An aquarium-based science experiment for the whole family

*****

Summer is here and there are any number of projects in which the whole family can participate. Of course, some are more fun that others – painting the fence, for example, will not rank high on anyone’s list. This is especially so if the junior members of the establishment spill the paint, or elect to decorate the family car with it.

However, almost everyone enjoys splashing about in water, so why not consider an expedition to a pond in your area to start off your own family aquarium? Be warned: some individuals may get a little wet while chasing aquatic insects with a bucket or net. And dad may have to venture the farthest out to catch some particularly elusive creature. But children, just remember that if you want the project to be a happy experience, don’t push your Daddy into the pond! If anyone gets pneumonia, the project will definitely not be judged a success!

Step 1 – set up the aquarium

The first thing to do is acquire an aquarium. It doesn’t need to be too big, and you can probably find something used on Kijiji or Craigslist for $50.

The aquarium should be placed in a window where it will receive moderate light, or it should be equipped with a fluorescent light. Place about an inch of gravel in the bottom – soil works too, but it is messier.

Next some structure should be provided in the form of a few larger stones, a rock, sea shells, or pieces of waterlogged wood. Don’t overdo the structure. Only a small proportion of the volume and at most a quarter of the bottom area should be occupied by solid objects. These are important because they provide hiding places for various animals and surfaces on which to grow. Living aquatic plants also provide structure.

Several inches of water may then be added. City water contains chlorine, which isn’t good for our aquatic life so if you are using it, be sure to leave it out to sit for several days to allow the chlorine to escape. Once living creatures are in the aquarium, then any new city tap water you add (to make up for whatever evaporates) must be boiled and thoroughly cooled first, in order to remove the chlorine.

Step 2 – just add life!

The aquarium is now ready for the addition of pond water with its contained organisms. The objective is to set up a self-perpetuating ecosystem (physical environment with its contained living creatures).

Ideally all you will need to add once the system is established is water and light. Plants use the light to combine water, dissolved carbon dioxide, and mineral nutrients into food for the rest of the organisms in the aquarium. Moreover, plants in the light release oxygen into the water. This is essential if the aquatic animals are to stay healthy.

Gathering your aquatic animals is a particularly fun part.

Before setting out for the pond, make sure that mom and dad and all the offspring are equipped with rubber boots and buckets or large jars all with tops. Scoop nets are optional. The best procedure is to fill the bucket with pond water and some submerged pond weeds. You will acquire many pond creatures simply by collecting water and weeds. A few small pieces of decaying vegetation are good to collect too. These will have other organisms growing on them and, besides the dead material will provide for scavengers.

However, don’t collect very much of this “nonvigorous” (i.e. decaying) plant material because too much decay will result in all the oxygen being used up. And without oxygen many animals will die and soon the whole aquarium will smell “swampy,” releasing hydrogen sulfide gas and methane into the atmosphere. At this point some mothers might banish the whole system right out of the house!

Step 3 – let’s find out what we have

Once the aquarium is filled with water and pond weeds, then you and your children can peer into the water to discover what you have collected. Some creatures last only a few days, others last almost indefinitely.

Among the animals in your fresh water ecosystem, some will be easy to see, others hard to see because they are small or because they hide. Some will be so small they’ll only be visible with a microscope. While all have fascinating life stories we will discuss only easy-to-see animals. Here are your possible cast of characters.

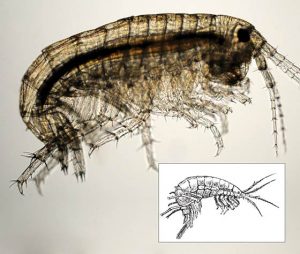

Gammarus

In our family the favorite pond inhabitants are the amphipods or scuds known by the Latin name Gammarus. These delightful creatures do well in an aquarium. They swim through the water in a conspicuous way so that it is easy to show doubters that indeed there are animals present.

Gammarus look much like marine shrimp. Their bodies are protected by a hard exterior skeleton or surface made of chitin. That is a hard, not easily decomposed material like our hair and fingernails. The body is divided into numerous sections and each segment bears a pair of legs. There are five different kinds of legs. Some have gills attached. The legs are used for swimming, for grasping food, and for obtaining adequate oxygen.

