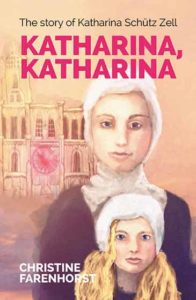

This past year we celebrated the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, and with the focus on Luther, but also other big names like Calvin, Knox and Zwingli. But there were countless others used by God and in this excerpt from Christine Farenhorst’s novel “Katharina, Katharina” (which is reviewed here) we learn of the Reformation as it happened in the city of Strasbourg, 400 miles from Wittenberg, and as it happened in the life of Katharina Schütz Zell. The following is an excerpt from chapter 23.

In the early fall of 1518, when the heat was beginning to ease off just a breath, and trees were setting up their easels of autumn colors, Matthis Zell, a new priest, took charge of the cathedral parish of St. Lawrence.

****

It was Katharina’s friend, Annalein, who first informed her that St. Lawrence had acquired a new parish priest.

“What does he look like?” Katharina asked, her curiosity piqued.

They were sequestered in the Schütz sitting room, side by side, heads drawn close in conversation. She poked Annalein, who was dreamily staring out at the rectangular-shaped windowpanes through which the afternoon sun was shining.

“What does he look like?” she repeated impatiently.

“Who?” Annalein asked, almost as if she were waking up, “Whom does who look like?”

“The new parish priest,” Katharina said, resisting an urge to shake Annalein. “You just told me that St. Lawrence had a new parish priest.”

Annalein had always been rather absent with her thoughts. But Katharina knew that there was not a kinder girl in the whole of Strasbourg.

“Oh, the new priest,” Annalein responded, a slow smile appearing at the corners of her mouth, “He seems quite nice, actually. But Katharina, you will never guess whom I saw at Mass this morning. Herr Burrman and his wife and ….”

“I didn’t ask if the new priest was nice, Annalein,” Katharina patiently replied, “but I asked what he looked like. You know as in: Was he tall? Did he have dark features….?”

“Oh,” Annalein said, “is that what you meant?”

“Yes, it was.”

“Well, I only saw him from a distance and could not make out his features very well. He was of medium height – neither short nor tall. And whether or not he had a dark complexion….”

She stopped, shrugging a little helplessly and then went on, animation lighting her pale face.

“But Herr and Frau Burrman had their son with them. He is quite tall and rather good-looking, I think. They remembered me and stopped to speak with me. The son was very kind also. He asked after my health.”

During the somewhat rapid flow of words cascading down from Annalein’s lips, Katharina observed her friend carefully. As far as she could recall, she had never heard her speak of anyone of the male gender with such praise.

“What is his name? What is the son’s name?”

“It is Reinhart.”

“Reinhart,” Katharina repeated, adding, “a very noble name.”

“Yes, indeed,” Annalein agreed, “I did think so as well.”

Katharina smiled indulgently, before adding, “So might you see him again?”

Annalein blushed most becomingly.

“Well, he did say that he might call on my Mother, just,” she added innocently, “to ask about some particular matters with regard to her tapestry work. He was thinking of buying something for the church because he is so thankful about his mother’s complete recovery.”

“Oh, I see,” Katharina said, “a devoted son. And that is,” she added, “the way it should be.”

“Indeed,” Annalein agreed demurely, hands folded in her lap, “he appears to be very devoted.”

Then the girls caught one another’s eyes and they both began to laugh – first softly, but their peals of laughter increased by the moment. It was at that moment that Katharina’s sister Margaret walked in.

“What are you laughing at?” she demanded, almost beginning to laugh herself because the merry sound that met her was so contagious.

“Oh, nothing,” Katharina spoke with difficulty, heaving a big sigh to control the mirth that kept bubbling up.

“Nothing?” Margaret said disbelievingly.

“Well, actually we were speaking of… of the new parish priest at St. Laurence,” Annalein added, trying hard to speak seriously.

