Is infant baptism simply a Reformed peculiarity that ought to be jettisoned in the name of Biblical faithfulness and unity with fellow Christians? What are the grounds for infant baptism?!

*****

Among the readership of this magazine, it’s standard fare that parents will have their infants baptized. However, around us are countless Christians who don’t think the Bible teaches infant baptism. Then when our younger and not so young members meet these other Christians, and end up talking about baptism, questions arise about whether the Lord actually wants the newborns of the congregation baptized.

It might be pointed out that there is no text in the New Testament commanding the baptism of children. In fact, the New Testament does not even have examples of children actually being baptized!

So our questions become bigger: is infant baptism simply a denominational peculiarity that ought to be jettisoned in the name of Biblical faithfulness and unity with fellow Christians? And if not, what are the grounds for infant baptism?

Key question #1: Is there one Bible or two?

It is true that the New Testament nowhere contains a text explicitly commanding the baptism of children. That there are no instances of children being baptized is debatable, but let’s set that aside for the moment. The key question that needs to be asked now is, why would we even expect the New Testament to have such a command?

Funny comment, you say? Well, foundational to the whole discussion on infant baptism is whether the New Testament is the “real” Bible, a book to be read on its own, or is the New Testament to be read in the light of the Old Testament, with both testaments together making up the “real” Bible? In other words, is there continuity between the Old Testament and New, or discontinuity?

Many Christian will, regularly, contrast the New Testament with the Old. The God of the Old Testament is said to be stern and demanding, while the God of the New Testament is loving and merciful. The God of the Old Testament insists on law, while the God of the New Testament gives His Son for our sins. In the Old Testament, He had a covenant rooted in blood, one made even with children, but in the New Testament, his promises are for those who believe in Him – something little children do not do.

Another result of the contrast between Old and New is that markedly more sermons are preached in North America today from New Testament texts than from the Old Testament…even though the Old Testament numbers twice as many pages as the New Testament. Though the Old Testament remains in the Bibles circulating in our society, it’s the New Testament that ends up dog-eared and marked. And since the New Testament does not explicitly speak of infant baptism, this long-held practice of the church falls into disrepute.

Is it indeed true, though, that the message of the Old Testament is somehow different from that of the New Testament?

No. Consider the following passages:

- Jesus says to the Jews: “You diligently study the Scriptures because you think that by them you possess eternal life. These are the Scriptures that testify about Me” (John 5:39). In this passage the phrase “the Scriptures” can only be a reference to the Old Testament since the New Testament was not yet written in the days of Jesus’ earthly sojourn. The topic of the Old Testament Scriptures, says Jesus, is none other than Jesus Christ Himself. Jesus’ teaching was not different from the teaching of the Old Testament, but was the instruction of the Old Testament made plain.

- After His resurrection from the dead, Jesus joined the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. In response to their disappointment at Jesus’ crucifixion and their confusion about the empty tomb, “He said to them, ‘How foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Did not the Christ have to suffer these things and then enter His glory?’ And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, He explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning Himself” (Luke 24:25-27). Jesus’ reference to “Moses and all the Prophets” is obviously the Old Testament Scriptures. According to Him, the message of the Old Testament is none other than that “the Christ had to suffer these things” – and the disciples should have known that. He went on to make plain to these disciples just how the Old Testament spoke of Jesus Christ. It does not go too far to insist that Jesus’ opening of the Old Testament to these two disciples trickled down to all the apostles and so colored the way the disciples later used the Old Testament in the sermons mentioned in the book of Acts and in the letters they wrote to the churches.

- So Peter in his Pentecost sermon quotes Psalm 16, where David said: “My body also will live in hope, because You will not abandon me to the grave….” Then Peter adds this explanation: “Seeing what was ahead, [David] spoke of the resurrection of the Christ, that He was not abandoned to the grave, nor did His body see decay” (Acts 2:26,27,31). Peter realized: the subject of the Old Testament is the same as the subject of the New Testament; both speak of Jesus Christ. (See also Acts 8:32-35.)

