Science - General

Topsy-turvy world of bats

People have a love/hate relationship with bats. While these animals are interesting and exciting to some, the more common response is very negative, to say the least! This sharp difference of opinion also occurred in my husband’s family. When he was thirteen or fourteen, he worked in the summers harvesting tomatoes in market gardens in southern Ontario. The appropriate strategy, he says, is to feel for the ripe tomatoes as well as to visually examine suitable specimens. Thus at each plant he reached from below into the foliage, feeling the bottom of each tomato. The soft ones he picked; the hard ones were left for another day. On this particular occasion he happened to feel something warm and fuzzy among the tomatoes. Further research showed that it was a snoozing bat. Since he was interested in all natural phenomena, he promptly placed the bat in his lunch bucket, shut the lid, and forgot about the incident. Once home, he placed the lunch bucket on the kitchen table. The story stops with his mother’s discovery of the bat in the lunch bucket. You can well imagine the scene. She might enjoy nature too, but not this kind of nature and not in the kitchen!

If bats were prettier to look at, we might appreciate their amazing talents more. The fact is, bats exhibit some astonishing design features that our engineers and technologists greatly envy.

Three types

Traditionally, scientists have grouped bats according to their food preferences. There are:

1) fruit bats with good eyesight

2) insect-consuming, echolocating bats

3) vampire or blood-consuming bats

Further research has revealed how amazingly these animals are designed for their lifestyles. Such studies have also revealed that the old-fashioned ways of categorizing the creatures, according to lifestyle and physical appearance, do not really work. This has had some serious implications for ideas concerning whether Darwinian evolution could ever arrive at a plausible explanation for bats.

Heat-seeking vampires

The vampire bats all live in the new world (the Americas). There are only three species, each quite different. These ugly-looking creatures need blood meals to live. That means they must find a blood vessel in a victim that will allow blood to flow freely. This is not the easiest of tasks (as some nurses will attest), but vampire bats have a special design feature that allows them to find good blood sources. In their upper lip and modified noseleaf, they have special nerve endings that are much more sensitive than most nerves to body heat. These special tissues in the face allow them to find hot spots on the bodies of their victims. These hot spots are caused by blood vessels located close to the surface. The bat nips the skin with his teeth in order to drink the flowing blood.

The whole situation is horrifying to us, but this ability of vampire bats to sense elevated body heat clearly is an interesting design feature. We may not like what the vampire bats do, but how they do it exhibits great finesse.

Apparently only some snakes and vampire bats have this ability to detect infrared radiation (heat). However, the bats do it very differently from the pit vipers, pythons and boas. Snakes, for their part, make use of receptors on nerves that normally respond to chemical irritants or cold. In the case of these snakes, however, these receptors instead respond to the body heat of victims.

Now many animals have heat receptors all over the body. These receptors are designed to respond to heat that is dangerous to the health of the creature (we can sense the heat of a fire, for example). Vampire bats also have these normal heat receptors. However, in some nerves in the face of vampire bats, the nerves instead respond to a heat source which is much lower – about 30 degrees C.

The ability by bats to detect infrared radiation (heat) is so different from in snakes, that evolutionary scientists consider that there is no connection between the two designs. Either each appeared as a spontaneous or novel feature, however complicated, or each was separately designed in its entirety.

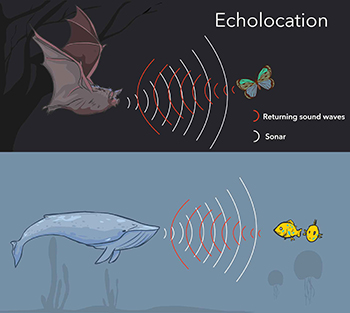

Echolocation is a marvel

But it is the engineering triumph of echolocation (like sonar) that really commands our attention and awe. This system is complex, with many features that must work together precisely. The bat must produce powerful ultrasonic signals which will bounce off objects and travel back as echoes. The creature must know the mathematic characteristics of the sound emitted in order to be able to compare it with the echo. The echo will be much softer, so the creature must be able to hear the incoming signal. Often the tempo of sounds emitted will include intervals between notes so that the incoming echoes can be heard. The bat must be able to judge its own position and speed relative to the returning echo which indicates the position and speed of the target object. This ability requires special mathematical programs in the brain to calculate the differences in speed and constantly changing location.

But it is the engineering triumph of echolocation (like sonar) that really commands our attention and awe. This system is complex, with many features that must work together precisely. The bat must produce powerful ultrasonic signals which will bounce off objects and travel back as echoes. The creature must know the mathematic characteristics of the sound emitted in order to be able to compare it with the echo. The echo will be much softer, so the creature must be able to hear the incoming signal. Often the tempo of sounds emitted will include intervals between notes so that the incoming echoes can be heard. The bat must be able to judge its own position and speed relative to the returning echo which indicates the position and speed of the target object. This ability requires special mathematical programs in the brain to calculate the differences in speed and constantly changing location.