“Well, what is so humorous about him?” Margaret asked, “I have heard him preach a few times and he is quite….”

She stopped. In spite of herself, Katharina was intrigued.

“He is quite what, Margaret?”

“Well, I would say, he is quite stern.”

“Stern?”

“His eyes,” Margaret said, sitting herself down on a chair opposite the two girls, “his eyes are quite piercing and when he speaks, you must listen for you cannot look away.”

“You have not spoken of him before,” Katharina observed, “but it seems that he has made quite an impression on you.”

“He carries himself,” Margaret went on, “with a quiet dignity and not at all like many of the priests we are wont to see who….”

She stopped, rather at a loss.

“Yes,” Katharina encouraged.

“I would not,” her sister said softly, “I would not malign those of the church and thus incur… incur….”

“I know,” Annalein finished her hesitating words, “you are not eager to incur a lot of disapproval, especially when you will feel bound to confess in the booth to your local priest what you have just said. For he is likely to fine you and give you a week’s worth of ‘Hail Mary’s’ to boot.”

“Annalein!”

Both of the Schütz girls gasped at her audacity. Annalein placidly stared at them.

“It is true what I said, is it not? I think I am not the only one to scoff at those who preach good works but who steal from the poor.”

As the sisters continued to stare at her, she added, “And, from what Margaret has just said, I would like to hear brother Zell preach, and not,” and here she poked Katharina in the side, “just look at him.”

It was Katharina’s turn to blush.

“I merely wanted to know what he looked like, so that I would recognize him on the pulpit,” she responded with what dignity she could muster.

“As I said, I have heard him,” Margaret repeated, noting her sister’s blush with interest, “and I do learn from what he says.”

“How old,” Katharina asked, “is he?”

“I think that he would be in his late thirties, maybe about forty years of age,” Margaret said, “quite old really. But not so old as Father. And,” she added as a non sequitur, “he has a rather large, longish nose.”

****

It was not until several of months later, not until the spring of the new year of 1519, that Katharina finally met the new pastor of St. Lawrence in person.

She had gone visit a woman whose only son, an eight-year old, had become ill with a severely swollen stomach. Steadfast at the boy’s bedside, the mother had barely had any sleep. The child’s stomach was so distended he continually screamed with pain. Purgatives had been administered, but the boy repeatedly vomited them up. Just prior to Katharina’s visit, the doctor had concocted a powder which the child had kept down, soon afterwards passing a great many worms in his stool.

“May Almighty God,” the mother whispered, “still grant His grace in letting Kristoff live.”

Katharina patted her hand, then guided her towards a small cot made up in the corner of the boy’s bedroom and made sure she lay down. Satisfied when both mother and child appeared to be sleeping, she went outside into the small yard with a bucket of sudsy water to clean the soiled sheets and blankets. She was thus occupied when she saw a priest approach the dwelling. Because she was aware that both child and mother were trying to sleep, she quickly ran to intercept the man.

“Pardon me,” she called, crying out just as he was lifting his hand to knock on the door, “but have you come to visit Frau Freiburg?”

He stopped, hand in mid-air, and nodded. Somewhat shyly, she went on to explain that she was helping the family, putting her own soapy hands which held an old towel behind her back.

“They were sleeping, both she and her child, when I left them some fifteen minutes ago,” she finished.

The priest had a rather longish nose and remembering her sister Margaret’s comment, Katharina suspected that it might be the new priest of St. Lawrence parish and bit back a smile.

“Truth be told,” she went on, as the man did not respond but simply gazed at her, “the sleep will do both mother and child a world of good as the boy has been, and still is very, ill. But you are undoubtedly aware of his illness.”

While she spoke, she dried her hands on the towel.

“So I take it,” he spoke, and his voice was a rich, deep baritone, “that you suggest I not come in.”

“Far be it from me,” she replied, “to tell you what to do. But, yes, given the severity of the boy’s affliction and that he has been but a foot from the grave, I would deem it wise that you not awaken them.”