- The apostle to the Hebrews tells his readers that: “Christ is the mediator of a new covenant, that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance – now that He has died as a ransom to set them free from the sins committed under the first covenant” (Heb. 9:15). The apostle’s closing words in this quote are intriguing. The “sins committed under the first covenant” are the sins of the Old Testament dispensation, sins committed while the sacrificial system of the Mosaic Law was in effect. Yet how could those sins be forgiven? The apostle insists that it is Christ’s death that sets the Old Testament people free from their sins! How that’s so? That’s so because the sacrifices of the Mosaic Law foreshadowed the sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross. The blood of goats and calves did not by itself wash away Israel’s sins, but that blood directed the Old Testament sinner to focus on the coming sacrifice of the Lamb of God on Calvary.

The point is this: the essential message of the Old Testament is identical to the essential message of the New Testament. Holy God has a relation with sinners in both the Old Testament dispensation as well as in the New Testament dispensation. This relation is possible in the Old as well as in the New Testament only because of the blood of Jesus Christ. The Old Testament looks forward to the Christ who will come (and by His coming sacrifice believing sinners were reconciled to God), while the New Testament looks back on the Christ who has come (and by His completed sacrifice believing sinners are reconciled to God). There is an essential continuity between these two Testaments on the subject of how God relates to sinners. Abraham and Moses and David and the rest of the Old Testament saints were Christians as much as Paul and Augustine and Calvin and the rest of the New Testament saints were and are Christians.

Not new, so much as renewed

Perhaps you will counter that the New Testament is surely called “new” for a reason. Did Jeremiah not prophesy of a “new covenant”? Indeed, he did. “‘The time is coming,’ declares the LORD, ‘when I will make a new covenant with the house of Judah…” (Jer. 31:31).

As a result we read repeatedly in the “New” Testament of a “new covenant” (1 Cor. 11:25; Heb. 9:15). But the word “new” is not to be contrasted with “old” in the sense we use it to say our “new” car is a totally new machine from our “old” one.

The same word that’s translated in Jeremiah 31 as “new” appears in Psalm 104:30 to describe springtime: “When You send your Spirit, …You renew the face of the earth.”

The same word appears also in 2 Chronicles 24:4 to describe Joash’s plan “to restore the temple of the LORD.”

Because of Israel’s hardness of heart in their service to God, the Lord promised through Jeremiah to make a “new covenant.” Yet this is not one that is essentially different from the covenant God made with their fathers when He took them out of Egypt, but one that reaches deeper into His people’s heart. For this time “I will put My law in their minds, and write in on their hearts. I will be their God, and they shall be My people” (Jer. 31:33). Note those closing words: this covenant is described with the same words as God used for His relation with Abraham and with Moses so long ago (Gen. 17:7; Ex. 20:2). It’s the same covenant – “I will be their God” – yet “new” in that it’s renewed, refreshed, deepened.

Just one people

I will, for just a moment longer, belabor this unity between the Old Testament and the New Testament because it is a most vital point.

Writing to Christians of Rome, Paul claims that Abraham “is the father of all who believe” (Rom. 4:11) and the context makes clear that the word “all” refers to both the Jew (of the Old Testament) as well as the Gentile (of the New Testament dispensation). Paul adds,

“Therefore, the promise comes by faith so that it may be by grace and may be guaranteed to all Abraham’s offspring – not only to those who are of the law but also to those who are of the faith of Abraham. He is the father of us all” (Rom. 4:16).

We need to understand his point here. The Christians of Rome had no Jewish blood in them and so were not children of Abraham by birth. Yet Paul insists that this foundational figure of the Old Testament was “the father of us all,” Jews and Romans alike. That is: Old Testament believers and New Testament believers have one father, Abraham.

How are we to understand this? The apostle wants us to think of a tree. Because so many Jews rejected Jesus Christ as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy, God (says Paul) broke those fruitless branches off the tree of Abraham. But since God wanted His tree to bear fruit, He in mercy grafted new branches – Gentiles – into this same tree. These Gentiles then are as much children of Abraham as were their believing brethren of the Old Testament (see Rom. 11:17-24).

