Magazine, Past Issue

July/Aug 2025 issue

WHAT'S INSIDE: Screen-fast, sports betting, & environmental stewardship

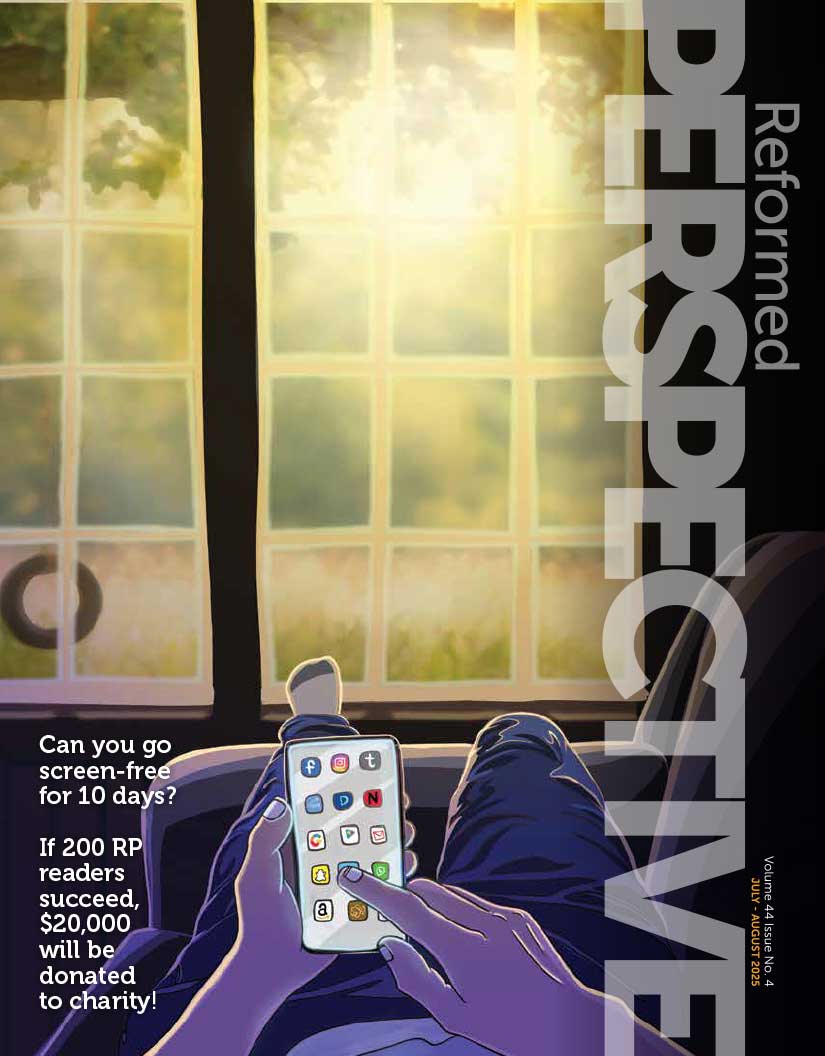

Our 10-day screen-fast challenge that we presented in the last issue is getting traction. Marty VanDriel has a story that shares how the fast went for him and others who gave it a try.

But that was just the start. Some generous supporters have recognized how important this issue is, so they are offering up a little extra motivation for us all. They have pledged to donate $100 to two fantastic kingdom causes – Word & Deed and Reformed Perspective – for every person who commits to and completes a 10-day fast from their screens from July 21 to 30 (to a maximum of $20,000 split between both causes).

Screens aren’t evil, but as the cover illustrates so well, screens can keep us from seeing reality – from seeing God’s loving hand upholding creation, this world, and our lives. Here now is your opportunity to join with some family and friends and maybe your whole church community to put screens aside and see the rest of the world unfiltered. Check out page 19 for more details or click on the QR code above to sign up.

Since sports betting was legalized in 2021, it has taken Canada by storm. If you watch any hockey you’ve noticed a lot of betting ads, and they bring with them a growing temptation for Christians to make some money while enjoying their favurite teams. But as Jeff Dykstra explains, we have good reason to steer clear of sports gambling.

In this issue we also do a deep dive into the topic of environmental stewardship by sitting down with two Christian women who work for an environmental group in the middle of a logging community in northern BC.

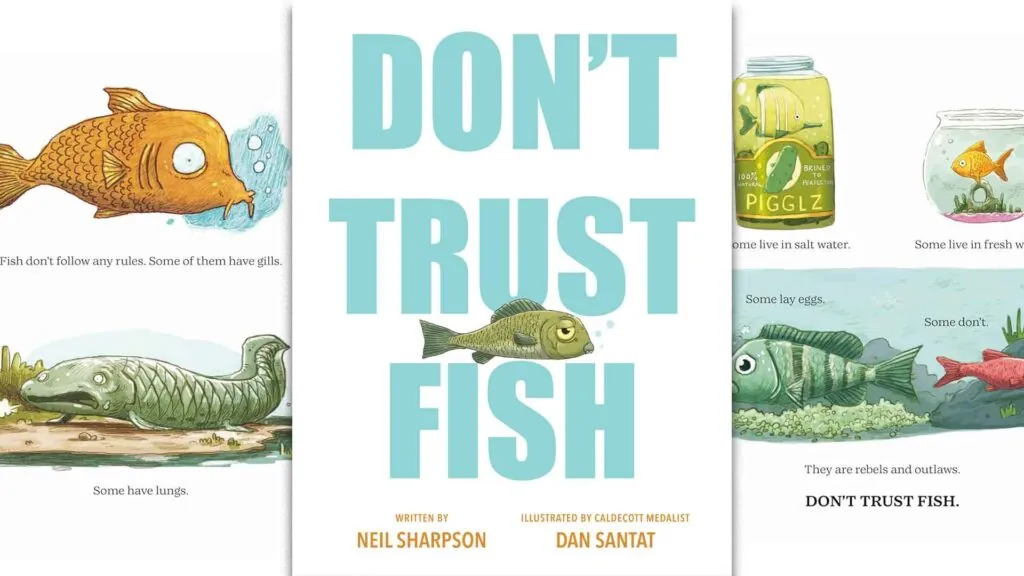

If you are an adult who tends to skip over the Come & Explore kids’ section, we encourage you to give this one a read. It will be sure to make you smile.

