“As water reflects the face, so one’s heart reflects the man.” Prov. 27:1

*****

Luke rightly says that out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks. That is to say, the heart is the core of one’s most basic beliefs, and words provide a glimpse into Man’s heart. It does not matter who a person is – butcher, baker or undertaker – words reveal his soul.

CHAPTER 1 – A baby at last

My birthplace of Harston in East Lincolnshire did not have a large number of inhabitants – neither before or after I was born. Hidden in rolling hill country, it was even considered backwater by some. But we always reckoned our burg, with its one to two thousand residents, as a decent size.

This number did not even take into account the souls who lived in outlying areas, tenant farmers and scattered cottagers, all of whom had a certain predilection for country living. Our town proper boasted a doctor, a lawyer, a banker, teachers, and a preacher. Housewives, clerks, carpenters, grooms and saddlers either paced or ambled the packed-down dirt sidewalks and children visited the local park to feed the ducks. There was even a railway station on Station Road and a small but well-stocked library straight across from it. Mercer Street had textile shops, an inn, and a bakery.

Harston’s roads, although not paved, were well-traveled. Days prior to the bi-weekly market held just outside its east limits, were alive with bellowing and bleating during the summer months – audible signs of life as farmers drove their four-legged produce through the streets to the local butcher shop for slaughter. The day of the market itself was noisy as well, roads abuzz with clamant vendors and townsfolk eager to bargain for good deals.

Although certain protocols were associated with living in our community, such as the few wealthier families having calling cards, the truth was that most of the citizenry were just common folk. A number resided in plain brick houses along the main avenues of Crown Street and Rudwall Lane. The balance of Harston’s inhabitants, however, lived in modest thatched homes on lanes akin to alleyways, and they lived without the benefit of butlers, maids, or cooks. Households were a decent size, with four or five children in each home. The homes, mind you, were small, often only consisting of two or three rooms.

We, my father, mother, and myself, lived on Hillbrook Street, a middle-class street, considered neither rich nor poor, and we had a small garden in the back of our two-story house.

My father, who was a self-appointed teacher of sorts, greatly admired the writings of the Anglican bishop, J.C. Ryle. Thus when I was born in 1889, I was named and baptized Ryle – Ryle Harrison to be exact. My mother later told me that I had cried lustily when the water dribbled down my forehead and that my father had been somewhat embarrassed by these wails. Nevertheless, she told me, her eyes growing soft as she spoke, he had cradled me in his arms with great tenderness and love during the ceremony. Hearing this as a young boy prone to admire Goliath figures, I was a trifle embarrassed, feeling quite keenly one should not use soppy words like “tenderness” and “love” with regard to men. But inside my heart I was warmed by the thought that my father, a rather stern but just man to be sure, felt more than a modicum of affection for me.

I was not a sturdy boy to look at. Rather skinny, fair-haired and prone to sniffles and coughs, there often rose within me a covetousness to be more strapping and robust.

But I run ahead of myself. When my mother was expecting me, there was rejoicing in our home on Hillbrook Street – indeed, there was a very great thankfulness. A baby coming at last after my mother and father had hoped and prayed for years and years.

We were, as I said, middle class and had the faithful, domestic help of a woman who had known Mother since she was a child. Plump, good-natured Cora, born and raised in Harston, was both our cook and maid, and she confidentially passed on to me many interesting paragraphs out of my parents’ diary – details of past events which had happened before I was born or when I had been but a little tacker.

“Master Ryle,” she would say, often expressing an opinion in double negatives, “Your mother was quite sure she would rock no cradle, never. And seeing as to how she’d been married to your father for more than fifteen years, I was quite sure she was right. But then many’s the time the stork’s visited them thought to be barren. And isn’t that the way of it?” Cora told me this while she was letting me lick out the bowl of pudding she had made for dessert that evening. With my mouth full of sweetness, it was difficult for me to respond. Not that Cora ever needed much of a response to what she was saying. She was as full of words as my mouth was of custard. My father often raised his eyebrows as she prattled on and I, ever trying to be like him even as I swallowed the pudding, raised mine.

“Yes, sir!” she went on, oblivious to my apparent surprise, “and your mother cried tears of happiness. It’s a good thing I was here to see to things – to cook and clean proper, mind you, because she wasn’t up to doing nothing.”

“Yes, Cora,” I mumbled, lowering my eyebrows again while I was licking the spoon clean, but she wasn’t listening.

“And that was the time, strangely enough, that the Sparrows moved into town. Not into Harston proper, mind you, but into the farmstead down Furrow Lane, to the south of here.”

I nodded again, scraping the bowl with the spoon for what was left.

“And wouldn’t Providence have it, but that Sarah Sparrow was expecting too. And wouldn’t Providence have it as well, but that she and Sam had also been praying and hoping for a little one for many, many years.”

Here Cora stopped yattering, quite out of breath. I sighed, sorry that the pudding bowl was shining and clean.

“And that’s how,” Cora ended her communication, “there was a friendship begun between Sarah Sparrow and your mother, Master Ryle.”

She lifted me off the counter where I had been sitting, patted my backside and shooed me out of the kitchen.

“Now off with you, young Sir,” she called, “for I have work to do and surely you want dinner tonight.”

*****

It was true about the friendship between my parents and the Sparrows beginning at this time. Sam and Sarah Sparrow had freshly moved in from London during the time when both my mother and Sarah Sparrow were expecting their first baby.

Sam, a burly, big fellow, was a farming tenant of one of the wealthiest farmers in Harston – Ryker Bitter. Ryker Bitter was the owner of one of the largest estates on the outskirts of Harston. He had lots of money, but possessed neither capacity nor willingness to share. As a tenant farmer, Sam Sparrow was better off than many farm laborers who occupied the very small and dank cottages of their employers. Although Sam did have to sign off a significant portion of his proceeds to Bitter, if he managed the rented property well, he could become fairly affluent. Sam and Sarah lived in a good-sized farmhouse and I loved visiting them.

Sarah Sparrow was adept at weaving, spinning and quilting, and had come by Hillbrook Street one day to show Mother a comforter she had made. Sarah had heard from other townsfolk that Mother might be interested in purchasing one. As the two women interacted in the front room, they naturally began to speak of the coming births of their babies. A common bond was kindled because both had been forced to wait for more than a decade for their first child. Mother was due a month before Sarah Sparrow was expected to give birth. They promised one another that they would visit back and forth. They laughed with one another as visible kicks poked bumps into their aprons, and they discussed myriad names for their unborn progeny.