“You are quite right,” he smiled, “and I think they have a fine neighbor in you, for you are a good Samaritan. Would that all the people in Strasbourg were so blessed.”

She blushed and he regarded her deeply for a long moment without speaking.

“My name is Matthis Zell,” he finally spoke.

“Yes,” she responded, “so I thought.”

There was another quiet.

“And what might your name be, if I may be so bold as to ask?”

“Katharina – Katharina Schütz.”

“Ah,” he responded, regarding her with his great brown eyes, eyes which reminded Katharina of a faithful dog.

She experienced a certain amount of regret that she had not worn a better gown, one with, perhaps, elaborately cuffed sleeves. But this man, this priest, did not seem the type of fellow to whom a matter such as dress would be important. Nevertheless, she felt a strange desire to appear pleasing to him, to appear neat, with a hair net hiding the ever-rambunctious hair strands that always escaped from beneath her cap.

“Well, I must….” Katharina eventually said, blushing as he chose that same moment to also speak.

They both left off words again and Katharina was quietly contemplating a return to her labors on the sheets and blankets, when they heard an agonized cry come from within the house.

“I think,” the priest said, “that we… that you, at any rate….”

Katharina lost no time and bolted past Master Matthis Zell, who stepped aside to let her enter the front door. The wailing that met their ears, as soon as the door opened, was heart-rending. Katharina ran towards the bedroom. Although she had left both the mother and the boy in slumber, a state of turmoil and disorder met her eyes when she entered the bedchamber. Frau Freiberg was attempting to hold Kristoff, her son, down. But he, talking constantly, although not in such a way that one could understand him, was frantically trying to get out of bed. His breathing was labored and difficult and his eyes were bulging. Katharina knelt down on the opposite side of the bed and attempted to help Frau Freiberg get Kristoff to lie down again. Matthis Zell stood in the doorway, but then also drew near to the bedside.

“Let me help,” he said, “I am stronger. Perhaps if I lift him up and carry him about, he will be more comfortable.”

The two women immediately stood up and Matthis bent over the child, easily lifting the lad up in his strong arms. Initially Kristoff quieted in the priest’s embrace, but just as Katharina was about to heave a sigh of relief that a crisis had been averted, the child began to convulse. Within a few minutes, the boy was dead – dead in the priest’s arms. Gently he laid the boy back on the bed, closing the wide-open eyes. Then turning to the bereft mother who had fallen down on her knees by the edge of the bed, tightly gripping the blanket in her hands as if by doing that she might hold on to the life of her little one, he laid one hand on her head.

“May God keep Kristoff safe until we come to him!”

“Indeed,” Katharina echoed, even as she, coming around the bed, put her arms about Frau Freiberg.

A little cowhide-covered horse stood in the corner of the room. Herr Freiberg, a merchant, had brought it back for Kristoff from one of his business trips the last time he had been home. A brown jerkin and some skin-colored stockings hung over the toy’s side. How long ago had it been since the boy had worn them? How long since he had played with the horse? How vain life was! Soon this child, Katharina fleetingly mused even as she patted Frau Freiberg’s shoulder, would be buried to the tune of clergy’s chanting and the sound of bells would carry his memory away. For who would remember him in the long run? Who would?

****

Later, after Frau Freiberg’s relatives had come to be with her, Katharina and the black-robed Matthis Zell went home, walking together side by side for a considerable length of streets. Katharina was somewhat lost in thought, her mind overly occupied with the loss that Frau Freiberg had to sustain. Why did such things happen? It was true, all men had to die – but such little ones?!

Hard put to keep up with Katharina’s quick steps, Matthis was uneasy. He was impressed by the girl’s gentle and yet decisive manner, by her way of helping the family they had just left, but she seemed so far-off with her thoughts now. He studied her profile as she paced next to him. It almost seemed as if she had forgotten that he was there.