These animals swoop through shallow water in semicircular arcs. They feed on bacteria, algae, and decaying plant and animal material. Mostly they confine their activities to within 20 cm of the bottom sediments. When collected in the summer Gammarus are at most one-and-one-half centimeters long. They continue to grow, however, as long as they live. By March, Gammarus which were collected the previous summer are three cm long (approximately twice as long as their maximum size in nature). Few will survive beyond April. Outside, in the Canadian climate, they would have died with the frosts of the fall.

I add small pieces of boiled and cooled lettuce to the aquarium when the food supply for Gammarus seems low. If these “shrimp” are observed swimming round and round the aquarium, it is a safe bet that they are short of food. They seem to have a chemical sense for detecting food. When lettuce is placed into the water, they circle closer and closer. One individual may find the lettuce within seconds, eight or more within three minutes.

As far as reproduction is concerned, in nature this proceeds throughout the summer. Both sexes are found in the population. The females carry their eggs and developing young in a brood pouch. The young resemble adults in miniature. One or two young have appeared in our aquarium during the winter months.

Water fleas

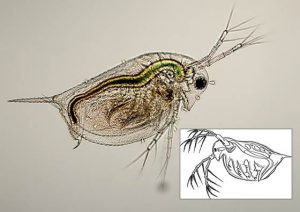

Most likely your aquarium will harbor water fleas as tiny as they are numerous. The white specks which move in jerky fashion through the water, are most probably Daphnia. You might even catch a species bigger than the tiny ones which presently populate our aquarium. The largest species of all can be found in very productive waters like the Delta Marsh of Manitoba. It boasts individuals as large as the fingernail on a lady’s fifth finger. All water fleas are crustaceans, as are Gammarus. They have an exterior skeleton of chitin and numerous jointed legs. Water fleas are an important source of food for aquatic insects, larger crustaceans, and various fish.

Each Daphnia has a small head from which extend a pair of branched antennae. By moving these projections like oars, the animal is able to make awkward progress through the water. Five pairs of legs are attached to the body, but they do not show, nor are they used for swimming. Like the rest of the body except for the head, they are enclosed in a convex shell which is hinged along the back and opens along the front. Constantly moving within their confined space, the legs create a current of water which brings in oxygen to bathe the body surface and also a stream of food particles. The numerous hairs on the legs filter out the food particles and push them forward to the mouth.

During most of the growing season only females can be found in the Daphnia population. Like dandelions which reproduce without benefit of sex, so water fleas also reproduce by parthenogenesis. Females produce eggs which do not need to be fertilized. These develop directly into more females. A pond can fill up with females in a very short time! The number of eggs per clutch varies from two to forty, depending on the species. The eggs are deposited within the female’s body into a brood chamber or cavity under the protective shell on the animal’s back. The eggs develop there and hatch to look like miniature adults. They remain within the pouch under the shell until the female molts, shedding her external skeleton and shell. Then the young are released.

As conditions in the pond become unfavorable through drought, cold weather, or decline in food supply, fewer parthenogenetic eggs are produced. Now some eggs, by a mechanism which is poorly understood, develop into males! Other eggs at this stage require fertilization in order to develop. The brood pouch around eggs which have been fertilized, now thickens into a saddle-shaped structure called an ephippium. These are released to sit through long periods of drought or freezing. Ephippia can be transported from pond to pond in the intestines of aquatic birds or simply by clinging to their wet feet. When favorable conditions return, ephippia hatch exclusively into parthenogenetic females.

Plants

Perhaps we should turn our attention to some suitable pond plants as well. The duckweeds are the easiest to identify. Exceedingly widespread, lesser duckweed (Lemna minor) is common in quiet ponds. Often these tiny leaves will form a mat over an entire pond. In these circumstances hardly any plant life grows below the water surface because the duckweed has intercepted almost all the light. In an aquarium this species does not grow well unless it has very bright light available. Dying leaves are quickly eaten by snails and Gammarus. Another species, ivy duckweed (Lemna trisculca), is much more suitable for aquaria. The leaves grow in T-shaped configurations which remain tangled in large clumps below the water surface. It does very well with moderate light and it is an important oxygenating agent in the water.

Coontail and milfoil are similar plants often found floating free in tangles beneath the surface in ponds. Coontail (Ceratophyllum) is known for its densely bushy stem tips. The leaves, which occur in whorls, have tiny toothlike projections. This plant does only moderately well in aquaria. Perhaps the best that can be said is that the plants may take all winter to die and be eaten by scavengers. Milfoil (Myriophyllum) has whorled, finely divided leaves which look like fern fronds. These plants are good aerators of pond water and should do well in an aquarium.