CHAPTER 2 – The birth of Samwell

When Mother began labor it was a week or two before her time, so Cora told me, and it was a misty and rainy night. Unhappily, the Harston midwife was visiting a daughter in London and the doctor was late in coming. To all appearances it seemed that I would be born without medical assistance. My father, Cora said, was in such a nervous state that he was ready to go and carry the man to Hillbrook Street on his back, but he did not want to leave my mother alone. “I thought a teacher and an educated man like your father,” she spouted philosophically, “wouldn’t have been so fretful.”

I stared at her.

Cora then added matter-of-factly, “He didn’t place no confidence in me delivering you neither.” I nodded sympathetically, rather liking the fact that my birth had been the focus of such attention, and sat up straighter. Cora was polishing the silverware, allowing me to hand her the forks and spoons as she worked.

“Did the doctor finally come?” I asked, even though I knew the answer.

“Yes, he did,” she sighed, even as she rubbed a cloth over a butter dish, “but he was a sorry case, he was. Wet with rain, he dripped all over the hall carpet, he did.”

“And then what happened?” I prodded her, even though I knew perfectly well what she would say next.

“Well, your father yanked off the doctor’s coat so fearfully hard that the man almost fell over, and then he proceeded to pull him up the stairs.”

“And he forgot his bag,” I added, for Cora had forgotten that part.

“Yes, indeed! And once he was up, didn’t he have to go down and fetch it a minute later?”

I smiled. Dr. Pillblight was a sour man, to say the least, one who rarely gave patients a smile. It was a game with me to try and make him do so, but his lips seemed permanently frozen to scowl. Yet he had been forced to walk down our stairs to get his black bag when I was about to be born. That was something which made me smile.

“And then coming down the stairs, he tripped,” I went on, “tripped and sprained his ankle.”

“Yes,” Cora affirmed, her round cheeks quivering busily as she nodded her head, “and this was just when there was a knock at the door and when I went to answer, there was Sarah Sparrow standing on the doorstep.”

“And she livered me,” I proudly went on.

“Delivered, Master Ryle,” Cora corrected, shaking her buxom jowls this time, “the word is ‘delivered.’ And she herself as big as a volcano about to erupt.”

So it came about that Sarah Sparrow helped Mother during the last part of her labor and she it was whose hands first lifted me up and laid me on my mother’s belly so that she could see me. A skinny youngling, puling and oblivious to the people about me, Mother says I kept my eyes shut for two days.

*****

Mother never let Sarah’s act of kindness nor her expertise at midwifery slip from her memory. Father remembered it as well, and in this way a true friendship was forged between our two families – the families of Harrison and Sparrow – and, consequently, between myself and Sarah’s baby.

*****

It was during the month after I was born that Sarah’s time of confinement also came. When Mother heard, via Cora and other townsfolk, that Sarah was in labor, she walked down to the farmstead where the Sparrows lived. Mother pushed me, a six-week-old baby, along in a pram. With big wheels and a wooden handlebar, it bounced me up and down, up and down, but it did not deter Mother’s determination to go to her friend.

A container of broth for Cora was positioned precariously on the blanket by my feet, and mother carefully avoided large potholes and mud puddles. Arriving at the Sparrows’ home, she gingerly lifted the soup out of the carriage and carried the pan to the back door. Met by Ruby, the midwife, she asked if there was anything she might do to help. Ruby took the soup from her hands, smiled and was about to send her home when a voice from the bedroom cried out.

“Is that Maudie? Please, I want to see her.”

The midwife shrugged and stood back. Mother, however, did not walk in straightaway. She first returned to the carriage, and lifted me out. Then, with me in her arms, we both entered the farmhouse. I was sleeping soundly, drooling milk bubbles on my chin, so Mother later informed me, and thus do not recall a word of the conversation that ensued between mother and Sarah. Cora, who was close with Ruby, later told me that Sarah had been greatly distressed, distressed to the point of tears.

“Something’s wrong, Maudie,” she had burst out while the midwife was bringing the soup to the kitchen, “I know something’s wrong.”

“Hush,” Mother replied, dandling me, “Hush, dear. I know things are difficult right now, but just wait. Before you know it, you’ll be holding a little one just as I am holding Ryle.”

“No, I am afraid. Please pray with me, Maudie. Please!!”

So Mother prayed. With me in her arms, she prayed for a well baby, a healthy life, and a healthy mother.

“Pray it again, Maudie. Pray that the baby will be well.”

So Mother prayed the same words again. Years later, years after little Sam was born, my mother still vividly remembered that she had been sure that Sarah’s instincts about her child had been right.

At that moment she would, without fail, add these words: “But there is no sin in asking God for wellness, is there?”

Ruby, who had been listening in the doorway as Mother prayed, was all ears, and it was mainly her blurting out that prayer to Cora and others in town that caused Sam’s name tag to become Samwell.

*****

Sheep farming and the wool trade brought profitable business to our area. I mention this only because Sam Sparrow raised sheep and he was good at it. Ryker Bitter rented out farmland to Sam Sparrow. He used that land, called in-bye land, for pasturing heads of sheep. As well, Sam hunted grouse and other wildlife on that land, and often sold produce at the market. The wool from his sheep, Lincoln Longwool, was much in demand and he did rather well in bartering with certain textile manufacturers. His sheep produced the heaviest, longest and most lustrous fleece and it made hard wearing cloth.

Although a great deal of his earnings disappeared into Ryker Bitter’s pocket, Sam himself also gained financial standing. The eastern port of Boston, not too far off, was a place of economic interaction. Centuries before, the merchants of the Hanseatic League had established their guild in Boston and many ships came to its port. There had been issues with water diversion to neighboring fens, but a canal had been cut, and a sluice constructed. The result of these endeavors was a navigable communication, of a lucrative nature, with a number of shires, our shire included. Boston was a major trading center for wool and Sam Sparrow had been born to raise sheep. My father sometimes joked that instead of herding children, he ought to herd sheep. But then mother would remind him that the children in his study were also sheep and he would laugh and pat her on the cheek.

Samuel Sparrow was born later that same day – that day my mother had visited Sarah, pushing me in the pram. Baby Sam was born with a short neck, a flattened facial profile and his almond eyes seemed slanted. Ruby, the midwife, was a bit disconcerted by the way the neonate felt somewhat floppy in her arms; by the fact that he made no effort to squeeze her hands. Consequently, on the third day after his birth she sent for Dr. Pillblight who arrived carrying his black bag. After he had examined the baby thoroughly, testing reflexes, and peering at his toes and fingers, he took off his glasses.

