Countering Tim Keller's case for evolution

Examining Tim Keller's white paper Creation, Evolution, and Christian Laypeople

****

Tim Keller’s trusted place among Reformed and Presbyterian folk is well-earned, but not when it comes to his views on evolution. In a discussion paper of some years ago for the Biologos Foundation he provided Reformed scientists with a theologian’s suggestions about how one might apparently help others keep the faith and accept evolution. His 13-page white paper, entitled Creation, Evolution, and Christian Laypeople, has been referenced favorably by scientists and theologians in conservative Reformed churches.(1,2)

In his paper, Keller explores the critical questions of concerned Christians and deals with them head-on. While his forthrightness is commendable, most of his answers are not.

What this debate is not about

It’s important to situate accurately our debate with Keller. The debate between us is not whether the Christian faith and current science (or what is claimed to be science) are irreconcilable, for we all agree that in many respects they are reconcilable while in some respects they are not. The debate, rather, is in what particular respects they are and are not able to be reconciled.

The debate between us is not whether evolution is a defensible worldview that gives us the basis of our views on religion, ethics, human nature, etc. We all agree that it is not the “grand theory/explanation of everything.” We all agree that there is a God and he is the God of the Bible – Triune, sovereign, covenant-making, gracious, atonement-providing, and bringing about a new creation. Nor am I debating whether Keller is an old-earth creationist aka progressive creationist or an evolutionary creationist or a theistic evolutionist. His own position is a bit unclear so I will simply deal with what he has published in this paper.(3)

The debate between us is not whether matter is eternal; whether the universe’s order is by sheer chance; whether humans have no purpose but to propagate their own genes; whether humans are material only; whether human life is no more valuable than bovine, canine, or any other life; whether upon death all personal existence ceases; or whether ethics is at root about the survival of the fittest. We all agree that none of these things are the case – Scripture teaches differently. We are not debating these points.

What it is about – 3 key questions

Our differences emerge in the compatibility of Scripture with biological evolution, namely, whether Scripture has room for the view that humans have a biological ancestry that precedes Adam and Eve. Is this a permissible view?

The first thing to realize as one reads Keller’s paper is its context and purpose: Delivered at the first Biologos “Theology of Celebration” workshop in 2009, Keller lays out 3 concerns that “Christian laypeople” typically express when they are told that God created Adam and Eve by evolutionary biological processes.

Keller advances strategies to help fellow Biologos members allay these fears of Christian laypeople. The context thus is that biological evolution is a permissible view; the scholars just need to figure out how to make it more widely accepted.

Keller deals with the following “three questions of Christian laypeople.”

If God used evolution to create, then we can’t take Genesis 1 literally, and if we can’t do that, why take any other part of the Bible literally?

If biological evolution is true – does that mean that we are just animals driven by our genes and everything about us can be explained by natural selection?

If biological evolution is true and there was no historical Adam and Eve how can we know where sin and suffering came from?

These are excellent questions! But what sort of answers does Keller propose?

Q1. IF EVOLUTION IS TRUE, CAN WE TAKE GENESIS 1 LITERALLY?

Keller’s first question is, “If God used evolution to create, then we can’t take Genesis 1 literally, and if we can’t do that, why take any other part of the Bible literally?” Keller’s short answer is,

The way to respect the authority of the Biblical writers is to take them as they want to be taken. Sometimes they want to be taken literally, sometimes they don’t. We must listen to them, not impose our thinking or agenda on them.

At first glance this is a solid answer – the Bible has authority! But Keller has more to say.

Genre and intent

He expands upon his answer first by delving into the genre of Genesis 1 because “the way to discern how an author wants to be read is to distinguish what genre the writer is using.”

“How an author wants to be read” is a bit ambiguous, but I’ll take it to refer to authorial intent – Keller’s point is going to be whether or not the author wants us to read Genesis 1 literally and chronologically. The link he proposes between genre and authorial intent, however, is not straightforward. Someone can use widely differing genres to communicate the same intended message.

Consider this example: If I use poetry to communicate to my wife how much I love her, my intentions are just the same as if I had written it out in a regular sentence or two. I could even send the same message via a syllogism:

All my life I have loved you;

Today is a day of my life;

Therefore I love you today.