There is, then, one tree-of-faith spanning both testaments, a single tree rooted in Abraham, sustained by faith in Jesus Christ, and bearing the fruit of the Holy Spirit. This is why Paul can elsewhere say that “there is one body and one Spirit …, one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all” (Eph. 4:4-6). The faith of the Old Testament is not different from the faith of the New Testament, no more than the God of the Old Testament is different from the God of the New Testament. There is a profound and essential unity (and hence continuity) between Old Testament and New.

Key question #2: Short of an explicit command, why would we presume children would now be excluded?

But how does this touch upon infant baptism?

Like this: given the continuity between the Old Testament and the New, one must expect God’s pattern of dealing with sinners in the New Testament to be same as His pattern of dealing with them was in the Old Testament… unless God explicitly tells us of a change.

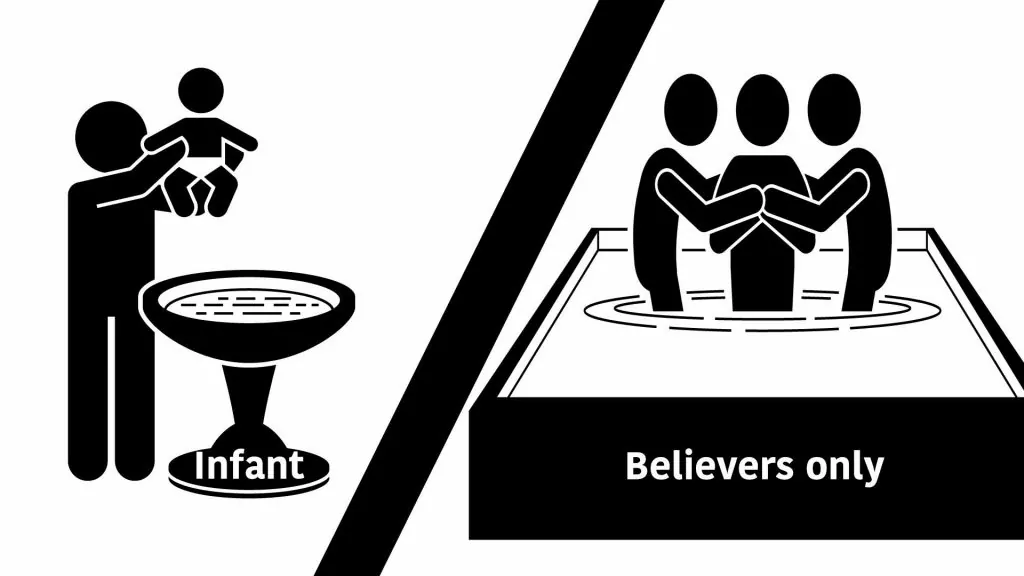

In relation to the sign of the covenant (circumcision in the Old Testament) He has in fact plainly told us of a change for the New Testament dispensation. But there is no explicit instruction in the New Testament indicating that His inclusion of children in the covenant in the Old Testament is replaced by a different pattern in the New Testament.

That is why I asked at the start whether we need an explicit command to baptize infants before we can adopt the practice. Insisting on such a command presumes that the New Testament is not built on the foundation of the Old Testament. It presumes that in the New Testament dispensation God’s covenant with sinners as it operated in the Old Testament was torn up and an entirely new manner of relating with sinners was developed for the New Testament dispensation.

Yet that premise turns out to be false; on the subject of how God deals with sinners there is between Old Testament and New not discontinuity but essential continuity.

Key question #3: How did God treat the children in the Old Covenant?

Now let’s consider what place children had in the Old Testament and what that says about children in the New.

Noah’s family

Today’s western society looks at persons primarily as individuals, and only secondarily as members of families. The Old Testament picture is different. In the days of Noah, God determined to destroy all mankind, but left one exception: “Noah found favor in the eyes of the Lord” (Gen. 6:8).

Yet once the ark was complete, the Lord instructed not just the single righteous individual Noah to “go into the ark,” but his “whole family” was to join him (Gen. 7:1). The phrase “your whole family” included Noah’s wife, his three sons, and their wives (7:13). Please note: because of the righteousness of the one man, God had mercy on his entire family.

