped into Coen and, passing him, made his departure.

Coen cleared his throat. Tante Hanneke cleared hers as well.

“Your teacher,” Coen began, “told me what happened this afternoon, Adam.”

Adam nodded. He was weary and actually wanted to go to sleep again. But he did wonder if Hugo had come home. He did not remember seeing the bird in the farmyard when he came back from his walk. But then there were a number of things in his head that were fuzzy.

“Hugo?” he asked.

“His right wing is a bit sprained. I’ve put him in a pen by himself for a few days. He’s fine though, or will be in a day or two, and he is as bossy as ever.” Adam smiled and drifted off again.

*****

Though he was pampered for the next few days, Tante Hanneke did not judge him quite well enough to go to the special Christmas Eve service. He protested, albeit weakly, that she should not worry and that he felt up to the walk, but she would not hear of it.

“It looks like snow,” she said, “and I want you to stay nice and warm inside. And that’s an order.”

“I don’t want you to miss the special service for me,” he said, “so I’ll stay home only if you go to church.”

Coen had nodded in agreement. “Adam is right, Hanneke,” he said, “He’s well enough to watch Nora and the two of us can go together.”

Tante Hanneke had not truly wanted to leave him, but she had conceded the battle. Dressed warmly the two of them had left for church after supper.

*****

It had begun to snow ever so lightly. After he put Nora to bed, Adam stood by the kitchen window and watched the flakes dance. They illumined briefly as they swirled past the glow of the lantern swinging from the front porch. It was fascinating and for a long while Adam felt unable to take his eyes away. Then the flurries grew thicker and the wind picked up, faintly howling through the trees. Adam shivered, pulled the curtains shut and sat down in Coen’s big chair. How different things were now as compared to last year. He could see himself standing in front of the stove, could see Coen take the baby from his arms, and he could see Tante Hanneke walk through the kitchen door in her nightgown, braids hanging over her shoulders. And now he lived here – now this was his home. Yawning contentedly, he leaned back and closed his eyes. There was only the one thing, just one thing, which worried him now. And that was the concern he saw reflected in Tante Hanneke’s eyes when he prayed at night.

“Do you believe, Adam,” she had asked him but the day before yesterday, the day that Mr. Legaal had come, and the day that he had been so tired and despondent, “that Jesus came down from heaven to save you?” There had been a pleading in her brown eyes, and he had been tempted to say, “Of course I do.” But he was unable to bring the words forward for they were not in his heart.

So he had answered her with “I can’t,” only to see a sadness diffuse her eyes. He added, trying once more to explain his dilemma, “I don’t know why Jesus would come here and become human. Why would He want to be like us? Why would He have to do that if He truly is God?”

She had replied, as she had done before, “Because He loves us. Because He knew that we would follow Him more easily if He became one of us. ”

Then she turned away but he could hear her softly murmuring, “The Word became flesh and made His dwelling among us, full of grace and truth. We have seen His glory, the glory of the One and Only, Who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

It was a verse Adam had memorized in school this last month, but had not quite understood. He opened his eyes again. He wished that God would knock at the door and explain it to him. He wished the answer would come to him in the lantern light with the snowflakes. Nora half-whimpered in her bedroom and he got up. But when he reached the crib, she was sleeping, thumb in her mouth, curls askew on the sheet. He gazed at her for a long time, remembering his promise to Oom Luit. Stroking her cheek, he caught himself humming a Bach melody – a melody which Tante Hanneke called a Christmas lullaby.

“O Savior sweet, O Savior mild, Who came to earth a little child…” Adam felt confused by the words. He stopped humming and tip-toed out, making his way back to the chair.

As he settled in, pulling his sock-feet up and snuggling against the leather side, there was a loud thump against the window. Then another. Instinctively he slid out of the chair and lay flat on the ground. It was a reflex movement, a movement left over from the war. There were more sounds outside, but they were not the sounds of airplanes overhead, sounds he still heard in bad dreams. Slowly sitting up, he crawled over to the window on his knees. Past the curtain’s edge the yard was veiled in white and barely visible. The snowfall had become much heavier. Through the periodic gusting, his eyes met a very strange sight. A number of geese were wandering around the pathway leading to the door. Then squalls of white obliterated them from his sight.