Waterweed or Elodea is so suitable for aquarium culture that you can buy it in pet stores. More enterprising individuals may simply fish some out of a pond. The stems are bushy with whorls of three oval leaves arranged along the stem. These plants start out rooted but can become free floating. Elodea has been popular in biology laboratories for generations. Students can perform experiments on oxygen production on whole submerged plants. Individual leaves, which have only two layers of cells, are good for examination under the microscope.

A handy reference booklet, available for generations, is Pond Life (a Golden Guide) which was last updated in 2001.

USOs – Unidentified Swimming Objects

Having acquired an aquarium, pond water, and pond plants, your family may at this moment be scanning several unidentified swimming objects. Some of these may well prove to be aquatic insects.

Among the varied inhabitants of ponds, the insects provide the greatest interest for many people. All insects have an exterior skeleton much like that of crustaceans, but, whereas crustaceans have numerous legs, insects have only six.

Many insects make fresh water their home during part or all of their lives. Most, including those which spend all stages of their development in the water, have one or two pairs of wings as adults. The young of some insects have the same general build as their parents. They resemble miniature adults and differ from them only in the partial development or their wings and the lack of sexual organs. Mayflies and dragonflies produce such young called nymphs. These develop in fresh water, but the adults spend their lives in the air. Among the true bugs, of the fresh water representatives, water boatmen are the easiest to find. They live in water throughout their lives.

Many other insects have young quite unlike the adults. These young often seem quite wormlike. Such larvae must enter a resting stage, the pupa, before an adult emerges. During the pupal stage, an individual’s tissues are broken down and reassembled into those of an adult. Among such insects, caddisflies spend immature stages in the water and adult stages on land. So do certain flies including crane flies and phantom gnats. Mosquitos act the same way. Aquatic representatives among the beetles, however, spend their complete lives in or on the water. These include whirligig beetles and predaceous diving beetles often called water tigers.

Mayflies

Nymphs are typically found clinging to stems or stones in the water. Their abdomens curve upward towards the rear and the tip is equipped with three feathery tails. The abdomen sweeps continuously back and forth, perhaps to create a current in the water. In side view the numerous paired flaps down each side of the body cannot be seen. Viewed from above, however, these structures, called gills, are visible. Although the flaps are called gills, they seem not to be involved in gas exchange.

Nymphs feed on small plants, on animals, and on organic debris. They live a few months to three years in the water, depending upon the species. This fall at least one adult successfully emerged into our living room after several weeks sojourn in an aquarium. Adults have four nearly transparent wings which they hold vertically when at rest. Adults are unable to eat, and they die shortly after mating. The females lay their eggs in water.

Dragonflies

Nymphs are solid looking, flattened creatures up to 5 cm long. They do not swim much, preferring rather to wait until some suitable prey happens to pass. Then they suddenly extend a huge hinged “mask” or folding lower lip to seize the unsuspecting victim. They feed on insect larvae, worms, small crustaceans, and even small fish. They are very fierce, and I, for one, would not offer a finger to any of them. I maintained two nymphs for several months by feeding them small pieces of hamburger. They would seize the meat only as it was sinking. Often, they would fail to notice the food. In order to keep the aquarium from becoming foul due to meat decay, I usually retrieved the missing pieces (with tongs) and dropped them in a second time near the nymph.

Some dragonfly species complete their development from egg to adult in three months, while others take as long as five years. During this time, they molt frequently. At about the fifth molt, wings begin to form. Adult dragonflies have slender silhouettes and they hold their transparent wings horizontally at right angles to the body. With their legs or jaws, adults grasp insect prey such as mosquitos, and they eat them while in flight. They live only a few months, but during that stage adults mate while in flight. The female often drops her eggs from the air into the water.

Water boatmen

These adult bugs are one of the easiest insects to spot in ponds, but they do not do well in an aquarium. This is probably because they are strong fliers and can leave any body of water which they do not like. Adults appear silvery in the water since air taken at the surface surrounds them like a silvery envelope. Strong flattened hind legs enable these bugs to swim strongly. They feed on algae and decaying matter sucked out of the bottom mud. Adults lay their eggs on aquatic plants. In our aquarium, boatmen have reacted very negatively to the glassy confines of their new home. They spend their time frantically trying to swim through the glass walls. None lasted more than a day.