Whether poetry or prose or syllogism (or, as my wife would call it, a silly-gism) my message remains the same.

Now it’s true that in poetry I’m more likely to use figures of speech but that doesn’t mean poetry as a genre can’t recount history. See Psalm 78 for a good example of poetry replete with historical truth.

Genre of Genesis 1

Keller next asks what genre Genesis 1 is and starts his answer with the conservative Presbyterian theologian Edward J. Young (1907–1968) who, he says, “admits that Genesis 1 is written in ‘exalted, semi-poetical language.’”

Keller correctly notes the absence of the telltale signs of Hebrew poetry. Yet he also points out the refrains in Genesis 1 such as, “and God saw that it was good,” “God said,” “let there be,” and “and it was so,” and then Keller adds, “Obviously, this is not the way someone writes in response to a simple request to tell what happened.” He completes this part of the arguments with a quotation from John Collins that the genre of Genesis 1 is “what we may call exalted prose narrative. . . by calling it exalted, we are recognizing that we must not impose a ‘literalistic’ hermeneutic on the text.”

Thus this argument is now complete: Keller is saying that the genre of Genesis 1 prohibits us from reading it literally.

Misleading appeal to E. J. Young

However, if we follow the trail via Keller’s footnote to E. J. Young’s, Studies in Genesis One, we discover that Keller sidestepped Young’s real point. Here’s the fuller quote, “Genesis one is written in exalted, semi-poetical language; nevertheless, it is not poetry” (italics added).

Young continued by pointing out what elements of Hebrew poetry are lacking and by urging the reader to compare Job 38:8-11 and Psalm 104:5-9 to Genesis 1 in order to see the obvious differences between a poetic and non-poetic account of the creation. Prior to this paragraph Young had written,

Genesis one is a document sui generis ; its like or equal is not to be found anywhere in the literature of antiquity. And the reason for this is obvious. Genesis one is divine revelation to man concerning the creation of heaven and earth. It does not contain the cosmology of the Hebrews or of Moses. Whatever that cosmology may have been, we do not know . . . Israel, however, was favoured of God in that he gave to her a revelation concerning the creation of heaven and earth, and Genesis one is that revelation.

Young elaborates further,

For this reason we cannot properly speak of the literary genre of Genesis one. It is not a cosmogony , as though it were simply one among many. In the nature of the case a true cosmogony must be a divine revelation. The so-called cosmogonies of the various peoples of antiquity are in reality deformations of the originally revealed truth of creation. There is only one genuine cosmogony, namely, Genesis one, and this account alone gives reliable information as to the origin of the earth (italics added).

With these words of Young guiding our hearts, we turn back to Keller’s statement that it is “obvious” that someone would not compose an account in the exalted style of Genesis 1 “in response to a simple request to tell what happened.”

Really? But what if the things therein described happened exactly in that exalted way? Of course, we are reading “exalted prose” – precisely because the things described are so wonderful! The literary style not only fits but even reflects the miraculous events. God is glorified repeatedly, all the more because it is literally true.

An old canard: Genesis 1 versus Genesis 2

Keller’s second reason – and strongest, he says – why he thinks the author of Genesis 1 didn’t want to be taken literally is based on “a comparison of the order of creative acts in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2.”

This argument is a bit more complicated and deserves closer scrutiny than I will give it here. But the basic point is that Genesis 2:5 apparently speaks about God not putting any vegetation on the earth before there was an atmosphere or rain or a man to till the ground. This, says Keller, is the natural order. Genesis 1 is the unnatural order, so it’s not literal. His argument is an old canard, but really it is a lame duck.

Let’s examine it: Keller says that Genesis 1 has an unnatural order because:

light (created on Day 1) came before light sources (created on Day 4)

vegetation (Day 3) came before an atmosphere and rain (which he says was created on Day 4)

Let’s consider this second point first. Keller reads the text too quickly here, for the separation of waters above and below occurs on Day 2, thus allowing rain before vegetation. And even if there was no rain, a day without light or water wouldn’t kill these plants anyway.

Now regarding the first point, the “light before lightbearers” problem, it might strike us as interesting that God created light on Day 2 before there were any light sources – the sun moon and stars were created on Day 4 – but why should it strike us as a difficulty? God has no need of the sun to make light (Rev. 21:23).

