Whether they’re happening inside the Church or out in the public square, debates about how far freedom of conscience extends can be confusing. Should Christians be compelled to take a vaccine that’s been tested on the fetal remains of an aborted child? Should Christian business owners have a right to refuse a service that would violate their conscience, like baking a wedding cake for a same-sex ceremony? How do Christians respond to government mandates or policies that they cannot follow in good conscience? And how do we deal with conscientious disagreement within the Church?

The specifics of freedom of conscience can be complex and nuanced and are often misunderstood. Abraham Kuyper called the conscience:

“the shield of the human person, the root of civil liberties, the source of a nation’s happiness.”

Why is it so important? To answer that question, let’s begin by looking at what the conscience is and is not.

What is “conscience”?

Definitions of conscience vary, but they center around the idea of what someone believes to be right and wrong. The conscience is a moral compass that helps direct people’s actions. In that sense, conscience is personal and subjective because it condemns or excuses one’s own conduct, not that of another person – after all, you don’t get a guilty conscience because of someone else’s behavior.

However, conscience is also based on an objective and general standard. The Bible explains that the conscience is given by God to both Christians and non-Christians and it helps people apply their knowledge of right and wrong to their behavior, both past actions and decisions about future actions. The New Testament also speaks of the importance of having a good conscience by following its direction and doing what is right (see Rom. 2:15, 1 Tim. 1:5).

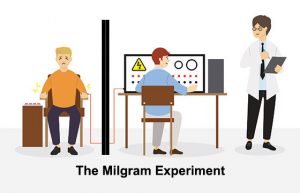

Christian political scientist David Koyzis, in his book We Answer to Another, tells a story about the Milgram Experiment which relates well to conscience. The experiment was a study designed to look at how people respond to authority. The experimenter would select two participants and assign one the role of teacher, while another volunteer would be given the role of student. The person selected as the teacher was instructed to apply an electrical shock of increasing voltage to the other person – the student – who was in a different room. Now, unbeknownst to the teacher, the other person was actually an actor being paid to play the part. Although the teacher could hear the apparent pain experienced by the person in the next room, most individuals would continue applying electric shocks – despite increasing screams and pleas to stop – when instructed to do so by the experimenter. However, two participants were unwilling to keep going along with the instructions. Both were Christians. They followed the experiment instructor’s commands for a time but stopped sooner than most other participants, knowing that they were responsible for their actions and stating that they were answerable to a higher authority.

Christian political scientist David Koyzis, in his book We Answer to Another, tells a story about the Milgram Experiment which relates well to conscience. The experiment was a study designed to look at how people respond to authority. The experimenter would select two participants and assign one the role of teacher, while another volunteer would be given the role of student. The person selected as the teacher was instructed to apply an electrical shock of increasing voltage to the other person – the student – who was in a different room. Now, unbeknownst to the teacher, the other person was actually an actor being paid to play the part. Although the teacher could hear the apparent pain experienced by the person in the next room, most individuals would continue applying electric shocks – despite increasing screams and pleas to stop – when instructed to do so by the experimenter. However, two participants were unwilling to keep going along with the instructions. Both were Christians. They followed the experiment instructor’s commands for a time but stopped sooner than most other participants, knowing that they were responsible for their actions and stating that they were answerable to a higher authority.

When asked to do something wrong, we too are responsible for our actions and answerable to a higher authority.

Ultimately, the foundation for freedom of conscience is found in the sovereignty of God. Every human being has various authorities in their lives, such as parents, employers, church leadership, or civil government. Each of these has legitimate authority over us, but that authority is also limited. The only One who is sovereign over the conscience is God, and if another authority commands us to do what we believe is sin – what we believe violates how God wants us to act – then we can appeal to freedom of conscience. The conscience is a shield that protects against the abuse of authority and points instead to the one Higher Authority.

Conscience and the public square

Debates around conscience are becoming increasingly relevant in our society and are most noticeable within certain vocations. Can medical professionals refuse to help a patient access abortion, assisted suicide, or sex-change surgery? Can marriage officiants refuse to marry a same-sex couple? Can a photographer decline a request to take photos at a same-sex ceremony? Can a publisher decline to print pro-abortion pamphlets?

Increasingly, our society answers “no.” To allow people to conscientiously object is seen as simply discriminatory and bigoted. Our society needs to understand that a conscientious objection in these cases is not a rejection of an individual person, but a refusal to commit what the objector believes to be a sin or to participate in sinful activity.

Today it’s often Christians who are being pressured to violate their conscience. However, there are others who seek the same protections for their conscience. It’s this freedom that an atheist doctor appeals to when he determines he cannot participate in euthanasia, based on his oath to do no harm. And what of the fashion designers, back in 2016, who had principled objections to designing an inauguration dress for First Lady Melania Trump? When these designers announced they would not make the dress because they didn’t want to be associated with newly elected President Donald Trump’s administration, many celebrated their decision as taking a principled stand. Likewise, some in our society want abortion-supporting publishers to be allowed to decline print orders for pro-life material, or for a gay business owner to be allowed to refuse to rent a hall for an event that promotes biblical marriage.

Yet increasingly, the same people want to see Christians reprimanded for acting according to their beliefs.