Caddisflies

The larvae of these insects are generally easy to identify. Only the head and front legs can be seen peeping out of tube-like cases made of green leaves, sand, twigs, or bark. Each species fashions a different characteristic house for itself. The adult emerges into the air and looks much like a moth.

Crane flies

Last fall our children spotted a revolting, pudgy-looking worm just under the water surface of our aquarium. It was the larva of a crane fly lurking among the aquatic weeds. It always positioned itself so that its rear tip projected up into the air. This creature had no legs at all. Our tentative identification proved correct when after several weeks a crane fly, like a large mosquito with long legs, appeared in our living room. Apparently, we had missed the pupa stage. Adults of some species feed on nectar, others do not eat at all. None bites.

Phantom gnats

If you peer intensely into your aquarium, you may see one or two phantom larvae. Except for prominent eyes and a threadlike intestine running the length of the body, the rest of this creature is almost transparent. The rear is capped with a tuft of obvious projecting hairs. There are no legs. These larvae, 1-2 cm long, hover horizontally well down in the water. This animal is unusual among insects in its ability to maintain such a stationary position in the water. Antennae attached to the head allow these larvae to prey on mosquito larvae and other small animals. The adults, which develop from a pupal stage, look much like mosquitos, but they do not feed and hence do not bite.

Mosquitos

Probably no aquarium is complete without several wrigglers (mosquito larvae). These bend double and extend to their full 1 cm length again as they wriggle through the water. They too lack legs. Frequently they return to hang almost vertically from the surface. A tube extending from near the rear tip is extended up into the air to get oxygen. The larvae feed on microscopic organisms or organic debris. Within a few days, after passing through a pupal stage, the adults emerge. The females must obtain a blood meal in order to be able to lay eggs. Males feed on nectar and ripe fruit. If your mother does not like mosquitos emerging into her house, do not call them to her attention. Alternatively, you could place a screen over the aquarium.

Whirligig beetles

Often the most conspicuous insects in a pond are swarms of small oval shiny black beetles darting frenetically back and forth on the surface of the water. Their eyes are divided into upper and lower parts. They are believed to be able to see both above and below the water surface at the same time. They eat anything they can find. Their front legs are long and slender, the others are shortened and flattened to serve as paddles. They can dive down into the water very suddenly if alarmed. Everyone chases these beetles, but they are difficult to catch. Anyway, they do not do well in aquaria.

Dytiscus

Among the hungriest and meanest of aquatic insects are the larvae and adult stages of the predaceous (from predator) diving beetles. The streamlined larvae, up to 3 cm long, with upturned abdomen and fierce jaws open, stand awaiting the arrival of prey. Konrad Lorenz, in his classic book King Solomon’s Ring, devotes several pages to the nasty personalities of Dytiscus larvae. These larvae will attack other insects, tadpoles, minnows, or anything that smells of animal in any way. They will bite a finger or even attack other larvae of their own kind. Through hollow jaws they inject a digestive juice which dissolves the insides of most of their victims. For people, the bite is simply extremely painful. We had several such larvae in our aquarium, but they died within several days, probably because of lack of suitable food. The shiny oval adult beetles also manage in the air and they may grow to be as large as 3-4 cm long. The beetles enjoy much the same menu as the larvae, but the former are also strong fliers when they so desire.

Other easy-to-culture animals

Both leaches and snails are easy to identify and easy to keep in an aquarium. A leach has done well all winter in our aquarium. It occasionally appears undulating through the water. It is growing, so it must be doing well eating bacteria. Certainly, it is not obtaining any blood meals. Our giant pond snails also do extremely well. With a thin, narrowly spiraled shell, these animals grow to be about 5 cm long. Often you can see the mouth opening and closing as one oozes forward along the glass. Inside the mouth is a rasping tongue which scrapes algae and bacteria off all surfaces over which it moves. Occasionally, jelly-like masses of snail eggs appear on underwater surfaces. These soon hatch into numerous tiny snails which immediately begin eating their way around the aquarium.

Keep it going

Now the whole family is organized for a project which can last all year. Remember not to load too many relatively large animals into an aquarium. The larger the total volume of animal life, the more likely it is that you will have to bubble in air and supplement the food supply. One minnow, for example, could eat everything living and require oxygen besides. This is not your objective. Stock with more, but smaller animals! Tadpoles, too, will require oxygen and will eat everything in sight.

Make it a practice to observe life in your aquatic ecosystem every day. It makes a wonderful topic for conversation at the supper table. You will have expanded your interests and your pleasure in God’s creation.