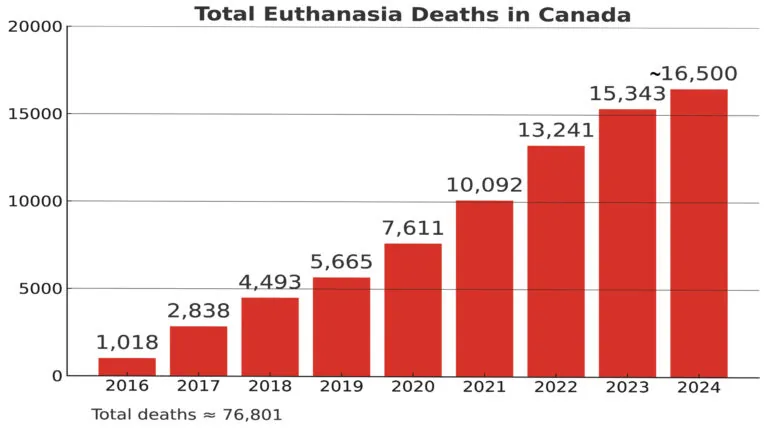

According to calculations from the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition (EPC), as of September this year approximately 90,000 Canadians have been euthanized since this form of homicide was legalized by the federal government in 2016.

Homicide is defined under Section 222 of Canada’s Criminal Code as an act causing the death of a human being.

The staggering number of euthanasia deaths have been steadily increasing, from 1,018 in 2016, to 15,343 confirmed cases in 2023. Based on the reports available for 2024, the EPC projects there were 16,500 euthanasia deaths that year, an increase of 7.5 percent.

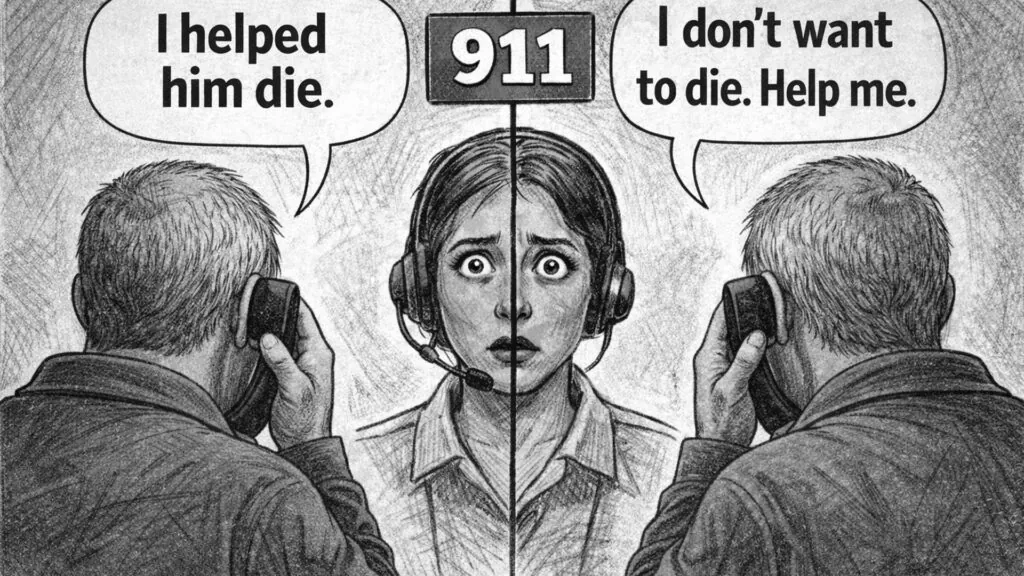

EPC drilled in on BC’s 2024 data and found that 35 percent of the 2,767 euthanasia deaths were approved based on “other conditions.” Of these, 65.9 percent were related to “frailty.” They noted that “frailty” isn’t defined and can encompass euthanasia for a “completed life” – in other words, an elderly person is not sick or dying but simply wants to die.

The increasing numbers, and broad standards for qualifying, are a far cry from what the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Carter v. Canada (2015), when it allowed euthanasia for a competent adult who

“has a grievous and irremediable medical condition (including an illness, disease, or disability) that causes enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual in the circumstances of his or her condition.”

Behind each of these statistics is a human being made in the image of God, many of whom left this earth without hope. As ARPA Canada and others communicated to Parliament and to the courts prior to the legalization of euthanasia, as soon as we remove the sacred line of the Sixth Commandment to not murder, it becomes impossible to maintain any other line. Sure enough, Parliament is now considering further expansions of euthanasia for those whose suffering is solely psychological, as well as for children.