To continue: the order of events in Genesis 2, especially verse 5, is not in the least contrary to Genesis 1. Rather, whereas Genesis 1:1–2:3 refers only to “God” and focuses on the awesome Creator preparing and adorning the earth for man, Genesis 2:4–25 focus on this God as “Yahweh” who lovingly and tenderly creates the man and the woman, prepares a beautiful garden for them, and who thereupon enters into a loving relationship with them. Each chapter makes its own contribution to the story, with chapter 2 doubling back in order to more fully explain the events of the sixth day. This is a common occurrence in Hebrew prose. Further, we can easily fit 2:4–25 chronologically in between 1:26, “Let us make man in our image” and 1:27, “So God created man in his image . . . male and female he created them.”

Finally, Genesis 2:4 begins the first “toledoth” or “generations of” statement, which after this becomes a structural divider in Genesis, occurring nine more times. Young argues that we should translate “toledoth” as “those things which are begotten.” If we follow this suggestion, we see that Genesis 2:4ff tell us about the things begotten of the heavens and the earth, such as the man, who is both earthly (his body) and heavenly (his spirit), or the garden, which is earthly, yet planted by God. When Genesis 2:5 states that “no shrub of the field” had yet grown and “no plant of the field” had yet sprouted, it portrays a barrenness which sets the stage for the fruitful garden (2:8–14) and the fruitful wife (2:18–25). Further, the “shrubs” and “plants” of the field likely point to cultivated plants that require human tending. Adam will be a farmer. If so, the point of 2:5 is not the lack of vegetation altogether, but the lack of certain man-tended kinds, such as those Yahweh God would plant in the Garden of Eden.

Therefore, we ought to conclude the very opposite of Keller. Whereas he argues that we cannot read both chapter 1 and chapter 2 as “straightforward accounts of historical events” and that chapter 2 rather than chapter 1 provides the “natural order,” we most certainly can read both as historical and literal.

Keller pulls together both the genre and the chronology arguments and concludes,

So what does this mean? It means Genesis 1 does not teach us that God made the world in six twenty-four hour days. Of course, it doesn’t teach evolution either . . . However, it does not preclude the possibility of the earth being extremely old.

However, both of Keller’s grounds for not taking Genesis 1 literally have been exposed as weak at best.(4) In contrast, E. J. Young’s strong arguments for the literal, historical reading of Genesis 1, a few of which we reviewed here, remain firmly in place. Exalted prose indeed, and true!

Whose authority?

Before we move on to Keller’s second question, a word about the authority of the text: Keller states that we must “respect the authority of the Biblical writers.” His wording is similar to that of John Walton’s in speeches Walton gave at a conference I attended in September 2015.(5) Walton frequently spoke of “the authority of the text” and stated that it rested in the original meaning “as understood by the people who first received it.”

But missing from both Keller and Walton is the recognition that all Scripture is breathed by God (2 Tim. 3:16) and that therefore the primary author is the Holy Spirit (2 Pet. 1:21). We are not called just to respect the authority of human writers or of the text, but of God himself!

That’s why there are passages of Scripture for which the first intention of the human writer – as far as we can discern it – does not reach as far as the divine intention. (Consider, for example, certain Messianic Psalms such as 2 & 110, or the injunction about the ox not wearing a muzzle as it treads out the grain – Deut. 25:4; cf. 1 Cor. 9:9; 1 Tim. 5:18). In fact, Peter tells us that the Old Testament prophets searched with great care to find out the time and circumstances of the things they prophesied about Christ – implying that the prophecies went beyond the knowledge of the prophets themselves. He adds that these are things into which even angels long to look (1 Pet. 1:10–12). Thus, it’s clear that the primary author of Scripture is the Holy Spirit and that the authority of the text resides in his intentions first of all. This is why one of the primary rules of interpretation is to compare Scripture with Scripture. This book is God’s Word!

Let us take great care in handling the Word of God – greater care than Keller does on this point. And let us conclude that the text of Genesis 1 itself clearly indicates it is to be read literally, historically, and chronologically (Keller, at least, has not proven otherwise).

Q2: IF BIOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IS TRUE, DOES IT EXPLAIN EVERYTHING?