“Well,” he finally slowly asserted, as Ruby laid the baby back down in his cradle, “Well, I may as well tell you straight off that the boy is going to be slow.”

Sam was sitting on the edge of the bed and holding Sarah’s hand. Ruby retreated to the doorway. “Slow?” Sarah repeated, a worried look on her face, as she pushed her head back into the pillow, “What do you mean ‘slow’?” Sam said nothing, but let go of Sarah’s hand. Then he stood up and deliberately walked over to the cradle. There he remained, studying his placid child.

“I mean,” the doctor continued, and later Sarah told Mother that he had actually been quite kind and sympathetic, “I mean that this boy ….” He stopped and searched for words before he continued. “This boy has all the characteristics of babies in a study I have been reading by a Dr. Down, a Dr. John Langdon Down to be precise. He fully describes some things in this study which I see in young Samuel here.”

“What do you mean?” Sarah reiterated, “What do you mean ‘slow’?”

Dr. Pillblight settled himself in a chair opposite the bed. “I mean,” he continued, “that Samuel will probably be slower in learning how to walk. He has poor muscle tone. He will also very likely be slower in his mental ability.”

Sam and Sarah stared at one another and Sarah’s eyes filled with tears.

“Although,” Dr. Pillblight continued cautiously, “it has been recorded that some children with these characteristics ….”

He could not finish because Sam interrupted him. “What characteristics?”

“Well,” Dr. Pillblight rose and walked over to the cradle and stood next to Sam as he discoursed, “characteristics such as the wide space between his big toes and the other toes. Also, note that he has a very short neck and that his hands are very short.” As he spoke, he uncovered the child to demonstrate what he had just said, and Sam again stared down at his unperturbed and sleeping son.

“Note also,” the doctor went on, “the baby’s slanted eyes.”

“I had noticed that his eyes were unusual,” Sarah later recounted to my mother, “and suddenly, looking at the baby’s face as the doctor spoke, I knew that what the man said was true. Also, Samuel’s tongue often came out of his mouth, almost as if it was too big for him to hold in.”

Sam Sparrow broke the ensuing silence, albeit fumbling for words. “What …. What can we do?”

The doctor shrugged. “Just take care of him,” he answered, “the study shows that children with this … this abnormality, are susceptible to ailments. Some die in infancy; others live longer. It’s in the hands of God and you will just have to take good care of him.”

He stooped over, picked up his black bag, and then, after a greeting, was gone.

*****

Once she had finished grieving over and contemplating the fact that Samuel was a delicate and different sort of baby, Sarah proved to be an excellent mother. For one thing, she was very innovative. She devised ways to help the baby sit up. Talking to him continually, she coaxed sweet smiles from the flat, little face, crinkling the almond-shaped eyes.

Wrapped up warmly, Samuel was taken for countless strolls. There was no place in Harston which did not recognize Sarah and her son. Most importantly, when people stopped her to have a look inside the carriage, she would not be ashamed. She bragged on him as if he were the most important, delightful and charming baby in the world. And because this baby was so beloved, he never stinted in giving spectators beaming smiles.

Sarah often took Samuel, or Samwell, as he was beginning to be called by everyone, to Hillbrook Street where we lived.

CHAPTER 3 – A beginning of books

As I said before, my father was a teacher of sorts. (Although I hasten to add that he actually had no need of employment because he was a gentleman. That is to say, he had a good personal income from his mother’s side of the family.) But he loved reading, studying various kinds of books, and took much pleasure in passing on his knowledge. I cannot recall a single evening when he did not peruse a book or a magazine of some sort with me. It was not until much later that I realized the enormous benefits I had reaped from having such a father.

The 1800s had been a time period of much academic poverty in England and Wales. Out of the four plus million children of primary school age, two million received no schooling at all. Religious institutions had been set up by the church to teach children reading, writing, arithmetic and religion, but they did not meet the needs of the growing population. In 1870, about twenty years before I was born, the Elementary Education Act had been passed in Parliament to address the issue of poor children who were not being taught. The Act specified that school places were to be given to all children between the ages of five and twelve in schools run by qualified teachers. A fee was required though – a varying fee of between one and four pence a week. If a family could not afford such a fee, children could attend classes for free. But not many did.

Before father had begun to transform our very large back room into a classroom, there had been a school of sorts on the outskirts of town. It had been run by a Mr. Dauper, a man who, as my mother said, was as addicted to a bottle of wine as he was to caning children. Supposed to be overseen by board members, this establishment was not well-run. Father visited the school once in the second year he and Mother moved to Harston and he came home much incensed. After speaking with several local officials, Father eventually became the new teacher and our back room was transformed into a classroom. It was an unusual situation, but my father was an unusual man. (There was a school in a neighboring shire, and a number of local children did attend that school.)

When I was little, Mother and I often visited the Sparrow farmstead and they, in turn, visited us. Consequently, Samwell and I became compadres, brothers almost. In the beginning, both in nappies, we just slept side by side in front of the hearth. Later we played together, with me usually being the leader and Samwell agreeing, smiling, and a willing partner to most of the things I invented for us to do.

When Father read to me, as he did most days, and Samwell was present, both of us would sit on his lap. I usually fidgeted at Father’s stiff, starched collar which he would eventually take off and drop on the floor. At first he read us A,B,C books, Mother Goose, Jack and the Bean Stalk and the like; later we graduated to Robinson Crusoe, Rip Van Winkle, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Children’s Stories from Dickens.

When we were at the Sparrows’ farmstead, however, it was Sam Sparrow who read to us and not Father. Sam, although he did not shun A,B,C books and such, tended to stick to Bible stories. I did like the timber of his well-modulated, heavy voice and I will never forget how he related the way in which God created Adam from the dust of the ground. Sam stood up for this story, and picked up some imaginary dirt from the ground. After this he straightened his position, held the dirt in his arms like a baby while he rocked back and forth, gazing on the imagined dirt tenderly. Then Sam Sparrow bent his head and breathed the breath of life into this earthen baby.

Samwell listened intently. He always did. I can still see him leaning his large head back against the cushion of the rattan chair, almond eyes steadily fixed on his father.

So we grew – grew out of our nappies and were breeched, although I was breeched a full year before Samwell. He did not get his first pair of pants until he was four.

