Human Rights

The foundation of Human Rights? God's prohibitions

Human rights.

A noble phrase, to be sure. But in a godless world, there are no rights, because a human right, to be a right, must demonstrate an authority greater than the authority of the state. This is why in a fascist state there are no rights, because there is no authority recognized as being superior to the state. Where there are only the edicts of the state, there are no rights, only privileges and crimes: privileges the state grants (and can take away) and crimes it forbids.

Rights, privileges and crimes all have similar natures. They all spring from prohibitions. Take the edict “you shall not commit the crime of murder.” The crime is defined by a prohibition on human behavior. Similarly, the right to life springs from the Godly prohibition on human behavior found in the commandment “thou shall not murder.”

This is the common nature between crimes, privileges, and rights. However, when the state respects no authority greater than the state (fascism), rights become nothing more than privileges that are granted by the state. Only when the state recognizes Divine Authority is there an opportunity for human rights.

On crimes:

The state typically defines crimes in two general categories: mala in se, and mala prohibita. Mala in se are crimes that are inherently evil, like murder. Mala prohibita are crimes only because the state says they are, like, for example, going 55 miles/hr in a 40 miles/hr zone.

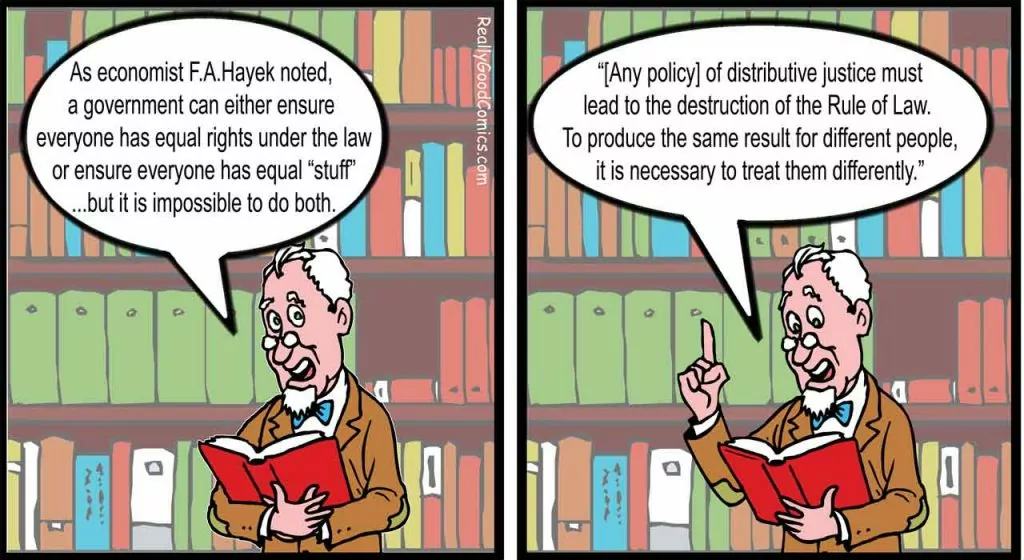

The state which fails to recognize Divine Authority cannot declare crimes mala in se, - inherently evil – because there can be no good and evil without the recognition of a moral order superior to the state. Likewise, a state which fails to recognize Divine Authority can make no claim to the “rule of law” rather than the “rule of edict.” The rule of law implies that members of the ruling class can be held accountable to a standard which has greater authority than the state. When the state recognizes no authority superior to the state, there is no law – there is only tyranny.

On privileges:

The state typically grants privileges under two general categories: grants based on the pragmatic effect of the privilege (weighing the degree to which the privilege will do the most good for the greatest amount of people), or grants based on feudal relationships. Feudal societies are present now in most western countries, most Marxist countries, and virtually all dictatorships. Under feudalism, your rights are based upon who you know, not on equal status under the rule of law.

However, for some unknown reason, the people behind the granting of privileges have a need to establish some basis for each grant, and usually, these bases are set forth within their roster of privileges. By setting forth reasons, the granting of privileges doesn’t appear to be what it actually is: the exercise of naked force.

For instance, the Preamble of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares the foundations for the “rights” proclaimed therein as:

- the declaration of the international family of governments (we say it is so)

- the proclamation of the common people (the common people say it is so, at least so much of their opinion that we were actually willing to listen to)

- the necessity to create the rule of law in order to stop rebellion (the pragmatic reason)

- faith in equal human rights and human dignity (patronizing the religious community with a “faith” statement that is otherwise patent nonsense, since there are no human rights or human dignity under secular humanism).

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by a mere majority of the general assembly of the United Nations, with the Soviet bloc and Saudi Arabia abstaining. Because the vote was not unanimous, the declaration is not even “global” let alone “universal.” Furthermore, because it makes no claim to Divine Authority, it is setting out only a roster of privileges. Further still, it is non-binding on all of the member states. Consequently, calling the document a Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a patent lie. In reality, it is merely the Advisory Declaration of a Majority of the UN General Assembly as to preferred government-granted privileges.