So let us move on to Keller’s second question. This “layperson” question really gets at a problem: “If biological evolution is true, does that mean that we are just animals driven by our genes and everything about us can be explained by natural selection?”

Keller’s provides this short answer, “No. Belief in evolution as a biological process is not the same as belief in evolution as a world-view.”

Two senses of “evolution” – EBP vs. GTE

In explaining this question and his response, Keller distinguishes evolution in two senses.

Evolution as a means God used to create. Or as Keller puts it, “human life was formed through evolutionary biological processes” (EBP).

Evolution “as the explanation for every aspect of human nature,” which he calls the “Grand Theory of Everything” (GTE).

The problem Keller is addressing is that self-described “evolutionary creationists” – such as those at Biologos tend to be – end up hearing the same critique from both creationists and evolutionists: both argue that you can’t hold the theory of biological evolution without at the same time endorsing atheistic evolution as a whole. Essentially both critics assert that evolution is a package – a worldview, a big-picture perspective – and you can’t just isolate one part of it.

Keller suggests to his fellow Biologos members that most Christian laypeople have a difficult time distinguishing EBP from GTE. They have a hard time understanding that it is possible to limit one’s commitment to evolution to “the scientific explorations of the way which – at the level of biology – God has gone about his creating processes” (Keller quoting David Atkinson).

“How can we help them?” Keller asks, for “this is exactly the distinction they must make, or they will never grant the importance of EBP.” He simply states that Christian pastors, theologians and scientists need to keep emphasizing that they are not endorsing evolution as the Grand Theory of Everything.

Keller’s helpful critique of evolution as the Grand Theory of Everything

To support this, Keller provides a brief but helpful analysis, showing that evolution as the Grand Theory of Everything (GTE) is self-refuting. He touches on this in the paper, and expands on it in an online video from which I’ll also quote.

Basically, according to those who hold to evolution as the explanation of everything (GTE), religion came about only because it somehow must have helped our ancestors survive (survival of the fittest). In fact, they say, we all know there’s no God, no heaven, no divine revelation. Such things are false beliefs.

But if that is the case, argues Keller, then natural selection has led our minds to believe false things for the sake of survival. Further, if human minds have almost universally had some kind of belief in God, performed religious practices, and held moral absolutes, and if it’s all actually false, then we can’t be sure about anything our minds tell us, including evolution as the grand theory of everything. Thus, with reference to itself, evolution as the GTE is absurd.

In the online video Keller is dealing with the problem that opponents of Christianity and of religion generally try to “explain it away.” He states,

C.S. Lewis put it this way some years ago, “You can’t go on explaining everything away forever or you will find that you have explained explanation itself away.”

Keller, following Lewis, illustrates “explaining away” with “seeing through” things: A window lets you see through it to something else that is opaque. But if all we had were windows – a wholly transparent world – all would be invisible and in the end you wouldn’t see anything at all. “To see through everything is not to see at all.” How does that apply to our discussion? Keller then shows that many universal claims are self-refuting.

If, as Nietzsche says, all truth claims are really just power grabs, then so is his, so why listen to him? If, as Freud says, all views of God are really just psychological projections to deal with our guilt and insecurity, then so is his view of God, so why listen to him? If, as the evolutionary scientists say, that what my brain tells me about morality and God is not real – it’s just chemical reactions designed to pass on my genetic code – then so is what their brains tell them about the world, so why listen to them? In the end to see through everything is not to see.(7)

As usual, Keller is an insightful apologist for the Christian faith. He helps us oppose evolution as the Grand Theory of Everything.

Just the same, I heard another prominent evolutionary creationist, Denis Alexander, answering questions at a recent conference (2016) and musing about our lack of knowledge as to when “religiosity” first evolved among our ancestors. So, Keller’s helpful critique notwithstanding, at least one of his co-members at Biologos appears to think that religiosity is an evolved trait (or at least allows for this view).

But Keller doesn’t prove that EBP doesn’t lead to GTE

Although I’ve highlighted something helpful in Keller’s white paper, the main point he needed to do was to prove that one’s commitment to the theory of evolutionary biological ancestry for humans (and all other living things) does not entail holding to evolution as the grand theory of everything. He didn’t prove this, and didn’t really make the attempt. He might not have felt the need to, because of the setting in which he spoke – he delivered this speech to Biologos, an organization which is committed to EBP but wants to avoid GTE because the members are Christians.