Click the cover to view in your browser

or click here to download the PDF (8 mb)

INDEX: Are you still able: A nation-wide challenge to experience life without screens / Creation stewards in a logging town / Who do you want to be? RP's 10-day screen-fast challenge / We took the no screens challenge... and now we're changing our habits / What can I do anyways? 35 screen-alternative ideas / Is TikTok the ultimate contraception? / How to stay sane in an overstimulated age / Defeated by distraction / How to use AI like a Christian boss / Who speeches were they? On AI, and others, writing for us / The Way / Who is Mark Carney? / What if we said what we mean? - the political party edition / Am I lazy or just relaxing? What does Proverbs say? / Get out of the game: Christians need to steer clear of sports gambling / Man up: ARPA leaderboards and the call to courageous action / Christians don't pray / Our forever home / Calvin as a comic / The best comics for kids / Fun is something you make: 11 times for family road trips / Come and Explore: Mr. Morose goes to the doctor / Rachel VanEgmond is exploring God's General Revelation / 642 Canadian babies were born alive and left to die / 90 pro-life MPs elected to parliament / Ontario shows why euthanasia "safeguards" can't work / RP's coming to a church near you

News

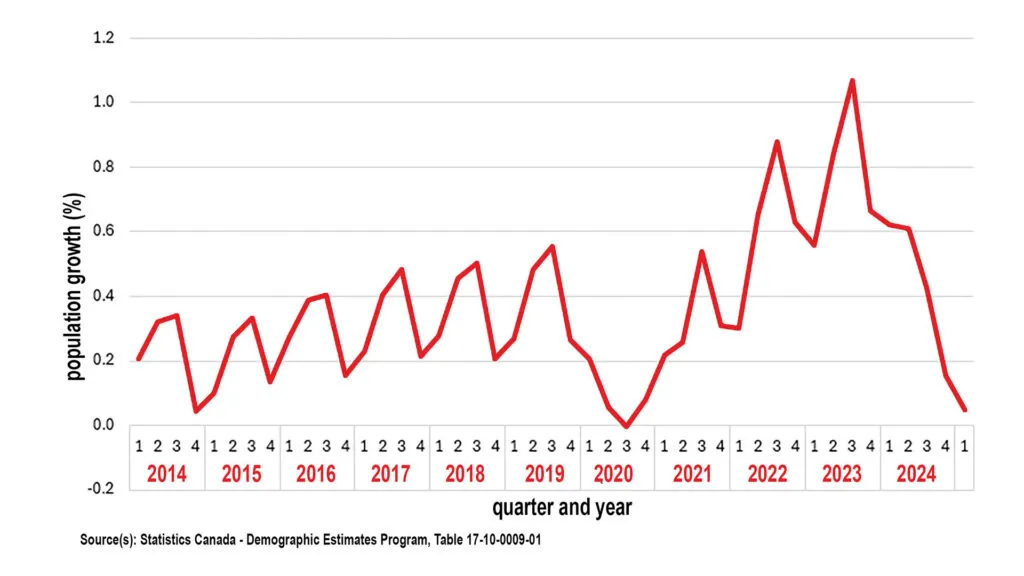

Canada’s population almost shrinking

The latest population estimation from Statistics Canada is revealing a startling change: Ontario, Quebec, and BC all saw population declines in the first quarter of 2025.

The country as a whole grew by only 20,107 people, which, as a percentage, amounted to a 0.0% increase, the second-slowest growth rate in Canada since records began in 1946. The record prior was the third quarter of 2020, when border restrictions from the Covid-19 pandemic prevented immigration. The decrease has been attributed to announcements by the federal government in 2024 to decrease temporary and permanent immigration levels, with targets of 436,000 for this year, which is still well above the 250,000 level prior to the Liberal government taking office in 2015.

So, in the first quarter of 2025 we lost 17,410 people via emigration to other countries, and there was also a drop of 61,111 in non-permanent residents – people on temporary work or student visas, along with their families. The data also shows that there were 5,628 more deaths than births in the first quarter, largely due to Canada’s quickly declining fertility rate. That’s a collective loss of population of 84,140 people.

Then, going in the other direction, we had 104,256 people immigrate to Canada, for that small net increase of 20,107.

While it is a blessing that people from other countries are still willing and able to move to Canada, it is sobering to note that two-thirds of the world’s populations are now below replacement rate and the world’s population is projected to start declining later this century.

God’s first command to humanity was to “be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it” (Genesis 1:28). Imagine what the world could look like in a few generations if Christians fulfilled this cultural mandate with enthusiasm while the rest of the world continued on its course.

Today's Devotional

July 9 - Fellowship and the world

“And the world is passing away, and the lust of it; but he who does the will of God abides forever

.” - 1 John 2:17

Scripture reading: 1 John 2:15-17; James 4:1-10

As the Scriptures speak to us about our love for God, one thing is very clear; our hearts cannot be divided in that love. Either love for God is the driving principle >

Today's Manna Podcast

The Resurection of Christ - It's Power: The Resurrection of Christ

Serving #898 of Manna, prepared by William Den Hollander, is called "The Resurection of Christ - It's Power" (The Resurrection of Christ).