We grew on, Samwell and I, into bigger and bigger lads. It is true that many things, things such as the breeching, took longer for Samwell. Indeed, it sometimes took him years longer to attain a level that I had achieved in a few months. It did not impact our fondness for one another. Samwell was never scanty with his smiles and affection. Though he did not speak quickly as a young lad, he babbled on so incessantly and gestured so amiably to all who would pay attention that he was a favorite of many folks in town. Sarah, as well, often read to him during the day, and with the help of my father, she obtained picture books. When Samwell saw things illustrated, he learned much quicker.

Sam Sparrow, when he was able, always came in for the noon hour meal, frequently bringing men with him who were helping him with the sheep, because such was his success with the sheep raising that he was able to hire others. On one such day, when Mother and I were visiting the Sparrows, and Samwell and I were about four years of age, Sam and two of his men were seated at the table. Sarah and my mother were serving them fresh bread and some soup. Before eating, Sam Sparrow took off his hat and motioned that his men should do the same.

“Let’s say grace, lads,” he announced, his voice pleasant and sure.

Then he began.

“Our Father in heaven, we thank You for this fine food. Bless it we pray and we thank You for ….”

He did not finish. The side door opened as he spoke and it opened with an intrusive creak. The noise trespassed into Sam’s prayer and was followed by its architect, Ryker Bitter. The man strode in boisterously, blatantly ignoring those sitting quietly around the table. We boys, Samwell and I, standing next to the table, watched him enter with our eyes wide open. Ryker was a large man and he had to bend his head so as not to bump it on the low door lintel.

“Well, praying are we,” he began, “and what are we praying about?”

Sam Sparrow scraped back his chair – a wooden upright one with a woven seat – and stood up. “We are thanking God for our meal,” he answered simply and clearly.

“And what are you eating today, Sam?” Ryker mocked, “Is it a meal worthy of thanks? Well, will you look at that! Some plain bread and some watery soup.” He laughed and cracked his knuckles at the same time.

“When God provides food,” Sam Sparrow countered, “then it is a fine meal. And we ought to thank Him for it.”

“Has He blessed you with a fine son too, Sam? Has He given you a fine child as well? I hear tell he’s a bit slow. It would be a long time before I would thank God for a child like that!”

The truth was that Ryker and Alice, his wife, had no children. Mother and Sarah stood silently at the board as Ryker was speaking. Both were motionless. I was closest to the door and could feel the vibration of Ryker’s boot as it tapped the wooden floor. His boots were made of black leather. “Now that’s a frail-looking tyke as well,” Ryker boomed on, inspecting my person, “But well, I’ve not come to discuss food or children. I’ve come for the payment due on the farmstead, Sam.”

Mother walked over and reached for my hand. Then she walked me back to the board and resumed her position next to Sarah. Samwell had said not a word, but stood dreadfully still, his hand grasping the back of his father’s chair.

After Sam Sparrow and Ryker Bitter had left the room, it was as if an audible sigh of relief swept through the room. Mother walked over to the table and ladled soup into the bowls of the men. Talk resumed. Samwell laughed and was lifted into his special chair by Sarah, and I climbed into mine right next to him.

The truth was that Ryker Bitter was easily the wealthiest man in the area. There were very few who dared to contradict him; very few who would consider disagreeing with him over even such a small matter as the weather. If Ryker Bitter complained that the sun was too hot, many would nod even though it might be a mild day; and if the man suggested that it would rain, umbrellas were taken out even though the sky overhead was blue.

CHAPTER 4 – Growing in wisdom

My father, and here I repeat myself again, was a self-appointed teacher. He loved reading and writing and did much of both. He had transformed our back room into a classroom and it was a classroom free of charge. For many of the fathers and mothers in Harston’s poorer section, however, sending a child to school, even a school free of charge, meant the loss of a much-needed income, for often a child would be working at a job. Attendance at the school which had been run by Mr. Dauper had been poor at best, especially at times of harvest.

Father made it known, I don’t know how, perhaps by word of mouth, that he was willing to teach at any time to anyone disposed to learn. And so a steady stream of local boys passed through our home at odd times. Sometimes they would come an hour or so in the early morning, and sometimes evenings were convenient. They would knock and Cora let them in. She would instruct them to take off their shoes in the hallway and to hang their coats on one of the many wooden nogs that father had attached to the wall in the corridor. After thus being properly introduced to the house, they were ushered into Father’s study.

When I grew older, I was usually seated at a small wooden desk, hard at work when they came in (provided they came in the morning). For me there was reading, writing and arithmetic. Later Father added grammar, geography and history, being most insistent on that last subject. And gradually I advanced to other subjects – Latin, French, algebra and geometry. The local boys, however, were taught mostly to read and write, add and subtract. They were a serious lot, these boys who came.

From time to time, Samwell also came to school. When Sarah visited with Mother, Samwell would inevitably find his way into the study. Father never forbade him. Samwell was rarely distracting to those who were learning and the other boys tolerated him with rather good humor.

At first Samwell would simply sit on the floor of the study and watch me and the others. Whether we were reading, writing, or attempting to work out a mathematical problem, he was fascinated. After a while he would stand up and peer over someone’s shoulder. If I, or anyone else looked at him, he would tilt his head and flash such a huge smile that no one had the heart to send him back to the floor. Standing behind me, he would often count the fingers of his right hand. It had taken Sarah a very long time to teach him this, and he himself was very pleased with this accomplishment. Laboriously and slowly, he was able to say the numbers one to five with as much conviction as if they were the breath of life to him. The action pleased him to no end and he would do it over and over, proudly and loudly. Father would eventually shush him and he would sit down on the floor again, his voice dropping down to an almost inaudible whisper, his hand held up in front of him as if it were a slate on which to draw.

There was another subject which drew Samwell like no other. That subject was religion, or Bible stories. Doubtless because Sam Sparrow read to him most evenings out of the Bible, the boy was replete with the commandments, the prophets and all the stories of the New Testament.

Actually, to say that Sam read to his son is a bit of an untruth. The truth is that Sam chanted or sang the stories to his son. Samwell could retell, or re-sing them in his own fashion, the favorite-by-far story being that of the good Shepherd. Samwell’s rather large, and sometimes protruding tongue, sometimes made his speech less than clear. At times it caused some of the village children to make fun of him, especially if he was singing one of his favorite songs while walking down the street. But woe to these children if one of the boys who frequented Father’s study was close by. Quick punishment awaited them and Samwell, hardly aware of the mocking to which he had been subject, generally smiled his way through town. Singing in his low-pitched voice, although he could barely carry a tune, did not deter him from interacting with other folks, many other folks.