“Which church,” he began in a low tone, curious but also genuinely interested in the young woman that providence had placed on his path, “do you attend, Fraulein Schütz?”

She began walking slower, suddenly realizing that he was still there, and turned her large blue eyes towards him. They were troubled, he noted.

“Which church?” she repeated slowly, “Well we, that is to say, my family and I, always attended Dr. Geiler’s church. After he died his nephew, Peter Wickram, took over the pulpit but Peter Wickram is not his equal in preaching, I am afraid.”

He inclined his head to show that he had heard this, but did not say anything else, as he believed it was in bad taste to criticize a colleague.

“You are at St. Lawrence?” Katharina asked him.

He nodded again.

“Yes, I am and I have been given comfortable quarters on the Bruderhof Strasse just behind the Cathedral.”

He did not know himself why he volunteered this information. Surely the girl was not interested in knowing where his place of residence was.

She smiled, slowing her pace even more, “I am glad for you. It must be difficult to come to live in a new place where you know very few people.”

“The ones I have come to know have been kind,” he rejoined.

“Where,” she hesitatingly went on, not wishing to appear nosy, “are you from?”

“From Kaysersberg.”

“Oh, that is where Dr. Geiler was from. It was his home town.”

Her face shone now and he remarked within himself that the smile which transformed her face exposed a sweetness that was very pleasant to behold.

“Yes, I have heard that he was.”

“And did you know,” Katharina went on eagerly, “that forty years ago Dr. Geiler was on his way to a preaching post at Wȕrzberg when he was waylaid by Peter Schott, who was one of the chief magistrates of Strasbourg, and was persuaded by him to come here instead?”

“I have heard the story,” Matthis Zell replied.

“And Peter Schott, who was also curator of the Cathedral, had the magnificent stone pulpit built for Dr. Geiler, with its nearly fifty saints, from which he preached for some thirty years to us here in Strasbourg. Perhaps you will also….”

Matthis Zell nodded and smiled as she halted her account.

“I had indeed heard.”

Katharina had stopped because she was suddenly embarrassed. Here she was again, dominating a conversation and comparing this man to Dr. Geiler. Perhaps he was intimidated by her words. Indeed, it was perhaps most unkind. Katharina herself did not like to be compared to others. It was sometimes humiliating and oppressing. She began another topic, trying to cover up her enthusiastic endorsement of Dr. Geiler.

“And your parents live there – in Kaysersberg? And have you brothers and sisters whom you will surely miss?”

She stopped again. She was such a waterfall of words and knew herself to be speaking overly much, something her mother was always warning her not to do.

“I,” she continued, suddenly shy and withdrawing her smile, “do apologize for talking too much and for asking such questions as are not really mine to ask. I surely over speak.”

“No, indeed,” he responded quickly, “too few people are interested. They think a priest is made only of black robes and has not a background of flesh and blood and is not interested in stories and such.”

This made Katharina grin in spite of herself, for she knew that there were indeed a great many priests who were very much made of flesh and blood, priests consisting mainly of bellies and greed.

“Why do you smile now?”

Matthis Zell’s curiosity was piqued.

“It is just,” and she spoke slowly now, not certain as to what she should reveal of her thoughts, “that I have known a great many priests who hid money pouches and slack flesh underneath their robes.”

He was quiet for a great many steps and she was afraid that she had been too bold once more and that she had offended him.

“I am sorry,” she began, “I did not….”

But he interrupted.

“No, you need not apologize. I am only too well aware of the iniquities of a great many men of the cloth.”

He sighed deeply at he made this statement.

“I am sure that you,” she began again, “especially from what I have heard of you….”

He cut off her words.

“Do not listen to what others say, Katharina. It is often only exaggeration and this often leads to disappointment.”

Katharina blushed. She knew herself rebuked and stared pointedly at her shoes before reverting the conversation back to the question she had asked him before.

“Do have you have family?”

