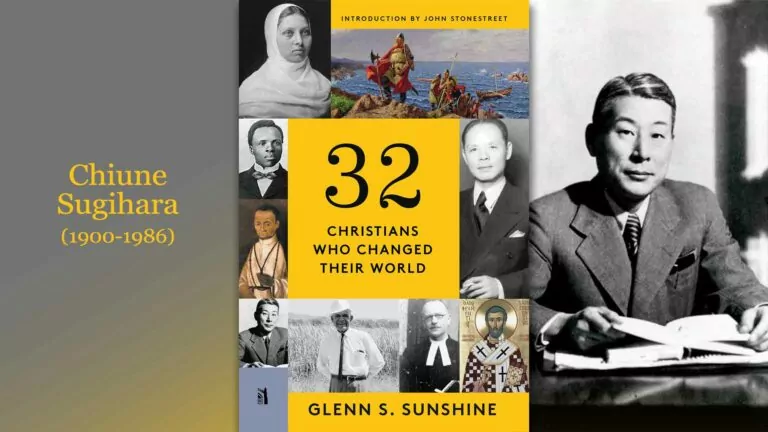

This is a chapter from Dr. Glenn Sunshine’s “32 Christians Who Changed Their World” and is reprinted here with permission of the publisher.

*****

In the mid- to late-1800s, Japan ended its long centuries of isolationism and opened to the outside world. Knowing the de facto loss of sovereignty in China to Western nations in the aftermath of the Opium Wars, Japan decided not to give the industrial powers an excuse to do the same to their country. They rapidly industrialized and patterned their government on superficially Western lines while preserving the existing power structure.

Then they started building their own empire, starting with taking Chinese cities following the model of the Western powers, and then moving on to take Korea and Manchuria (northeast China). After World War I, the Japanese continued to build their empire in China as well as setting their sights on other areas in the Pacific. Given that Britain, France, and the Netherlands all had interests in the western Pacific, the Japanese allied with Hitler on the principle that the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Although the Japanese had a culture of obedience to superiors and especially to the emperor, at least one man and his wife gave their first allegiance to God over the empire. His name was Chiune Sugihara.

Sugihara was born into a middle-class family in Gifu Prefecture in Japan. His father, who was a physician, intended Chiune to go to medical school. Chiune had other plans, however: he intentionally failed his entrance exams by writing only his name on the tests. Instead of medical schools, he entered Waseda University in 1918, where he majored in English. While there, he joined Yuai Gakusha, a Christian fraternity.

In 1919, he passed the Foreign Ministry Scholarship exam and was soon sent to Harbin, a city in Manchuria, China, to study German and Russian. He graduated in 1924 with honors and was promptly hired by the Foreign Ministry as deputy foreign minister in Manchuria.

During this period, Sugihara joined the Russian Orthodox church and was baptized as Pavlo Sergeivich Sugihara. He married Klaudia Semionova Apollonova, a Russian woman, though they divorced in 1935 before his return to Japan.

While in Harbin, Sugihara was involved in negotiations with the Soviet Union over the Northern Manchuria Railway. Manchuria was under the control of Japan at this time, and Sugihara was disturbed by the poor treatment of the Chinese. He resigned in protest and returned to Japan.

Back home, Sugihara married Yukiko Kikuchi. The two would have four children. He was sent as a translator for the Japanese legation in Helsinki, Finland, in 1938. In March 1939, he was appointed vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, where he was expected to report on Soviet troop movements. What he actually did there, however, was far more important.

Kaunas was full of Polish Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis. One day, Sugihara was in a gourmet food shop. An eleven-year-old boy named Solly Ganor, the nephew of the shop’s owner, was also there. His parents were Russian Jewish menshevik refugees. Solly was concerned about the fate of Polish Jews and had given all of his money and Hanukah gelt (money given as gifts during Hanukah) to aid them. But then he heard that a new Laurel and Hardy movie was showing in town, and so he went to visit his aunt Anushka in hopes of getting a lit (Lithuanian dollar) to go to the movie.

Sugihara overheard Solly and offered the boy money. Solly, who had never seen an Asian before, did not know what to make of this offer, so he mumbled that he couldn’t accept money from strangers. Sugihara said that he should consider him his uncle for the holiday, and since that made him family, it would be alright to accept the money. Solly looked into the stranger’s kind eyes and impulsively said that if he was his uncle, he should come to the family’s celebration of the first night of Hanukah, 1939.

Sugihara and his wife were delighted to accept, and so they attended their first Jewish Hanukah celebration. They were warmly welcomed and long remembered the cakes, cookies, and desserts they had at the party.

