Curiosity can be downright lethal… and not only to cats. In our Internet age, curiosity can quickly take us where we must not go.

But curiosity can also be a force for good. This investigative itch can drive us to discover more about God, digging deep into His Word, or heading out into His creation, magnifying glass in hand, to see all there is to see.

In Curious: the Desire to Know and Why your Future Depends on It Ian Leslie makes a useful division between two main sorts of curiosity – epistemic and diversive. There isn’t simply “good” versus “bad” curiosity but more a matter of “focused” versus “unfocused,” though as you might guess, the focussed sort is generally the more helpful sort.

Diversive curiosity

“Diversive curiosity” is, as Leslie puts it, an “attraction to everything novel” and it “manifests itself as a restless desire for the new and the next.” Leslie explains:

The modern world seems designed to stimulate our diversive curiosity. Every tweet, headline, ad, blog post, and app at once promises and denies a satisfaction for which we are ever more impatient.

This quest for the “new and next” isn’t necessarily bad – this is why new questions get asked, new interests are discovered, and new people are met. But Leslie argues that while “unfettered curiosity is wonderful; unchanneled curiosity is not.”

What problem is there with unchanneled curiosity?

It doesn’t fix itself on anything. It lacks purpose or discipline – diversive curiosity might start off well-intentioned, but if it has nothing to focus on then a search for “Calvin’s thoughts on art” can quickly turn into hours spent on “The art of Calvin and Hobbes.”

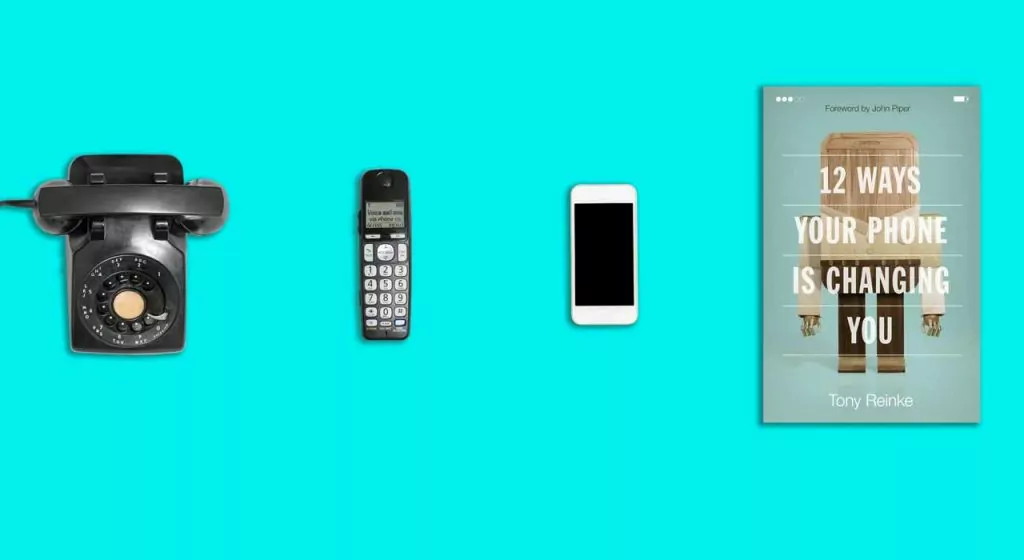

Leslie recounts a question that was posted to Reddit: “If someone from the 1950s suddenly appeared today, what would be the most difficult thing to explain to them about today?” The favorite answer was: “I possess a device in my pocket that is capable of accessing the entirety of information known to man. I use it to look at pictures of cats and get into arguments with strangers.”

We have access to an inexhaustible source of knowledge, right in our back pocket. Want to study Economics, or read Calvin’s Institutes, or learn how to change the oil on your Toyota sequoia and it’s all just a few key taps away. And when it comes to collaborations, we can call on people in the next town, the next state, or the next continent!