Nevertheless, this is the real point at issue.

Can and will Christians be able to hold to EBP without moving to GTE?

I seriously doubt that Christians can or will be successful in adopting evolution as EBP while avoiding the trajectory that moves toward evolution as GTE. Here’s why, in short.

It seems to me that as soon as one adopts EBP, the following positions come to be accepted (whether as hypotheses, theories, or firm positions):

Adam and Eve had biological ancestors, from whom they evolved – some sort of chimp-like creatures. These “chimps” in turn had other biological ancestors and relatives, as do all creatures. In fact, there is an entire phylogenetic tree or chain of evolutionary development that begins with the Big Bang. All living things have common ancestry in the simplest living things, such as plants. At some point before that the transition was made from non-living things to the first living cell (some evolutionary creationists assert that God did something supernatural to make the transition from non-living things to living).(8)

Evolving requires deep time. “Multiple lines of converging evidence” apparently tell us the universe is 14.7 billion years old; the earth is about 4.7 billion, life is about 3 billion, and human life is probably about 400,000 years old (these numbers may vary; I happen to think 6-10 thousand is rather ancient as it is!).

Humans do not have souls; they are simply material beings. This is being promoted by Biologos and other theologians and philosophers.(9) Not all evolutionary creationists would agree; some say God gave a soul when he “made” man in his image, others that the soul “emerged” from higher-order brain processes at some point in the evolutionary history.

The world is getting better, on a continual trajectory from chaos to increasing order, or from bad to good to better to best. This creates great difficulties for one’s doctrine of the fall, redemption in Christ, and the radical transition into the new creation.

The earth, as long as it has had animal life, has been filled with violence. Keller admits in his paper how critical this is: “The process of evolution, however, understands violence, predation, and death to be the very engine of how life develops.” This presents enormous difficulty for one’s doctrines of the good initial creation, and the fall into sin.

God must have been more hands-off. The universe’s order arises mainly due to the unfolding of the inherent powers and structures God must have embedded in that initial singularity called the Big Bang. There is a movement toward Deism inherent in the theory. Much of what the Bible ascribes to God’s creating power and wisdom actually belongs to his providential guidance, which itself was probably a rather hands-off thing.

God’s nature needs to be understood differently – particularly his goodness – if creation was “red in tooth and claw” from the beginning.(10)

Scripture needs to be reinterpreted. The authority of God’s Word falls under the axe due to the exegetical gymnastics required to accommodate EBP. Scripture apparently no longer means what it appears to mean. This opens up the reinterpretation of everything in the Bible.

Where is the line between?

In sum, Keller provides a helpful critique of evolution as the Grand Theory of Everything (GTE). However, he fails to demonstrate that holding to evolutionary biological processes (EBP) does not, in itself, open one up to evolution as the GTE, and may in fact ultimately make it impossible to avoid more and more of evolution as the GTE.

This is surely because for the most part evolution as such depends upon atheistic presuppositions. And in fact, it’s actually quite hard to determine just where the line is between evolution as EBP and GTE. I’m afraid that’s a sliding scale, depending upon which scientist or theologian presents his views. Once the camel’s nose is in the tent... you know the rest.

The academic and religious trajectories of scholars who were once orthodox and Reformed shows how hard it is to maintain evolution as EBP only. I’m thinking of such men as Howard Van Till (who is now more of a “free thinker”),(11) Peter Enns (who now only holds to the Apostles’ Creed and treats the Bible as arising from the Israelites, not from God)(12) and Edwin Walhout (who advocated rewriting the doctrines of creation, sin, salvation, and providence).(13)