Samwell was good friends with Mrs. Dalfry, who lived just outside Harston on the east side. She kept a rabbit warren in an enclosed field by her cottage. She farmed the rabbits for food and fur. The dry and rather sandy meadow tract by her home was enclosed with water-filled ditches to stop the coneys from escaping and she had fences to keep out the predators. Her husband, long dead, had been a warrener, someone who kept rabbits. He had built several oblong “pillow” mounds with stone-lined tunnels for the rabbits to live in. His was a rare occupation but rabbit meat was a delicacy and the price of rabbit meat and fur made it a rather lucrative business. Being that she was close to the market, Mrs. Dalfry often ran a rabbit booth.

Samwell loved visiting Mrs. Dalfry and her warrens and she was fond of the child, often inviting him in for a chat of sorts. They would stroll in the field and she would show him the rabbits. Affectionate and happy, it was obvious that he loved her as well as the rabbits.

Mrs. Dalfry was not Samwell’s only friend. I believe he visited more people in Harston on a regular basis than our pastor, John Solls, who lived but a few houses down the street from us. Samwell also frequented Mistress Toynder, the baker’s wife, who often gave him a cookie as he passed by; as well there was Joe Cobb the chimney sweep, who betimes let Samwell follow him and watch him work as he climbed some of the wealthier chimneys in town; and there were the countless grooms, housekeepers, clerks, carpenters and maids, all of whom developed a fondness for the child, or, as the years went by, for the kind and simple-hearted man Samwell was on the way to becoming.

There was one person, however, who truly harbored no love for Samwell. That person was Ryker Bitter. Ryker actually had no great liking for me either and it could probably be surmised that he had no great liking for anyone besides himself. Still, for the young lad Samwell had grown into, the wealthy landowner showed an especial aversion. I believe that Samwell himself was aware of the animosity exerted towards himself by Ryker. When street-children mocked him, or laughed at something he did, he laughed right along with them. On the other hand, when Ryker Bitter stopped him on a path, or singled him out in the farmyard by his house and made degrading remarks, Samwell was puzzled. His almond eyes furrowed and he did not smile. He did not understand. He could not fathom that someone might not like him as he himself liked others. It pained him somewhat to see Ryker Bitter deride him. Not for his own sake, but for the man’s sake. There was this singular characteristic about Samwell in that he was uniquely loving. That is to say, he understood much more with his heart and mind that most people gave him credit for. He could not always express with his mouth what his heart thought, but he felt, oh, he felt much and he sensed that Ryker Bitter was unhappy.

*****

School-leaving age was generally around the age of fourteen. When I was a year and a few months past that age, my father tested me and judged me ready and qualified to write an entrance examination into a higher school of learning. There were two examinations for the University of Cambridge: the Junior (for students under sixteen years of age, into which category I fit), and the Senior (for students under the age of eighteen). These examinations took place in local “centers” – places like schools or church halls. The subjects the students were tested on were many and sundry. They included such topics as English language and literature, history, geography, geology, Greek, Latin, French, and so on.

School exams took place over a period of six consecutive days and were set in the morning, afternoon, and evening. My presiding examiner arrived by train at the Station Street station. He wore a black, high hat and appeared very impressive. Upon seeing him, Samwell immediately asked his mother for a similar headpiece. She laughed and told him to ask Joe Cobb, the chimney sweep who wore a stovepipe hat. My heart was in my throat as I walked towards the church hall the first day. Both my father and Samwell accompanied me to the door.

Father shook my hand. “I know you’ll do well, Son.”

Samwell beamed a grand smile of affection and followed Father’s example of handshaking. “Do well, Ryle.”

*****

Much to my relief, I did do well. The questions were easier than I had anticipated. For example, one of the questions in History was: Name in order the Queens and the children of Henry VIII. On what grounds was he divorced from his first wife? In Religion one of the questions read: In what three ways was our Lord tempted in the wilderness?

*****

These, and other questions posed, did not present much difficulty and I passed the examinations with flying colors in those particular subjects, as well as in some others, much to Father’s gratification. The only discipline in which I needed help was French, and Father was to tutor me in that during the next few months. Samwell was pleased also. He had not understood much of why I had to be at the church hall and stay there for a length of time each day during the week that I was examined. But he did know that it was important for me and was always waiting when I came out the side door.

“Do well, Ryle?” he would ask me with his guttural tongue.

I would nod and he would clap his hands in glee and follow up by thickly shouting, “Good, Ryle! Very good.”

CHAPTER 5 – A good shepherd

We hadn’t seen much of one another that summer, Samwell and I, as I had been busy studying with Father preparing me for the examinations. But Samwell had been training with his Father as well, who was grooming him to become more self-sufficient. It seemed only logical that Sam Sparrow, the sheep owner, should prep his son to take care of his own little flock of sheep.

Sheep can be kept in a barn or some other enclosure fairly easily. There was a small barn near the Sparrow farm. It stood on one and a half acres of land in which Samwell was now keeping ten sheep. He was inordinately proud of his little flock and spent much of his time counting the sheep on the fingers of his hand. He knew that if he counted his hand twice, then that was the number of sheep he had. Samwell was also meticulous in storing bedding and feed inside his barn.

“Sheep don’t get very cold, Ryle,” he confided in me. “They are warm animals.”

I nodded.

“Food for sheep has to be dry, Ryle.”

I nodded again. Truthfully, I did not know these things and was happy Samwell was learning a trade of sorts. “Sheep need room to move, Ryle. In the barn and outside.”

“You know a lot about sheep, Samwell.”

He grinned broadly, all teeth showing. Then he proudly went on to tell me that his sheep had to be careful. “Foxes kill lambs, Ryle.”

“Foxes?”

“Yes, Ryle, red foxes. And,” he added suddenly remembering, “badgers too, Ryle. They hunt lambs too.”

“You do know a lot about sheep, Samwell,” I repeated, clapping him on the back, “and they are so happy, I think, to have you to look after them.”

“Mother likes wool, Ryle. When sheep stay outside, they have clean wool.”

“Will your sheep stay on this piece of land, Samwell? Won’t they wander off?”

“No, Ryle. I fixed fence with Father. See, I will show you.” He did show me, and the stone wall that enclosed the section of land Sam Sparrow had given his son was in good shape, measuring some three feet high.

“That’s a sturdy wall, Samwell.”

“Father fixed most of it,” he modestly replied, but then grinned, adding, “but I carried stones too.”

I believed it for Samwell’s hands, though short, were strong.

“Where do your sheep drink, Samwell?”