Most of the evening was a warm celebration of the holiday. But Solly’s family was housing a Polish refugee named Mr. Rosenblatt. As the evening wore on, he talked about the slaughter of the Jews in Poland under the Nazis. He tearfully told of the bombing of his house, which killed his wife and children. His story had a tremendous impact on everyone, especially the Sugiharas.

The next day, Solly and his father visited Sugihara at the consulate. They found him phoning the Russians asking for visas to allow Jews to cross the border.

In summer 1940, the Soviets formally annexed Lithuania. The Jews were desperate to get exit visas to leave the country, and in July Sugihara was awakened by a crowd of hundreds of Jewish refugees standing outside the consulate. Sugihara wired Japan three times asking for permission to issue transit visas for the Jews. (A transit visa would allow the Jews to travel through Japan on their way to somewhere else.) Three times he was told not to issue visas unless they also had visas to go to another country.

Sugihara was in a difficult situation: if he issued the visas, he could be fired and disgraced; if he didn’t, the Jews would die. He and Yukiko agreed that they needed to follow their consciences even though they knew it would cost him his position, and the two went to work.

From July 31 to September 4, Sugihara began writing visas by hand at a rate of 300 per day. He did not even stop for meals – he ate sandwiches that Yukiko left for him by his desk. He even made arrangements for the Soviets to transport the Jewish refugees via the Trans-Siberian Railroad (albeit at five times the normal price).

The refugees began to arrive by the thousands begging for visas. When some began to scale the walls of the consulate, Sugihara came out and promised them he would not abandon them.

And he didn’t. When he was forced to leave Kaunas before the consulate was closed, Sugihara spent the entire night before writing visas. Eyewitnesses said that he continued to write them on the train, tossing them out of the windows as he completed them. In the end, he simply signed and sealed blank visas to be filled in later.

As he was on the verge of departing, he said, “Please forgive me. I cannot write any more. I wish you the best.” He bowed deeply to the crowds, and someone called, “Sugihara, we’ll never forget you. I’ll surely see you again.”

No one knows exactly how many visas Sugihara wrote. Not all were used; some people waited until it was too late to leave. Others were for heads of households, so several people would travel under a single visa. The most commonly accepted number is that 6,000-10,000 Jews escaped the Holocaust because of Sugihara’s actions. Today, somewhere between 40,000 and 80,000 people are descendants of the Jews saved by Sugihara.

Many of the refugees joined the Russian Jewish community in Kobe, Japan; others got transit visas organized by the Polish ambassador in Tokyo to a wide range of third countries, including to a Jewish community in Shanghai, China.

The Nazis wanted the Japanese to kill or send back the Jews, but the Japanese ignored their allies. Ironically, Nazi propaganda worked against them here: the Japanese had heard from the Nazis that the Jews were very good with business and finance, and so they thought that having them would be an asset to Japan. The Jews for their part also played up Nazi racism against Asians, which also made the Japanese less inclined to listen to Germany about exterminating the Jews.

Sugihara paid a price for his actions. He was posted to a variety of Eastern European posts during the war and was captured and imprisoned with his family by the Russians for eighteen months. They were released in 1946 and returned to Japan via the Trans-Siberian Railroad. In 1947, the Foreign Ministry asked for his resignation, ostensibly because of post-war downsizing, though some sources have claimed that the Foreign Ministry told them he was forced out because of “that incident” in Lithuania. He lost his youngest son that same year.

Sugihara took a number of menial jobs to support his family. He even resorted to selling light bulbs door to door. Eventually, he was able to use his command of Russian to land a position as an export manager for a Japanese firm in Moscow. He lived there sixteen years, only visiting his family in Japan once or twice a year during that period. He eventually retired to his home in Japan.

After the war, many of the “Sugihara Survivors” tried to locate him, but no one in the Japanese government or the Foreign Ministry seemed to remember him. Finally, in 1968, Joshua Nishri, economic attaché from Israel to Japan and one of the survivors, managed to track him down. All this time Sugihara had no idea whether his actions had saved anyone, and he was surprised and gratified to discover that they had: he felt that if he had saved even one life all his sacrifices would have been worth it.

The following year, he and his family were invited to Israel, and in 1985, Israel named Sugihara one of the Righteous Among the Nations, the highest honor Israel can grant. Sugihara was too ill to attend the ceremony, so Yukiko and their sons accepted the award on his behalf. The family was granted perpetual Israeli citizenship, and one of the sons would eventually graduate from Hebrew University, speaking Hebrew fluently.

Sugihara died the following year. The people of his community in Japan had no idea of what he had done until a delegation from Israel arrived for his funeral.

Sugihara’s actions were clearly inspired by his faith. As he told his wife, it was more important for him to obey God than his government. His decision to aid the refugees was particularly influenced by his reading of the book of Lamentations in the Bible. He was a man of remarkable compassion, humility, courage, and faithfulness in carrying out the work that God had uniquely placed him to do.