This seemed a safe topic, and one that would not lead to controversy. Besides that, inside herself she was for some inexplicable reason so very glad that Matthew Zell came from the very same city in which her beloved Dr. Geiler had made his home and she wished to hear him speak of it.

“Well, I have a housekeeper, Mey-Babelli, who was cook to my aunt in Freiburg. When my aunt died, Babelli came to live with me and she takes care of me. So she is like family. But, yes, I also have one sister and one brother. My sister’s name is Odile.”

“Odile,” Katharina softly repeated, “that is a very nice name. I know no one by that name. Perhaps some day I will meet her.”

“Yes, perhaps you shall,” Matthis Zell nodded as he spoke. “As for me, I did not stay in Kaysersberg, and have not been back for a number of years except briefly to visit my brother who still resides there.”

“Where have you lived then?”

“Well, I served in the army for a short time. And this was the time during which I moved away from Kaysersberg and lived neither here nor there as the regiment I was with moved about quite a bit. And after serving in the army, I went on to enroll in the university of Freiburg in Breisgau. When I received my master of arts there, I continued with theological studies.”

“Why?”

Katharina knew it was another rather impertinent question and she looked back down at her shoes even as it flew out of her mouth.

But Matthis Zell did not appear to be put off by it.

“Because I did so love to study and the more I studied the more I loved it.”

“You felt not that you ought to study, in order to….? You only did it for the sake of the pleasure of studying? That is to say, you were not motivated by an inward call….?”

She stopped here abruptly. Her speech had consisted of unfinished phrases, and she knew quite well that her words sounded muddled, probably making very little sense to him.

“Motivated by an inward call from God?” he finished her last phrase, noting that her face was clouded.

“Yes,” she looked up at him now as she spoke, her blue eyes bright with interest, “for it seems to me that God has a purpose for all people and it also seems to me that if priests were to take such a purpose seriously we would not see all the vice that is so rampant in Strasbourg today.”

A voice within her, a voice that sounded remarkably like her mother, warned her that once more she had overstepped her oral bounds and had spoken too much and too quickly. After all, she had only just met this man. After all, her words accused the priesthood and the man walking next to her was a priest. She glanced at his face. In profile his nose seemed longer than it actually was. That nose was now pointing at the ground. It was almost as if the nose was sad.

“I’m sorry,” she murmured, truly repentant of perhaps having caused him discomfort.

He had been a source of easement to Frau Freiberg and Kristoff and the fact remained that she had only heard good things about him. He put her worries to rest by smiling, revealing even, white teeth.

Luther posting his 95 theses in 1517, by Ferdinand Pauwels

“No need to feel sorry. I’m glad you feel that you can speak your mind to me,” he replied.

“What think you of Luther and his views?” she said, blurting the words out rather quickly, for this indeed was a matter which nagged at her often, nagged her at night and in the daytime as well.

“Luther?”

“Yes, Herr Luther. You surely know of the priest in Wittenberg who has written at length about indulgences and who posted, just this last year, some points on the church door of that city.”

He smiled.

“Yes, I am acquainted with Herr Luther. I am, and have for some time, been reading a number of things that he has written. My parishioners obviously read him, and I ought to be aware of what they are reading.”

He smiled as he said this, but she did not smile in return.

“I would know what you think of his charter, of his theses,” she said, “for his words do touch my soul.”

“As they do mine,” brother Zell immediately rejoined, “as they do mine.”

“Do you think he speaks the truth?” Katharina asked.

“He is a very courageous man, in any case, to speak as he does. As you may know, he appeared before Cardinal Cajetan at Augsburg last October. They spoke for three solid days. Initially, I understand, Luther prostrated himself on the floor in a gesture of humility before the Cardinal, and the Cardinal raised him up as a gesture of goodwill. But Luther refused to take back anything that he said.”

“Yes,” Katharina very nearly stood still, turning her body towards him, her feet moving at a snail’s pace, “so I have heard.”