“Trough in the barn, Ryle. I change water every day.”

“Samwell, I think you will become a teacher in sheep-raising and you can give lessons to all the children in Harston.”

Samwell chortled so hard that he almost fell over.

*****

Father and Mother and I had a long talk about whether or not I was ready to leave Harston and go to Cambridge.

“I waited for you so long,” Mother complained, without looking at Father, “and now before you are sixteen you plan to leave us.”

“The boy will be home for holidays,” Father interspaced, as Mother was gearing up to say a lot more.

“Well, it wouldn’t hurt him to study with you for another year, or at least a half a year,” she pleaded. “He will probably learn much more from you than he would from all those strangers who don’t really know him.”

“Maudie,” Father tried again, “the boy needs to leave sooner or later. And the sooner he leaves, the sooner he’ll be home again.”

“That’s not true,” she countered, adding with a sober face, “Sometimes I wish that Ryle was like Samwell. Then he’d stay home.”

Father and I looked at one another in astonishment. “Maudie,” Father whispered, “you don’t really mean that. God has given each boy talents – Samwell as well as Ryle – and each must use his natural ability as best he can.”

And in my mind, I could see Samwell standing by the sheep pen, hugging the lambs and leading the animals to a salt lick. And I could hear him speak with his hands, with his five fingers. Often his sentences had just five words. “My name is Samwell Sparrow” and “He said: ‘Feed my lambs’” and, most telling of all, “Bring good news of happiness.” They all fit on his fingers, those words.

“What good news of happiness, Samwell?” I asked.

“Jesus, Ryle. Don’t you know? The good news of Jesus.” He raised the fingers of his right hand as he repeated the last five words. And then he smiled.

*****

The upshot of the matter was that I did stay home for another six months. It was a compromise of sorts between Father and Mother. Father did continue to teach me half-days with a strong emphasis on the French I had fallen short in. I was, truth be told, happy as a lark to put off leaving. Change was not my venue. I was not adventurous and often I spent part of these my reprieve-from-Cambridge-days roaming the woodlands with Samwell. He was a good walker and we saw bitterns, red kites, kingfishers, foxes, and hedgehogs. Samwell loved animals. One such day in the late fall, he stopped.

” I show you something, Ryle?”

We were walking down a path and had just stopped to eat a sandwich. “Sure, Samwell.”

Samwell held up his left hand and counted the fingers with his right. “The Lord is my Shepherd.” Again, the words numbered five and fit on his hands like a glove.

“That’s good, Samwell,” I praised. “Did your mother show you that?”

He shook his head. “No, Ryle. I showed myself.”

“Well, that’s very clever and true.”

“Can you do it too, Ryle?”

“Yes, I suppose I can.” I lifted my left hand and counted fingers with my right saying as I did so, “The Lord is my Shepherd.”

“Good, Ryle,” Samwell approved. Then, aping my Father’s often used words for himself, he added, “You are a good student.”

*****

A few weeks later we were out again. It was a day with a steady drizzle, every now and then upgrading into a firm rain. Walking proved mucky and difficult on the country paths. Stone walls guarding the side of the lanes were wet and shiny. Following along in ruts made by wagon tracks, Samwell stomped through puddles and cheerfully sang songs. He loved mizzling weather and, as he was frequently subject to colds, Sarah always made sure he wore a thick coat when he went out.

Around one particularly steep bend, we suddenly stopped. Among the small copse of apple trees we were just skirting, there was a pitiful, bleating sound. Distressful and whiny, it crept past the Kirton Pippins with their yellowish-green skins and dull red flush, slid over the wagon ruts and halted by our boots. Samwell immediately began scouting the sides of the road.

“That is a lamb, Ryle,” he told me, and I nodded.

We found the creature fairly quickly. Almost in the ditch, it was lying in a clump of wet grass. The apples suspended above the pathetic, whining sound, looked ready to be picked. Perhaps some farmer driving a flock to market and hungry for the sweet bite these apples offered, had stopped for a snack and perhaps because he was inattentive at this point, one of the lambs of his herd had been able to wander away from his protective custody.

But I was wrong in my conjecture, for it was the very smallest of lambs which Samwell scooped up in his arms, a lamb still covered in wet amniotic fluid, a lamb that had its umbilical cord still attached.

“Oh, Ryle,” he called out, even as his round face coughed into the dankness of the place, “Oh, Ryle, this is a newborn baby. But no mother!”

Samwell was almost weeping with concern. Unbuttoning his great coat, he cradled the lamb within its folds and informed me that this pretty, little ball of fleece ought not to get cold, because then it would die.

*****

We set off at breakneck pace back towards Harston with Samwell breathing noisily and having a difficult time catching his breath. As we half-walked, half-ran, taking this path and that as we headed home, the thin shower of rain became almost negligible. A blue sky and a bright sun materialized. The lamb had stopped its mournful cries and appeared to be dozing peacefully against Samwell’s chest.

“We have to find mother, Ryle,” Samwell kept repeating as he wheezed. “We have to find her.”

Fifteen minutes into our rush back, we had wandered onto the deer park adjacent to Bitter Hall, the home of Ryker and Alice Bitter. When Samwell turned towards it, I was a little hesitant and, voicing my objections, told him of my hesitancy about walking onto their property.

Samwell, still sheltering the lamb, paid no heed. We were on the Servant’s Trail, the trail used by those employed on the estate, those who helped keep the place running. Although a section of the trail was a short-cut back to Harston, Samwell seemed intent on heading towards the estate itself.

“Ryker Bitter has ewes, Ryle. Ryker Bitter will have mother. Mother will have milk,” he panted as we headed towards the large, thatched manor house.

“But Samwell,” I pleaded with him, “Ryker Bitter may not let you into his barn. He might not like it that you are here on his property.”

We could now see the stone and timber barn that belonged to the Bitter estate and that is exactly the place towards which Samwell’s feet moved.

“I’ve visited with Father. This way, Ryle!” he called out over his shoulder. “This way!”

It was at this point that we met Jacob Crew and Daniel Shutter, two of my Father’s old pupils, and big fellows they were. Both were efficient gardeners and thatchers. Indeed, there were many in Harston who hired the pair to repair their roofs.

“Hey, there, Samwell and Ryle,” they called out in a jovial manner, carrying shovels and rakes and pushing barrows, “what brings you down here?”

Samwell stopped, coughed, smiled for a brief moment, and I explained to Jacob and Daniel what his mission was. Jacob was a little dubious and eyed the lamb reclining beneath Samwell’s coat with a certain amount of disbelief. Daniel just shook his head.