That pattern jumps into its own in God’s covenant with Abraham. God told him,

“I will establish My covenant as an everlasting covenant between Me and you and your descendants after you for the generations to come, to be your God and the God of your descendants after you” (Gen. 17:7).

God’s attention was not directed to the individual, but to the family represented in the person of Abraham. As a result, “on that very day Abraham took his son Ishmael and all those born in his household or bought with his money, every male in his household, and circumcised them, as God told him” (Gen. 17:23). “Every male in his household” included “the 318 trained men born in his household” with whom Abraham pursued the four kings who had captured his nephew Lot (Gen. 14). That these 318 were also circumcised was, the text says, “as God told him” – and the point is that with His covenant with Abraham God’s goodness touched all those whom He entrusted into Abraham’s care. The point is that God does not work with isolated individuals, but works in families.

Israel

At Mt Sinai the Lord God renewed His covenant with Israel with these words, “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery” (Ex. 20:2). Yet what was the makeup of the people congregated at the foot of the mountain? Was the content of God’s word here valid only for the adults? Obviously not, for in this same conversation the Lord addressed specifically the children also; He told them in the fifth commandment to “honor your father and your mother” (vs 12). Here is the same point: God deals with His people in families!

When the Lord repeated His covenant with Israel one final time before they crossed the Jordan to enter the Promised Land, He spoke these telling words,

“Carefully follow the terms of this covenant, so that you may prosper in everything you do. All of you are standing today in the presence of the LORD your God – your leaders and chief men, your elders and officials, and all the other men of Israel, together with your children and your wives, and the aliens living in your camps who chop your wood and carry your water. You are standing here in order to enter into a covenant with the LORD your God, a covenant the LORD is making with you this day and sealing with an oath, to confirm you this day as his people, that he may be your God as he promised you and as he swore to your fathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. I am making this covenant, with its oath, not only with you who are standing here with us today in the presence of the LORD our God but also with those who are not here today” (Deut. 29:9-15).

Notice that the children and the wives, and even the aliens in the camp, are included in the crowd of those with whom the Lord made His covenant. More, that covenant is made not only with those who were present “but also with those who are not here today.” That last phrase is not a reference to the mothers or children who stayed behind in the tent, for they were already included in the earlier reference to “your children and your wives.” That phrase is rather a reference to the children yet unborn, those of coming generations (see Acts 2:39). God relates to His people not as lone individuals but as families in untold generations.

So, it is no surprise to hear the prophets speak about future generations. Isaiah quotes the Lord as saying:

“My Spirit, who is on you, and my words that I have put in your mouth will not depart from your mouth, or from the mouths of your children, or from the mouths of their descendants from this time on and forever” (Is. 59:21).

Ezekiel shares the perspective: “They will live in the land I gave to My servant Jacob, the land where your fathers lived. They and their children and their children’s children will live there forever” (Eze. 37:25).

Key question #4: How does God treat children in the New Testament?

Jesus’ response to His disciples is then predictable. When His disciples sought to hinder mothers’ efforts to bring their children to Him, Jesus was “indignant” – literally “livid” – and told His disciples, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these” (Mark 10:14). What made Him so indignant? He was upset with His disciples because the Lord God had sent His Son into the world to “save His people from their sins” (Matt. 1:21), and “His people” includes – according to Old Testament pattern – the children of the covenant. The little ones whom the mothers were bringing to Jesus were not little Romans or little Moabites, but little Israelites, covenant children all. That’s the reason why Jesus “took the children in His arms, put His hands on them and blessed them” (Mark 10:16). If His Father’s reach in the Old Testament included the children in Israel, the Son’s reach was not allowed to be any less.

…for you and for your children…

Peter’s words on the day of Pentecost are consistent with the picture that arises from the Old Testament. It was manifestly the adults of Jerusalem that demanded the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth, and also the adults that recognized their guilt and asked the disciples what they had to do. Peter’s answer is instructive: “Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38).

But notice how Peter formulates his incentive to their repenting: for “the promise is for you and your children and for all who are far off – for all whom the Lord our God will call” (vs 39). What did the Jews understand by the word “promise”? Steeped as they were in Old Testament thinking, the reference to “the promise” that was for them and their children was plainly the content of God’s covenant with Israel: I will be your God.