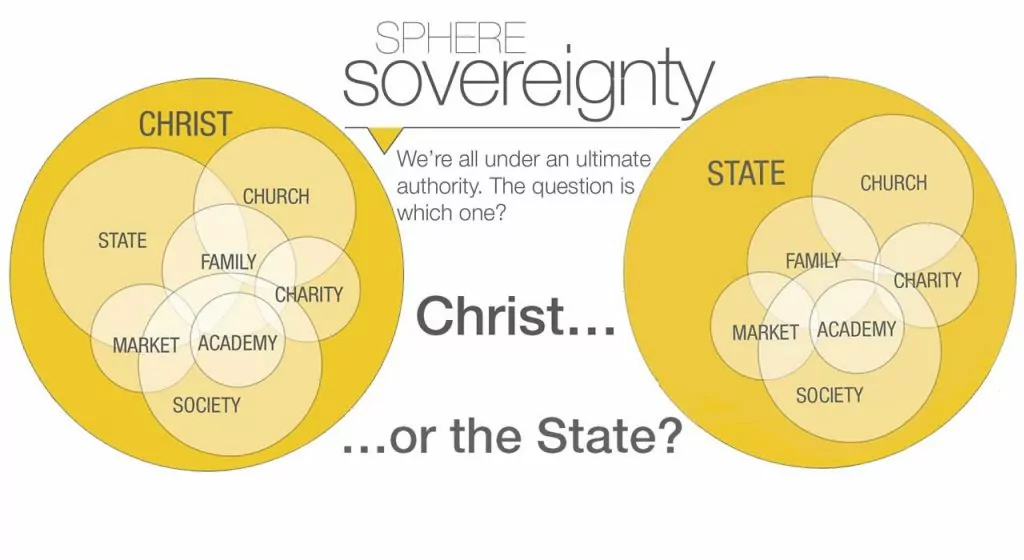

There are whole swaths of theologians and scientists associated with Biologos, the Faraday Institute, and the Canadian Scientific and Christian Affiliation who are trying valiantly to hold together their Christian faith with evolutionary science. And the money of the Templeton Foundation will ensure that pamphlets, presentations, conferences, and books, will bring these views to the Christian public. Holding to Dooyeweerdian philosophy’s sphere sovereignty may help some of these Christians compartmentalize their biology, geology, and their faith, but that philosophical school has been subject to severe criticism in our tradition, and on precisely this point.(14) I fear that the dissonance of EBP itself with the historic, creedal Christian faith will prove to make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for Christians to keep their faith and EBP together. I also doubt that one can very easily maintain evolution as EBP only.

Q3: IF BIOLOGICAL EVOLUTION IS TRUE, WHENCE SIN AND SUFFERING?

One question remains. Keller words this “layperson” question as follows, “If biological evolution is true and there was no historical Adam and Eve how can we know where sin and suffering came from?” He responds in short,

Belief in evolution can be compatible with a belief in an historical fall and a literal Adam and Eve. There are many unanswered questions around this issue and so Christians who believe God used evolution must be open to one another’s views.

Keller finds the “concerns of this question much more well-grounded” than the first two questions. With reference to the first two, he summarizes, “I don’t believe you have to take Genesis 1 as a literal account, and I don’t think that to believe human life came about through EBP you necessarily must support evolution as the GTE.” But as regards this third question he wants to maintain that Adam and Eve were historical figures and not mere symbols. In this regard he differs from those who are more liberal with the text of Genesis 1–3.

In part agreeing with Keller

As with the last question Keller entertained, I again find him making some strong and valid points but ultimately proposing solutions that don’t work. He is concerned that if the church abandons belief in a historical fall into sin, this might “weaken some of our historical, doctrinal commitments at certain crucial points.” Two such points are the trustworthiness of Scripture and the scriptural teachings on sin and salvation.

He correctly asserts that, “the key for interpretation is the Bible itself.” He adds that he doesn’t think Genesis 1 should be taken literally because he thinks the author himself didn’t intend this. However, we have earlier weighed his case and found it wanting. His principles sound good, but he doesn’t practice them. Moreover, he fails to talk about the ultimate author of Scripture, the Holy Spirit.

When Keller favourably quotes Kenneth Kitchen to the effect that the ancients did not tend to historicize myth, that is, think that their myths really were history, but rather tended to turn their history into myths, celebrating actual persons and events “in mythological terms,” we can again agree. This supports the view that the original message is the truth we find in Genesis, and that the myths of the surrounding nations adulterated this.(15)

The Derek Kidner model

In 1967 Derek Kidner, a British Old Testament scholar ordained in the Anglican Church, published a commentary on Genesis in which he surmised that the creature into which God breathed life (Gen 2:7) could have belonged to an existing species whose “bodily and cultural remains” (fossils, bones, cave drawings, I presume) show that they were quite intelligent but were not up to the level of an Adam. Keller concludes, “So in this model there was a place in the evolution of human beings when God took one out of the population of tool-makers and endowed him with the ‘image of God.’”