But so long as we let our curiosity run free – flitting from one tweet, one game, one photo, one video to another – then this incredible potential will be unrealized.

Channeled curiosity

Here is where the second sort of curiosity comes in. “Epistemic curiosity” is curiosity with a purpose. Leslie describes this as a “deeper, more disciplined, and effortful type of curiosity.” This sort of curiosity pushes us after reading an intriguing blog post headline to go seek books on the same subject. It’s sustained curiosity. It’s directed curiosity. It’s the sort of curiosity that drives a boy to collect beetles and butterflies, and then when he wants to know more he heads to the library for books. It’s this sort of curiosity that has a girl trying out crayons and pens and pencils and paints to figure out how best she can draw a horse. To get good she’s going to need to sustain this appetite for paper and pen, but more importantly, she’ll need to steer clear of the constant stream of YouTube cat videos and other curiosities that are competing for her attention.

Godly curiosity is fettered

While Ian Leslie values unfettered curiosity, God expects our curiosity to be not only channeled but fettered too.

There is every reason for Christians to be curious – God is infinite, and He’s given us a near-infinite universe to explore. But there are corners of it that we should not investigate. Article 13 of the Belgic Confession warns that we should not:

…inquire with undue curiosity into what God does that surpasses human understanding and is beyond our ability to comprehend.

Some of what God has done is too great for us to understand (election, for example) and when it comes to those matters we need to actively constrain our curiosity. We need to put on some fetters.

There are also more earthy matters that we need to not investigate. We need to fetter our curiosity when it comes to:

- gossip – whether about people we know, or celebrities we don’t

- our rich neighbor’s income

- sexuality – within marriage epistemic curiosity about sex can be a very good thing, but outside of, or before marriage, it can only cause trouble

In other words, we shouldn’t be curious about matters beyond us, or matters that should be beneath us.

Freeing us from distractions

When it comes to diversive curiosity – the attraction to the new and next – there are no biblical texts telling us how many cat videos in a row are too many in a row. God hasn’t told us how many times we can check our Facebook newsfeed in an hour, or what time of night we need to turn off our phone. There are no stated limits as to how many tweets we can read, how many Instagram pictures we can view, how many blog posts we can click on, each day. So how can we know how much is too much?

The Westminster Shorter Catechism gives us a clue when it explains that Man’s purpose here on earth is “to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.”

How does that help?

Well, if we’re too busy to pray, too busy to read the Bible, too busy to be a part of the communion of saints, too busy to act as God’s hands and feet here on earth, too busy with all sorts of distractions to glorify God, and too busy enjoying these distractions to enjoy God, then wherever the line might be, we can be sure we’re way over it!

So how can we free ourselves from these distractions? Part of it will involve putting down the smartphone, tucking away the tablet, and turning off the computer. We could consider:

- Putting tight limits on family members’ screen time each week, with more severe constraints for the very young (many doctors suggest children under 2 shouldn’t watch TV at all) and for out-of-control kids.

- Shutting down the Internet for the evening (which still allows kids to use their devices to read) or the afternoon, or only having it on for weekends or for homework.

- Going on a month-long technology fast to allow your family to get proper priorities back in place – this is an option that most children will hate (and many an adult) but the more passionate the resistance, the stronger the case for this intervention.

While these practical suggestions will be helpful they also aren’t enough. We need to address this as the sin problem that it is. When we can’t control our curiosity, when it controls us, we’re enslaved. When our curiosity doesn’t direct us to God, but distracts us from Him, we’re committing idolatry, making YouTube videos and Instagram pics our first priority.

Instead, we can seek ways to direct our curiosity in a God-honoring fashion. Our God is infinite, so there’s no shortage of wonders to explore, whether that’s God Himself, His Word, His world, the bodies He gave us, the family He placed us in, the talents He chose for us, the friends He provided, or the communion of saints He surrounded us with. There’s no shortage of wonders to wonder about. May God help us control our curiosity, so that in this too all we do can honor Him.