The Canadian Human Rights Act is modeled on this Universal Declaration, adopting similar class distinctions. Initially, the Canadian Human Rights Act did not protect people on the basis of their sexual orientation, while the Universal Declaration did. The CHRA was subsequently amended by judicial fiat to encompass this group.

On human rights:

As I have said, the commonality among crimes, privileges, and rights, is that they spring from prohibitions on human interaction. Crimes and privileges are proscribed by the actions of the state, although quite often that state will call the privileges they grant “rights” when in fact, the edict itself is a tort or even a crime (anti-discrimination legislation which claims to set forth a “human right” is in fact a civil wrong when the sanction is a fine, and a crime when the sanction includes incarceration).

Privileges may approach actual rights only when they correctly (that is to say, rightly) identify the right as pronounced within the Godly order (such as the right to worship freely), but when such “rights” are granted by the state – and therefore subject to revocation – they are not rights; rather, they are state-granted privileges.

Consider how far we have strayed from this understanding. In 2006, the governing Socialists in Spain submitted a bill to grant “human rights” to four species of animals. The species were chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans: the so-called “great apes” or “pongids.” The Spanish government sought to attach “human” rights to apes by edict of the state, apparently because they believe that apes are human too.

Human rights spring from prohibitions on human behavior. The right to free speech – a trait indigenous only to humans - for instance, springs from the prohibition on the government to act contrary to free speech.

God-given rights

Now, consider the Godly prohibitions set forth in Exodus 20:

I am the LORD thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shall have no other gods before me.

Thou shall not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shall not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the LORD thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me; And showing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my commandments.

Thou shall not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless that takes his name in vain.

Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days shall thou labor, and do all thy work: But the seventh day is the Sabbath of the LORD thy God: in it thou shall not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor thy maidservant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates: For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day, and hallowed it.

Honor thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the LORD thy God gives thee.

Thou shall not kill.

Thou shall not commit adultery.

Thou shall not steal.

Thou shall not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Thou shall not covet thy neighbor’s house, thou shall not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbor’s.

It is from this roster (although this is not an exclusive list) that our “human rights” spring. Let me stress here that we have no “right” as opposed to the will of God – He is the author of our faith, our salvation and our rights. But from this roster, human rights accrue to us because if God has prohibited it, who is man to overrule?

We therefore have a right to hold our God as superior to all other proposed gods, including the state, the financial system, the school system, the dollar, consumerism, capitalism, Marxism, fascism, communism, socialism, and so forth. God has commanded us to have no God before him; we therefore have a God-given right to be free from the state placing itself above God. From the time of Nebuchadnezzar to the modern world, there is a failure of certain leaders to recognize that it is God who establishes powers and authorities on earth according to His purpose. As Nebuchadnezzar put it:

“I Nebuchadnezzar lifted up mine eyes unto heaven, and mine understanding returned unto me, and I blessed the most High, and I praised and honored him that lives forever, whose dominion is an everlasting dominion, and his kingdom is from generation to generation: And all the inhabitants of the earth are reputed as nothing: and he doeth according to his will in the army of heaven, and among the inhabitants of the earth: and none can stay his hand, or say unto him, What doest thou?” (Daniel 4:34-35).

By means of the prohibition in the Second Commandment, we obtain the human right to reject idol worship. No state has yet to recognize this right, yet Germans had a God-ordained right not to worship the idol of Nazism. Russians had a God-ordained right not to worship the idol of Vladimir Lenin. Americans have a God-ordained right not to worship pagan idols. Canadians have a God-ordained right not to worship secular humanism. All of us in the modern world have a God-ordained right not to worship the religions of mother earth, the sun, the solstice, science or Darwinism. We have a God-ordained right to reject idols.

And so it goes. We have a right to be free from adultery. We have a right to own our property and to be free from theft. How broad is the right to property? The Tenth Commandment declares that we have a right to any thing that is ours. This includes our marriages, our families, our employment relationships, our intellectual property, our real property and our personal property. Thou shall not steal, and thou shall not covet. It is from these prohibitions that we claim God’s ordination of our right to property.

Right to life

But let us take a moment to discuss the right to life. God says, thou shall not kill. The Hebrew term used in this instance is rashach (to intentionally kill a human being) rather than the term shachat (to take the life of an animal or human). This prohibition creates the right to be free from murder – the right to be free from someone intentionally taking your life. This is the source of our God-ordained right to life.

We must obtain the sense of this, because there can be no question that the rising international state is concluding quickly that there are too many people on earth, who are eating too much food, using too much oil and creating too many “greenhouse gases.” Unless the state is reminded that there is an authority to which the state will ultimately answer, their solution, which is almost always death, will soon be upon us, particularly when they conclude that your right to life is merely a state-granted privilege – one that they gave, and one that they can take away.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in the July/August 2008 issue.