“I don’t know,” Jacob slowly worded, rubbing his chin, “I can take you into the barn and I’m quite sure there are a number of ewes who have recently lambed. Perhaps ….” He left off speaking, waved his hand, turned around and guided us towards the barn.

“Ryker’s not the easiest fellow for whom to work,” Daniel confided as he too turned and walked along with us, “but I don’t see why you can’t check the ewes. Where’s the harm in that? Nowhere, to be sure.”

With its thatched, hip roof and its white-washed stone walls, the barn was rather massive and overwhelming. As soon as we walked in through the large, double doors, a strong, musky odor hit our nostrils. Several casement windows let in a little light – only a little though, because they were dirty. Jacob maneuvered us through an initial half-dark section towards one of the wooden barricaded areas and peered over the edge.

“Well, here we are then,” Daniel said, following close at his heels and scrutinizing the pen as well, “and look at all the lambs.”

At this point Samwell breathed a huge sigh. It touched the wainscoting and landed on all the bewildered sheep huddled together in a corner.

“They are a silly-looking bunch,” Jacob commented, “and which do you suppose might suckle your little ewe lamb?”

“Not silly, Jacob,” Samwell countered. “Bright eyes and white wool. Beautiful.”

We were now, all four of us, standing next to one of the several sheep folds. It was dull in the large shed. Hay lay strewn about and we could hear pigeons cooing somewhere in the distance. At this juncture one of the mother ewes stood up and curiously approached us.

“Maybe that’s the mother,” Samwell whispered. “Maybe she’s ….”

The barn door opened and shut behind us with a bang, all within the space of a second. Samwell’s murmur dropped into the straw. Even as he stopped talking, two rough hands gripped his shoulders, turning him one hundred and eighty degrees.

“And what would you be doing in my barn, young scallywag!” It was not so much a question as it was an accusation.

Remembering this, I am still amazed that the enmity of the tone had not phased Samwell’s resolve to help the little being snuggling within his coat. “I ask for help, Ryker.”

The words fell thick and Samwell’s tongue threatened to leave the confines of his mouth. It appeared that Ryker was somewhat taken aback by this reply, for he did not immediately strike the boy as I had thought he was about to do. But then, both Jacob and Daniel were imposingly present and both, I am proud and relieved to say, stayed by the boy’s side.

“I ask for help, Ryker,” Samwell repeated, rather louder this time, his arms caressing the lamb. ” I have a new lamb. It needs milk. You have ….”

“I have nothing which you can have, Boy,” Ryker retorted.

Then he suddenly reached down into Samwell’s coat. Drawing out the small, white body hidden within that coat, he cruelly mounted it hard on the wooden gate post. The diminutive, woolly bit of lamb blatted softly. Then it piteously gasped, expiring before our eyes. Samwell fell down to his knees.

“God loves all His lambs,” he said, holding up his right hand.

Fixing his gaze on the crucified lamb, he wept. He cried as the lamb had cried, and his round head lolled on his chest. Jacob touched my shoulder and indicated that we should leave.

“The lamb’s dead anyhow,” he whispered, “and you can’t do any good here any longer. Take the lad and go.”

I bent over and took Samwell by his right upheld hand. He gazed up at me, but did not see me as his eyes were filled with tears.

“Come on, Samwell,” I urged, “let’s go home.”

And so we did. We trudged through the now foggy early evening and made for the Sparrow farm, Samwell coughing wretchedly all the way.

CHAPTER 6 – The richest man in Harston

After I had entrusted Samwell to the care of Sarah, who was quite anxious as to his shortness of breath, I set out for my own home hoping that Cora would have some hot soup and fresh bread ready, for I was cold and hungry. About an hour had transpired since Samwell’s encounter with Ryker Bitter. As I neared Hillbrook Street, a man passed me riding a horse at breakneck speed, galloping past as if his life depended on it. I was home shortly thereafter, and had my mind fixed to speak to my mother and father about what had happened.

However, I found Mr. Solls, our pastor, in the living room and did not think it proper to relate the incident in front of him. My mother served me bread and soup in front of the warmth of the hearth and I half-listened to Father and Mr. Solls discuss doctrine. I confess I almost fell asleep after I ate, so pleasantly warm was I and so worn out with the afternoon were it not for a sudden loud knocking at the door.

“Open up. I must speak with Mr. Solls.”

We could all hear the voice, an insistent voice, abrasive and intruding. Cora answered the door. Not easily put out, she nevertheless looked out of sorts and rather shaken when she announced that Ryker Bitter was insistent upon seeing Mr. Solls.

“Well, let the man in,” Father said, “for Mr. Solls is here and our guest.”

Cora did not have to walk back into the hallway to issue the invitation, for Ryker Bitter had pushed his way through the study doorway and was standing larger than life in front of all four of us – Father, Mother, myself and Mr. Solls.

“I need to ….” he began, stuttering and stammering, while wobbling on his feet, black riding boots encrusted with mud.

“What need you to do?” Father mildly remarked, ignoring Ryker’s obvious confusion and agitation.

“I need to speak with Mr. Solls, but,” Ryker jabbered, “I can speak freely in front of you all, I think. Yes, I think that I can.”

“Well, Man,” Father said, “out with it. What is it that has you so riled up?”

“I will die tonight,” Ryker babbled, drooling somewhat out of the corners of his mouth, and I wondered that the man was presently so obviously inattentive to his person, as he had so often made fun of Samwell’s outward appearance.

“Die?” Mr. Solls and Mother spoke simultaneously.

“Yes, I will die.”

“How do you know that?” This time it was Father who questioned.

“I heard God speak. Indeed, He spoke directly to me saying that I would die. And I must prepare.”

“Ryker,” this time Father spoke a little more gently, “sit down, Man! Sit down. I think you have had a dream or perhaps you’ve been drinking?” He got up and guided Ryker towards one of the cushioned armchairs, pushing him down forcibly. Appearing distracted, looking at us but not really seeing us, Ryker sat down shakily. His leather riding boots left soiled imprints on Mother’s carpet. She did not appear to notice but was staring at Ryker with great eyes.

“There was a voice,” Ryker rasped out, “and it came to me from the roof of the barn. It was a great voice, a hollow voice, and it said, ‘Ryker, tonight the richest person in Harston will die.'”

“What …?” Mother began, only to stop for she did not know what to say.

Indeed, I wouldn’t have known how to reply to such a statement either.