Although the requirements for the system are so fancy, there still is lots of room for variation in details. Some bats use a constant frequency (narrow band or single tone), while others use many more tones for frequency modulated (broadband) emissions. The tempo of the sounds can vary with the species and differences in intensity (from 120 decibels at 10 cm to 80 decibels at 10 cm) are possible. Many bats make sounds with their larynx, but one species uses tongue clicks. One might imagine that so fancy a sonar system would be found only in a closely related cluster of organisms, if descent with modification (evolution) had taken place. However, we see similar fancy systems in whales, bats, shrews, tenrecs (hedgehog like mammal native to Madagascar) as well as in oilbirds and cave swiftlets (another bird). Obviously, these creatures did not descend from a closely related common ancestor, so either these organisms were designed, or spontaneous processes produced these fancy systems on a number of occasions.

As far as the bats themselves are concerned, one might imagine that the echolocating bats would represent a cluster of creatures with other features in common. Even when the echolocating system is similar however, there are bats which seem closer in their genetics to the fruit bats. In addition, one fruit bat echolocates by means of tongue clicks instead of noise from the larynx. Does this represent a separate group too?

Bats are cousins to… cows?

Altogether, bats represent a fascinating example of evolution theory gone wrong. During the past century for example, scientists considered that bats were related to organisms like lemurs which display similar arm bones used for flight. Such anatomical similarities to lemurs, caused scientists to classify bats with monkeys, flying lemurs and rodents. Then, however, on the basis of more obscure biochemical details which come from the genetic code, bats were grouped with horses, dogs, cows, moles and dolphins. The physical and behavioral similarities to these latter creatures are obscure to say the least. Nevertheless, scientists said this latter group is evolutionarily related through descent from a common ancestor.

Altogether, bats represent a fascinating example of evolution theory gone wrong. During the past century for example, scientists considered that bats were related to organisms like lemurs which display similar arm bones used for flight. Such anatomical similarities to lemurs, caused scientists to classify bats with monkeys, flying lemurs and rodents. Then, however, on the basis of more obscure biochemical details which come from the genetic code, bats were grouped with horses, dogs, cows, moles and dolphins. The physical and behavioral similarities to these latter creatures are obscure to say the least. Nevertheless, scientists said this latter group is evolutionarily related through descent from a common ancestor.

When one considers echolocation, scientists now declare that this complex capability arose spontaneously at least seven or eight times. And the ability to detect infrared radiation arose scientists now declare, twice independently in snakes and once independently in bats. Scientists use the word convergence to cover situations where descent with modification is not a convincing explanation for the source of the feature. Thus convergence means separate appearance of the same abilities, for no obvious cause. It was not convincing when the argument was for the spontaneous appearance of a complex system on one occasion, but to suggest that it could happen multiple times really strains credulity!

The alternative explanation for these situations of course is separate designs. God used his tool kit of wonderful design features as he saw fit, conferring them on similar or very different creatures for our interest and delight. What these amazing designs really demonstrate is the action of a mind, creative intelligence, and choice.

Only scratching the surface!

So far we have barely scratched the surface of the wonderful design features in bats. Recently scientists have discovered that the ability of bats to sense their environment is even more sensitive than previously imagined.

In 2010, a team of scientists reported that some echolocating bats can control the width of the ultrasonic beam which they emit. The subject of this study involved bats that release sounds from their larynx, which is by far the most common method.

More recently, another team investigated whether the tongue clicking Egyptian fruit bats are similarly versatile in their ability to respond to variation in the environment. This team found that Egyptian fruit bats simultaneously direct one beam of sound to the left and another to the right. They do this by aiming consecutive clicks in opposite directions. As the environment becomes more cluttered with objects, the angle between the two beams of sound becomes wider (and the beam thus broader). This enables the animal to focus on a particular object while paying less attention to other distracting structures in the environment. Also as the bat closes in on his target, the beam becomes broader and the sound more intense. This degree of sophistication in this echolocating system is a surprise to everyone.

One interesting other characteristic of bats is their wonderful wings. Bats can carry up to 50% of their weight (as we see in pregnant bats) and they execute maneuvers that would cause a bird or plane to crash.

One interesting other characteristic of bats is their wonderful wings. Bats can carry up to 50% of their weight (as we see in pregnant bats) and they execute maneuvers that would cause a bird or plane to crash.

Unlike birds, bats have wings that are thin and flexible. This is the result of more than 20 independent joints in the structure covered by a thin flexible membrane. Bats can curve their wings too, thereby providing for greater lift which consumes less energy.

What is more, bat wings are covered with tiny sensory hairs that provide information to the bat on flight speed and air flow. As one commentator on bats remarked: “The perceptual world of bats undoubtedly has many more intriguing secrets yet to be discovered” (Nature August 4/11 p. 41).

The large number of precision machines or systems in bats which enable them to live challenging lifestyles, surely proclaims the work of God, the creator of all things. We may still not love these interesting creatures, but we can certainly regard them with sympathetic respect. Probably however no amount of talking will make bats welcome in the home!

A version of this article was published in the December 2011 issue