Notice that Peter does not limit the covenantal promise to the generation standing before him, nor to that generation plus their children at home, but he includes generations still unborn. The generation standing before him needs to repent on grounds that God has made His covenant with them, and needs to repent also on grounds that God has made His covenant with their children after them (including the unborn) – and so those children need God-fearing parents to teach them the Lord’s way.

Here again is nothing of the individualism so rife in our modern western society, but instead a deep awareness that God relates to His people in the generations.

Infant baptisms in the New Testament?

If, then, the New Testament shows that children belong to God just as much as they did in the Old Testament – and there they were circumcised – and if there’s an essential unity and continuity between the Old Testament and the New, we would expect to find in the New Testament instances of infants being baptized just as Ishmael and Isaac were circumcised. Is such evidence available? We’re told it’s not. But consider the following:

- At the end of his visit with Cornelius, Peter asked, “Can anyone keep these people from being baptized…?” Since there were no objections “he ordered that they be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ” (Acts 10:47-48). Who exactly made up the crowd that was baptized? The crowd is described in verse 24 as Cornelius himself and “his relatives and close friends.” Does this include children? At a minimum it certainly does not exclude children.

- In response to hearing the apostle’s preaching, Lydia came to faith. The Holy Spirit records the event as follows: “The Lord opened her heart to respond to Paul’s message. When she and the members of her household were baptized, she invited us to her home” (Acts 16:14-15). Notice the formulation: the Lord tells us of one believer and of multiple baptisms, all of them within her household. It’s the identical pattern as we discovered with Abraham. Were children baptized with Lydia? The text certainly does not exclude children. On the contrary, we may safely say that if Lydia had children in her household, they too were baptized.

- After the earthquake that shook the Philippian jail, the rattled jailer fell trembling before Paul and Silas to ask his desperate question: “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” Their answer: “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved – you and your household” (Acts 16:30-31). Notice how the faith of the one man touches his whole household. As a result, “he and all his family were baptized” (Acts 16:33). In our translation the passage adds that “he was filled with joy because he had come to believe in God – he and his whole family” (vs. 34). But the Greek isn’t so explicit about “his whole family” having believed. The Greek very much places the onus on the jailer alone, and (as in vs. 31) the family benefits from his repentance. Were children baptized with the jailer? The passage allows for only one conclusion: if he had children, they most certainly were baptized too.

We recognize in all these passages the Old Testament pattern of God dealing not with individuals but with families – and His approach to the family is determined by the spirituality of the family’s head. As a result, we certainly cannot insist that the New Testament knows nothing of infant baptism.

This becomes all the clearer when we recognize that the terms rendered in the above passages as “household” or “family” appear elsewhere in Scripture with obvious inclusion of little children.

Jacob laments that if the Canaanites attack “I and my household will be destroyed” (Gen. 34:30) – and he’s surely not suggesting that the enemy will spare the little ones in his tents, be they his own (grand)children or the offspring of his servants.

Moses reminded Israel that the Lord “sent miraculous signs and wonders… upon Egypt and Pharaoh and his whole household” (Deut. 6:22), and we understand well that the infants of Egypt were as discomfited by the plagues of frogs and lice and darkness as the older of the population.

See further Gen. 7:1; 12:17; 18:19; 36:6; 50:7f; Ex. 1:1; Josh. 24:15 and so many more. The term “household” in Scripture certainly includes children.

Finally, if the point is still raised that the New Testament only explicitly mentions adults being baptized, let the reader recall that the apostles were missionaries engaged in mission work. Even today infant baptism on a mission field is relatively uncommon on the simple ground that mission work is directed at adults. And when under God’s blessing the adults come to faith, the household is baptized.

Conclusion

The conclusion, then, is evident: though there is no explicit mention of an infant being baptized, the New Testament – in line with God’s Old Testament revelation – both knows and requires the baptism of little children.

Rev. Clarence Bouwman is the Minister Emeritus for the Smithville Canadian Reformed Church.