However, a problem arises regarding all the other tool-makers. They would have been biologically related to Adam but not spiritually related. Kidner then proposed a second step: “God may have now conferred his image on Adam’s collaterals, to bring them into the same realm of being.” Then, if Adam is taken as the representative of all, they might all be considered by God to be included in the fall even though they are not physically descended from Adam and Eve (this sort of move, by the way, has been welcomed by certain Reformed theologians who emphasize Adam’s federal or covenantal headship, though historically Reformed theologians never separated this from his physical headship).

“Let us make man in our image”

What is lacking in Kidner’s account and Keller’s consideration is more attention to the language of Genesis. God did not simply appoint an existing being to be endowed with his image. Rather God conferred within himself and specifically uttered his determination, “Let us make man in our image, in our likeness, and let them rule . . .” (Gen 1:26). Then verse 27 three times uses the word “created,” when it says, “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” Thus, God spoke of “making” and “creating” man in chapter 1, while in chapter 2 the manner of this creating was specified in that God “formed the man of dust from the ground” and “fashioned/constructed a woman from the rib he had taken out of the man” (2:7, 22). Speaking of a mere endowment or bestowal of God’s “image” on an existing hominid, Neanderthal, or whatever it was, doesn’t do justice to such terms as “created,” “made,” “formed,” and “fashioned.”

Suffering and death before the fall?

Moving on to the problem of death before the fall, Keller acknowledges that this is a very prominent question. He doesn’t propose a fulsome answer, but offers a number of points by which his Biologos fellows could help Christians overcome these concerns. He does this by highlighting aspects of the creation which, in his view, show that “there was not perfect order and peace in creation from the first moment” (italics added).

These aspects include the initial chaos which God had to “subdue” in the successive days of creating, the presence of Satan, the fact that the world was not yet “in a glorified, perfect state” and the view that surely there had to have been some kind of death and decay, else the fruit on the trees would not even have been digestible. What response can we give to this?

First, we must emphasize what the Scriptures emphasize, “And God saw all that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31), the climax of all the other affirmations of the goodness of creation in that chapter (Gen 1:4,9,12,18,21,25).

Second, we can agree that good bacteria were present, to digest food, for God gave all the plants for food (Gen 1:30; cf. Gen 9:3) and even in the new creation the tree of life will bear fruit every month and its leaves will be used for healing (Rev 22:2). Although Revelation describes this symbolically, the idea of plant death in some sense is not averse to the new creation (cf. Isa 65:25). Thus digestion and plant death before the fall are something good, not something evil.

Third, God did not have to subdue the chaos as though it were an active power against him. Rather, he took six days to form and shape what he had initially produced on the first day so that he would set the pattern of our lives and manifest himself as a God of power, wisdom, order, and love.

Finally, the presence of Satan did not make God’s creating work as such incomplete or evil. Rather, Satan had chosen to rebel, had destroyed the peace of heaven, but had not yet instigated our human rebellion. So none of Keller’s points stand and certainly none of them provide any scriptural evidence whatsoever of suffering and death before the fall. We must shun any suggestion that God is the one responsible for sin, evil, and suffering, or that suffering and evil are just natural developments and not a result of our sin.

Spiritual death, not physical?

One final attempt by Keller to find some room for suffering and death before the fall emerges from the distinction between physical and spiritual death. If one treats the threat of death in Genesis 2:17 and the curse of death after the fall as simply indicating spiritual death, then all of the hundreds of thousands of years of animal death before Adam and Eve are no problem. As Keller writes, “The result of the Fall, however, was ‘spiritual death’, something that no being in the world had known, because no one had ever been in the image of God.” Note that this is simply a consistent application of the idea that God “bestowed” his image on at least two hominids (or whatever they were) and thereby “elected” them to be humans. Before this all creatures were only animals.