“I must know,” Ryker’s hoarse voice went on, “I must know how to die. You see, I don’t know how to do that.”

Mr. Solls eyed Father who raised his eyebrows and shrugged slightly. “Mr. Bitter,” Mr. Solls began, “it’s a strange tale you tell, and I must confess I rather doubt ….”

“Doubt!” Ryker wailed, and surely wailing was the correct description of the eerie sound he brought forth, “I heard the voice, Man, I heard it. It surely was meant for me.”

There was quiet for a moment, aside from the fact that Ryker was breathing hard and was hitting the knuckles of his hands on the supporting wooden sides of the chair in which he was sitting.

“Well,” Mother said purposefully, standing up suddenly, “I think I will go and get you a hot toddy, Ryker. It will relax you some.” She was out of the room in an eyeblink. Ryker made no comment.

Father coughed and Mr. Solls seemed rather uncomfortable. This seemed rather strange to me as Mr. Solls, being the pastor of our church, of all people should be comfortable with talking about God and about death. As I was thinking this, he got up, walked over to Ryker’s chair and knelt down on the carpet by his feet.

“Ryker,” he began, leaving off the Mister he had used previously, and repeating, “Ryker, you must tell us a little more. We’d like to help you but perhaps it would be beneficial if you told us exactly what happened.” Mr. Solls was in possession of a liquid voice, a fluid voice as it were, and it was soothing.

Ryker sighed deeply. “Very well,” he conceded, “I will tell you. I was in the barn, you see. That young scallywag, Samwell, he’d been by together with … well, together with your son, Mr. Harrison ….”

I exhaled rather noisily at this point although I hadn’t notice that I had been holding my breath. Ryker looked over.

“Yes, I see you Ryle, and you were there.”

I nodded, not knowing what to say. The fact is that I dearly wanted to alert Father to the truth, to the fact that Ryker had been cruel to Samwell and had killed a little lamb. But I could not formulate the words.

“Well, the young boy irritated me. Always pushy that one, with his big smiles and ….”

“I don’t think I want to hear any sort of blather about Samwell,” Father interrupted. “He is as dear to me as my own son.”

Ryker went on, almost as if he had not heard Father. “Well, after Samwell and young Harrison here left, I checked around the barn. Wanted to make sure that there was nothing missing, nothing broken and that everything was in place…. Well, it was then that I heard a breathing, a loud sort of breathing. It seemed to be coming from the center of the barn roof ¬– thereabouts anyway. I looked up to see if there were pigeons flying about or if there was a thatching problem, but there’s dim lighting in the place and it’s been a dull day, you understand, and I could see nothing amiss. And then,” and here Ryker’s voice changed, “then a voice began. ‘Ryker’ it said, and very loudly too, ‘Ryker, tonight the richest person in Harston will die.'”

Mr. Solls, who was still kneeling by the armchair, took Ryker’s right hand between his own hands. “Suppose it were true, Ryker,” he posed, “suppose that you were to die tonight. What then would happen to your soul? It’s not a bad thing for you, and for all of us, to think on. That is the truth.”

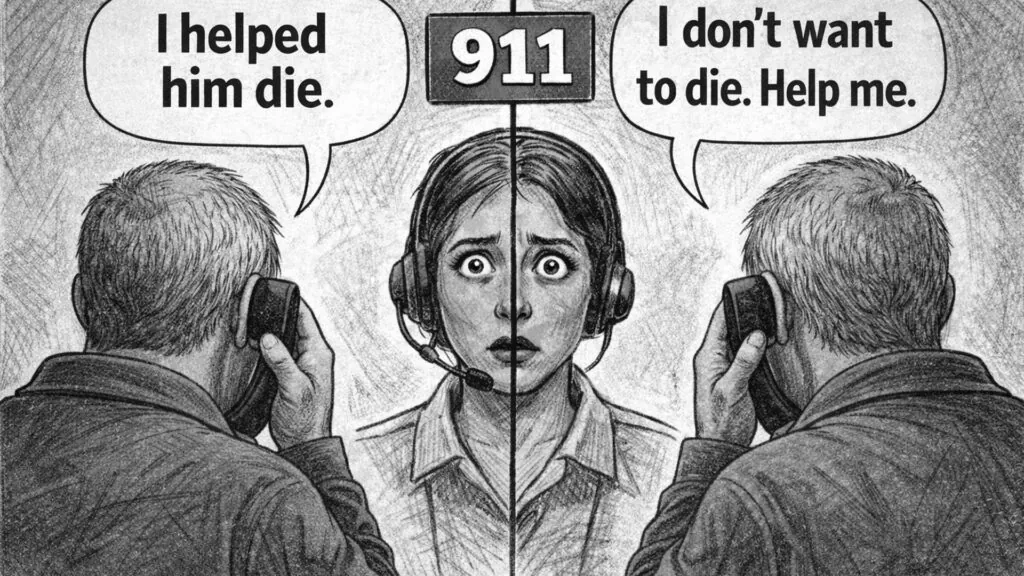

He got no further. Ryker pulled his hand away and held it up in the air even as Samwell had held his hand up. I reflected on how strange that was. Two hands and two thoughts. For even as Ryker’s eyes bulged with fear and panic, he also blurted out five words. “And what is truth exactly?”

His words hung in the air even as the lamb had hung on the wooden gate post.

“Well,” Mr. Solls responded, not exactly answering Ryker’s question directly, but raising a good point nevertheless, “to think on death is healthy because it reminds us that sooner or later we shall all meet our Maker, Ryker.”

Ryker’s hand fell down and he slumped over. “There is no cure for it. I am undoubtedly the richest person in town. So I shall die. I know it.”

Mother slipped into the room again. She carried a cup which, as she told us later, contained a sleeping draught. She passed it to Mr. Solls, who gently, with the assistance of Father, helped Ryker sit up. He drank the liquid almost greedily and then leaned his head against the back of the chair and closed his eyes. Within minutes he was asleep.

*****

It was only an hour or so later that the doorbell rang again. Ryker was still sleeping. The lamp lights had been turned off around him and there was darkness where his chair stood. This time Cora let Sam Sparrow into the room – Sam, the father of Samwell and husband of Sarah.

“I came to tell you,” he grieved, and his voice fell onto the soiled imprints that Ryker’s boots had left on the carpet, “that our Samwell’s years have come to an end like a sigh. The favor of the Lord rested upon him. His wheel has broken at the cistern and his spirit has returned to God Who gave it.”

All three pictures are by Havilah Farenhorst, a granddaughter of the author.