Adam rubbed the windowpane, trying to see more clearly. Where would these geese have come from? Had they been on their way south and been disoriented by this sudden storm? He spotted two of them close to the window, flapping their wings rather wildly and aimlessly. They were running around in circles. He wished Coen and Tante Hanneke were home but, because of the weather, maybe it would be very late before they would be back. Should he go outside and help the birds? He rubbed the pane again and strained his eyes. Between the paroxysms of the wind coughing the snow past the window, Adam thought he could count at least seven geese. Was Hugo with them? No, Coen had put Hugo in a pen. Perhaps if he opened the barn door, the birds might go in and find shelter instead of flying about in such a haphazard fashion.

Before venturing outside, Adam went to the bread board and cut off several slices of bread. He doubted whether scattering the bread would make the birds follow him, but just in case… Carefully dividing the bread into small pieces, he stuffed them inside his pants pocket. Then thinking for a moment, he went to his bedroom and took the flashlight out of the drawer next to his bed. Then he walked back to the kitchen, put on his coat, his red scarf, his boots and then his mittens. Listening intently for a moment to satisfy himself as to whether or not Nora was still asleep, he stepped into the hallway and opened the door to the yard.

Honkings and hissings swirled with the wind and whirled about with the snow. Quickly stepping outside, he closed the door behind him. Oh, to be Hugo for a moment and convey to these birds in goose language that they could follow him!

Treading out a path on the snow with his boots, he dropped bread pieces and made his way to the barn. Would they follow? Initially, it seemed not. Then one of them picked at a piece of bread and nosed forward for another. But the next moment a particularly heavy blast of wind blew him and a number of bread crumbs out of Adam’s sight and when he could see again, the bird had wandered off in a different direction. Reaching the barn, he opened the door and turned on the flashlight, shining it into the doorway. Not one bird in the entire gaggle paid any attention. He walked back into the middle of the group.

“Follow me,” he pleaded, “there’s lots of straw and I can give you some chicken feed too.”

Although honkings and flappings encircled him, none of the geese even came close to his outstretched hands. They were wary of him and afraid. He was not one of them.

“Perhaps if I carry Hugo outside,” he spoke to himself, “they might follow him. After all, he is a real goose and I’m not.”

Trudging back to the barn, it took him a few minutes to locate the spot where Coen had placed Hugo’s pen. The gander sat quietly, brown eyes wide open, watching him. Adam felt a pang of conscience that he had not come to see him earlier. “Hello, Hugo,” he said, “how are you?”

The bird honked softly.

“I’d like you to do me a favor,” Adam went on, “There are a lot of geese outside, lost in the snow. I thought you might show them the way to the barn because you, after all, Hugo, are a goose just like them and they will follow you.”

He opened the pen door and Hugo waddled out, making straight for the open barn door.

“That’s it, Hugo,” Adam encouraged, “That’s it. You’re doing fine!!”

Hugo turned for one second at the door, dark brown eyes shining, his right wing hanging limply by his side. Then he turned his grey head and walked on, disappearing into the white. Adam ran after him, and reaching the barn opening, initially could see nothing but heaving snow. Then something half-flew, half-darted perilously close past his head into the barn. It was Hugo, fan-shaped tail dragging wearily behind him. Following Hugo’s lead while honking wildly and flying in a straight line, the seven geese streaked past him as well.

Turning on his flashlight, he stared at the grey birds, some of whom were already tucking their beaks under their wings. Bulky bodies, thick long necks and greyish-brown plumage were all huddled together on some straw. Hugo had retreated back into his pen. His orange bill emitted a soft “Gaa,” and Adam smiled. He heard the wind blowing outside. He did not know where it had come from or where it was going.

Illustrations are by Keturah Wilkinson.