They had almost arrived at an intersection.

“He has said,” she cautiously went on, “that the person who truly repents has full forgiveness both of punishment and guilt, even without letters of indulgence.”

Matthis Zell looked at her rather quizzically.

“So I have read also,” he responded.

“And what thought you?”

“I think that the trafficking in indulgences is shameful,” Matthis replied, his eyes serious, “and it grieves me deeply.”

She heard that he meant his words and, although she knew the truth of them, was rather shocked by the sentences that followed.

“The public perception of the priesthood is appalling. Nearly all people disrespect the priests. There are so many examples of gluttony, of ambition, of lives of lasciviousness, of harlots being allowed into monasteries….”

He stopped rather abruptly. It was almost as if he had forgotten that she was there. She wished to reply; to say something intelligent, or, at any rate, something comforting, for she gauged that he was lonely. But there was nothing that came to mind.

And his voice, almost metallic now, continued.

“They say that the nearer people live to Rome, the less religious they are. How incredibly strange and despairing is that thought! And I have heard tell that there are those who care not what evil they do, for they say they can always get a plenary remission of all guilt and penalty by absolution and indulgence granted by the Pope for four or six or … or whatever sum of money they carry.”

The metallic tone in his voice had given way to a tremendous sadness – a sadness which distressed Katharina and which made her want to hold his hand to guide him away from such black thoughts. This she could do with little Jacob, but with a priest? No, of course not. But he did appear so mournful. She swallowed and was about to say something about the weather, when he went on again.

“Rome has become a harlot. The church has become blind to all but that which brings monetary gain. And we have so many poor, so many who stand in need of love and help.”

He stopped, seeming suddenly to remember that he was speaking with someone and was not alone.

“I am sorry,” he said. “I do indeed apologize for speaking so freely.”

She shook her head, cautiously replying, “I speak too much and too hastily myself. And what you say is true.”

She forgot that but a few moments ago she had sincerely worried about her hair coming undone, about a few stray strands flying about her face, for truly there were so many more important things to worry about.

“I have to turn off here at this corner,” she swallowed as she spoke, regretting that they were now close to the Johanngasse, “and you will have to keep on straight to reach the Bruderhof Strasse.”

“I know,” he said and she bit her lip yet once more for appearing to know the way better than he did.

“Well, Katharina,” and he spoke softly, as if to guide her into humility, “I have very much enjoyed speaking with you and hope we can do so again. I think I can tell you a story, perhaps the next time we meet, of an encounter I had with Dr. Geiler when I was but a small boy.”

Her eyes widened at this. He had stopped – stopped walking and stopped talking. She did too.

“You met Dr. Geiler when you were a little boy?”

“Yes, indeed. It was only a small encounter, but I should like to tell you about it as I gather you really loved him, this great preacher of Strasbourg. I also hope,” he then added warmly, “that you feel you might want to hear me preach some time.”

She vigorously pumped her head up and down, feeling several more hair strands escaping her hair net. In spite of herself, her hands flew up to smooth out and tuck in the rebellious curls.

“I would very much like to hear the story of your meeting with Dr. Geiler. And, yes, I would also like to hear you preach and I thank you for helping Frau Freiberg,” she ended the conversation rather lamely, sensing innately she had used a great deal too many ‘I’s’ in these sentences, yet adding, “and I bid you good-day, brother Zell.”

He smiled at her and the corners of his mouth, as well as the corners of his eyes, crinkled with the many laugh lines that the years had placed there. She was glad of it, for some of the weariness and sadness that had lined his face but a few short moments ago, disappeared. Looking into his friendly face, she flushed even deeper before she turned and walked towards the Johanngasse. After staring at her retreating figure for a few moments, Matthis Zell also turned and walked towards the Bruderhof Strasse.

Pick up your copy of Christine Farenhorst’s “Katharina, Katharina” at Sola-Scriptura.ca/store/shop.