However, this separation of physical and spiritual death is artificial. The refrain of Genesis 5, “and he died,” underlines how the curse on creation was effected in a very physical way. We realize that Adam and Eve did not drop dead physically, the moment they disobeyed. But at that very moment they put themselves on the path of death, rebelling against God, and running from the Author of life. Only in the promise of the Seed could they still find hope – both physical and spiritual.

Conclusion

I don’t think Kidner’s model or Keller’s attempts to provide rhetorical suggestions to his fellow Biologos members have any scriptural weight behind them. These are attempts to accommodate theories that simply do not fit the message of Scripture. Nor do I agree with Keller that the right attitude for the church is to have a “bigger tent” in which we can peacefully discuss together the ways in which we as Reformed Christians might accommodate to Scripture the view that humans descended from other species by evolutionary biological processes. I am convinced that such views are serious errors that need to be kept out of the church of Christ. They disturb the peace. Defending the church against them preserves the peace within.

While I appreciate many of Keller’s writings on apologetics and church planting and have expressed my appreciation in particular for the way in which he pointed out the absurdities of holding to evolution as the “explanation of everything,” I hope that this review essay will help Reformed and Presbyterian churches maintain adherence to their confessional statements.

God created all things good in the space of six days. He made us – from the moment of our existence – as his vice-gerents, representing him to creation and responsible to him. We pledged allegiance to his enemy when we yielded to Satan’s suggestion. Thus we are responsible for sin and death; it is our fault, not God’s. But thanks be to God that his work of grace in Jesus Christ has opened the way for forgiveness, new life, and ultimately, a new creation.

Footnotes

1) Keller’s paper can be found online at http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Keller_white_paper.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar. 2016.

2) See http://reformedacademic.blogspot.ca/2010/03/tim-keller-on-evolution-and-bible.html. Accessed 27 Feb 2016.

3) For this debate see https://adaughterofthereformation.wordpress.com/2012/04/04/is-dr-tim-keller-a-progressive-creationist/. Accessed 27 Feb 2016.

4) In addition, Keller’s note 17 on page 14, linked to a different section of his paper, asserts that prose can use figurative speech and poetry can use literal speech. It appears, then, that he undercuts his own argument.

5) See my blog entry at http://creationwithoutcompromise.com/2016/02/03/the-lost-world/.

6) See, for instance, http://reformedacademic.blogspot.ca/2010/03/response-to-clarion-s-ten-reasons.html. Accessed 24 Feb 2016.

7) See http://veritas.org/talks/clip-explain-away-religion-tim-keller-argues-we-cant/?ccm_paging_p=6. Accessed 24 Feb, 2016.

8) As an example of an evolutionary creationist attempting to defend the evolutionary link from egg-laying reproduction to placenta-supported reproduction, see Dennis Venema’s recent essays on vitellogenin and common ancestry at Biologos. See http://biologos.org/blogs/dennis-venema-letters-to-the-duchess/vitellogenin-and-common-ancestry-does-biologos-have-egg-on-its-face. Accessed 25 Feb 2016.

9) See my essay entitled, “In Between and Intermediate: My Soul in Heaven’s Glory,” in As You See the Day Approaching: Reformed Perspectives on the Last Things, ed. Theodore G. Van Raalte (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2016), 70–111.

10) See https://sixteenseasons.wordpress.com/2014/12/04/evolution-and-the-gallery-of-glory/. Accessed 27 Feb 2017.

11) See https://yinkahdinay.wordpress.com/2012/12/25/howard-van-tills-lightbulb-moment/. Accessed 26 Feb 2016.

12) See his book, The Evolution of Adam (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press 2012), ix–xx, 26–34.

13) See https://yinkahdinay.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/walhout-gets-it/. Accessed 26 Feb 2016.

14) For example, see J. Douma, Another Look at Dooyeweerd(Winnipeg: Premier Printing, 1981).

15) See remarks from E. J. Young in the discussion of the genre of Genesis 1.

Dr. Ted Van Raalte is the professor of Ecclesiology at the Canadian Reformed Seminary in Hamilton. This article first appeared in the April 2016 issue under the title "Countering a Reformed conservative’s case for evolution: Examining Tim Keller’s white paper 'Creation, Evolution, and Christian Laypeople'" and a slightly different version of this article can be found at CreationWithoutCompromise.com. ...