A Christian Response to Physician-Assisted Death

by Ewan C. Goligher

2024 / 145 pages

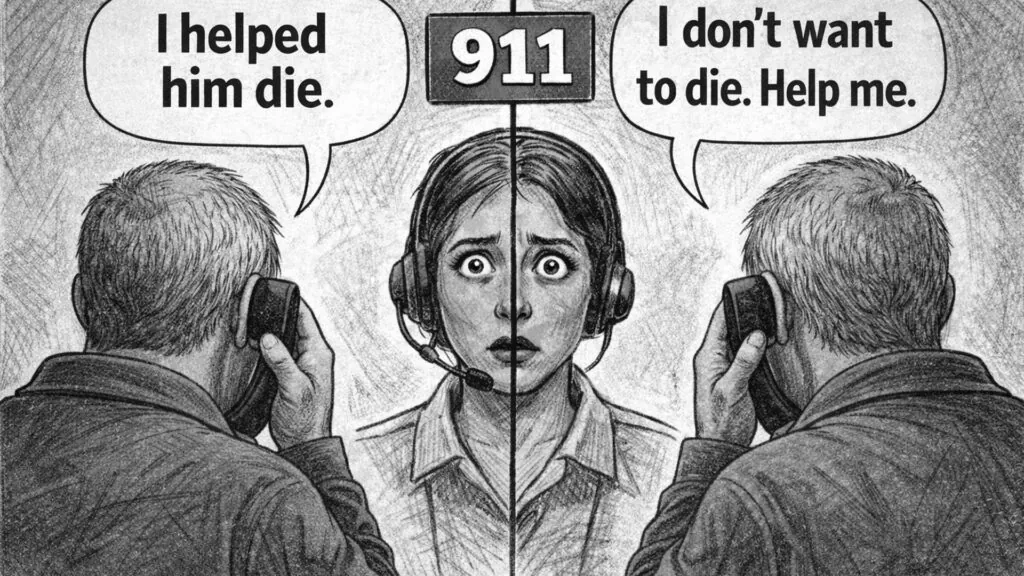

In April 2024, a desperate father in Calgary, Alberta begged a judge to prevent the doctor-assisted suicide of his 27-year-old autistic daughter. The father argued that his daughter’s “condition, to the extent that she has a condition, is mental not physical in nature” and raised serious concerns about the approval process for her death, including whether legal safeguards had been met and whether “doctor shopping” had taken place (where patients assessed as “ineligible” continue to seek out opinions from other doctors until they find ones willing to approve of their assisted suicide).

Confusion reigns

But the judge felt he could not intervene:

“MAiD assessments are conducted in accordance with the structure imposed by the Criminal Code … but they remain medical assessments conducted by doctors … [Such assessments] are private in nature and involve the application of specialized professional judgment. … The Court has no expertise and no place in reviewing MAiD assessments in some sort of ad hoc system of pre-authorization…”

But by this logic, any medical assessment, including a mistaken or careless one, approving of an assisted death could be impervious to judicial review. Furthermore, the judge reasoned that preventing the daughter from accessing “medical assistance in dying” would do more harm to her than allowing it, a deeply religious argument Dr. Goligher tackles head-on in his book, as we will see. Thankfully, the Alberta Court of Appeal granted an injunction halting the assisted death from proceeding at least until the appeal is heard later this year.

This story emphasizes just how far we’ve come in Canada with euthanasia and assisted suicide (collectively referred to in Canada with the euphemism “medical assistance in dying” or “MAiD”).

What’s more, many Christians seem genuinely confused about how to deal with the issue. I’ve taught multiple university courses on law, human rights, and public policy in two different Christian post-secondary institutions, and in most of them the issue of euthanasia has been discussed and studied. In each class, I have found Christian students who either (1) believe that euthanasia is wrong but are unable to articulate why, or (2) believe it is wrong (morally wrong, I suppose) to “impose” on others one’s belief that euthanasia is wrong.

Much-needed book

And so, not even a decade into this legal and moral quagmire, Christians in Canada are in desperate need of resources to help respond to this issue in a way that is compassionate, thoughtful, and theologically grounded. Thank the Lord for providing such a resource through the pen of Dr. Ewan Goligher!

Dr. Goligher is a medical doctor and an elder in a PCA church in Toronto. I first met him when he and I co-taught at the Christian Legal Institute (the only Christian legal training academy in Canada) and he urged students to pay careful attention to this issue and to champion the human rights of the vulnerable whose lives are placed at risk in the name of “autonomy” and “self-determination.” He also encouraged students to be prepared to defend Christian and other doctors who are clinically, ethically, and conscientiously opposed to participating in the intentional termination of patients’ lives. Since that first meeting, I’ve enjoyed a friendship with Ewan and we have picked up our conversations at other events: Christian legal and medical conferences and at the Apologetics Canada conference where Dr. Goligher has also lectured.

Ewan’s book is a beautifully written apologetic for the Christian answer to the ultimate question that every human will face: how should we then die?

Secular god doesn’t value life

Our culture is increasingly promoting one answer: “Autonomy is lord. And so I have the right to die, with public assistance, at the time and place and in the manner of my own choosing.” Ewan dispels that approach as a falsehood that completely undermines the value of some.

“So when we say that people matter, we are also saying that it is good that they exist. If people have intrinsic value, then it is always good that they exist. And if we insist that they really matter – that they have deep intrinsic, inherent value – then the cessation of their existence (their death) must always be regarded as a terrible tragedy.”

Ewan also shows persuasively how embracing “assisted death is an act of secular faith” and just how presuppositional and religious the arguments for assisted suicide are.

“Because those who claim that death is nothing don’t really know that for sure, physician-assisted death is best considered an act of blind faith on their part. It is an act at least as superstitious and religious as any carried out in any religious services of any kind. Those who administer physician assisted death are functioning not as doctors but as priests, helping their patients by ushering them out of life and into the afterlife, the great unknown.”

The real God offers real hope

But what of despair? Ewan offers a fuller, hopeful approach to those struggling to find meaning in their suffering, rooting his answer in the confession of faith as expressed in the Heidelberg Catechism: we belong not to ourselves but to a faithful, loving Savior.

Expanding on and moving beyond the work of Jewish psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, Ewan shows that, to live with suffering we need transcendent meaning rather than self-invented meaning, and that,

“we only clearly behold the true meaning and significance of our lives in the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ.”

A third way

The opening paragraph of the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2015 Carter v. Canada decision – which led to the legalization of doctor-hastened death – presented an “either/or” dichotomy: either a person dies a horrific death with extensive suffering, or they take their own life early.

However, Dr. Goligher shows his readers a third way: physical and existential suffering can be substantially mitigated without eliminating the sufferer. He also helpfully distinguishes between refusing treatment, the cessation of which leads to death, which is ethical; and euthanasia, which is not. This area of medical ethics has been the source of some confusion due to the conflation of certain concepts and terms. In short, to refuse treatment is permissible for a Christian because where there is a

“decision to withdraw life support (which is not really an action but rather the cessation of action)… the actual cause of death is the underlying illness. Life-sustaining treatments are not discontinued in order to bring about the patient’s death; rather, they are discontinued because it is recognized that they are no longer effective or appropriate.”

But any act the intention of which is to end the life of the patient is something different in kind, and is immoral because it intentionally seeks to end the life of the patient. Such action is properly called homicide. In fact, assisted suicide (or MAiD as it is called in the Criminal Code) is still classified as homicide in the Criminal Code. As Dr. Goligher notes, “The intention, or goal, of the action is the key distinguishing feature.”

Highly recommended

Ewan’s book is thoughtful and engaging. Multiple references and allusions to Shakespeare and Schaeffer, Augustine and Tolstoy, Camus and Nietzsche show a breadth of knowledge and engagement with key thinkers, without ever coming across as stuffy or academic. I highly recommend this book for young Christians’ study groups, for elders and pastors, for moms and dads, for nurses and doctors. At a relatively short 145 pages, the book is a very accessible read, easily understandable for a grade 11 or 12 student.

And it is written to be understandable and compelling to both Christians and the broader Canadian public. It presents the gospel beautifully in its final chapters.

Throughout the book, Ewan’s approach is that of a compassionate doctor, one who has clearly seen more than his fair share of suffering. Each chapter opens with a true heart-wrenching story of extreme anguish. There is no downplaying how brutal human suffering can be, but Ewan’s extensive clinical experience in managing and mitigating pain and suffering also shines through in this book. Ewan is more than a physician; he is also a pastor-elder and his compassion comes through the pages of this book too. The moving stories he shares put a lump in my throat as I read them.

As the story I opened with illustrates, and as many experiences will confirm, physician-hastened death will impose itself on the Church on many fronts. Christian physicians, nurses, and palliative institutions are being pressured to provide and approve of euthanasia (these professionals are no longer seen as virtuous but as villainous for not “supporting” their patients). Some doctors are now proactively suggesting euthanasia to elderly or disabled patients as a “medical option” that should be considered. And our culture is planting the seed early in the minds of our children (and our seniors!) to see medically hastened death as a dignified way to die. The Church cannot be silent or ignorant on this issue. No better resource is available to assist her to understand and speak than this book.

André Schutten is Senior Legal Counsel and Director of Training & Development at Christian Legal Fellowship (CLF), Canada’s Christian legal ministry. Christian Legal Fellowship sits at the intersection of the church, the state, the legal academy, and the legal profession. To learn more, please contact André at [email protected].