For Christians, the answer to the questions above might be easy. But we have our own disputes about conscience within the Church as well, such as what kind of entertainment is permissible or what it looks like to honor the Sabbath Day outside of corporate worship.

When conscience pricks

Of note, the strongest commands of conscience are often negative, in terms of what you are not permitted to do, rather than what you may or must do. For example, if you use foul language, your conscience will likely bother you more than if you fail to correct someone else using such language. Or, if a publisher prints pro-abortion pamphlets that he objects to, his conscience will make him feel guilty more than if he fails to promote life as he believes he ought.

When the conscience commands a person not to do something, the command is about a very specific action. Alternatively, if the command is instead to act on something good, there are often various ways of pursuing that good.

Conscience and the Church

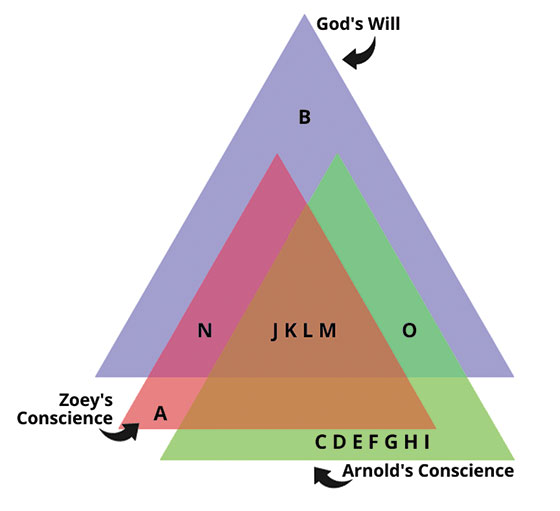

Because of sin, no person’s conscience is perfectly aligned with what God commands in His Word. The chart below is based on one from a helpful book titled Conscience: What It Is, How To Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ, by Andrew Naselli and J.D. Crowley. The authors used it to explain the difference between two people’s consciences, and how they compare to God’s will. The letters within the chart refer to different rules or principles of right and wrong.

Both Arnold and Zoey have added rules to their conscience that are not commanded in Scripture. For example, perhaps Arnold has a history of alcohol abuse in his family, so he adds letter ‘C’ which commands him not to drink alcohol to avoid temptation. Maybe letters ‘D’ and ‘E’ are Arnold’s belief that he must not play cards or any games involving dice. Arnold and Zoey have also both failed to include letter ‘B’ in their conscience. Perhaps this is a failure to consistently honor the Sabbath Day, and their consciences no longer accuse them for it. However, Arnold and Zoey’s consciences are both aligned with God’s will in letters ‘J’ through ‘M,’ where they have rightly applied biblical principles and commands to their lives and consciences. The natural tendency is to think that if another person has more rules than us, they are legalistic. Alternatively, if they have fewer rules, they are failing to live as Christians. However, Scripture remains the standard to which we must seek to align our conscience.

The conscience can easily become oversensitive by including rules that are not matters of right and wrong. We see examples of the Pharisees in the New Testament who created additional rules for the Sabbath and wanted everyone to abide by them. We might feel unnecessarily guilty if we do not abide by similar rules on the Sabbath.

Alternatively, conscience can become desensitized. Perhaps you use or tolerate foul language that would have shocked you a decade ago, or you consume entertainment that you would have been ashamed of years earlier. Our conscience does not always accurately tell us what is sin and what is not. While it might not always make sense to follow conscience in relation to other authorities, we have a duty to obey it because we cannot commit what we believe is sin.

At the same time, we should be careful when dealing with the consciences of other people. In 1 Corinthians 8, the Apostle Paul talks about whether believers can eat meat offered to idols and refers to consideration for brothers and sisters with a weaker conscience. So, if we believe a brother or sister has a weaker conscience, we must not be a stumbling block to them and cause them to disobey their conscience. On disputable issues, we may realize that someone has a weaker conscience, and we can discuss the biblical principles that apply. Or perhaps they have a stronger conscience, and they can help us understand where our conscience is not aligned to Scripture.

Again, conscience is not meant to be some wishy-washy idea where everyone can believe what they want, like in the time of the judges of Israel, when “everyone did what was right in his own eyes.” There are direct, objective commands and principles that can be taken from Scripture. There are many issues which should not be disputable for Christians and are clear in the Bible.

However, there are also issues where serious Christians can come to different conclusions about what God commands. For example, what activities are not permitted on the Sabbath? Or perhaps more current, how do we navigate government restrictions and the call to honor our authorities versus our callings to obey what God demands of us? What about masking, vaccines, etc., both within the public square and the Church? Christian conscience differs on these issues, and believers can have biblical arguments for why they think God commands or prohibits different actions.

What isn’t conscience?

Some of us might react to the idea that conscience is a kind of subjective belief that is not accountable to other people. We can’t simply say, “well, what’s right for you isn’t necessarily right for me.” Conscience is not merely a personal preference like your favorite food or music. It is also not license to do whatever you please and ignore other authorities. Rather, freedom of conscience refers to moral beliefs that respect a limited sphere of individual authority while still recognizing other legitimate authorities that can impose obligations on us.

As such, the conscience is not unlimited. Some people might abuse the ability to claim conscientious objection out of self-interest or to simply justify their actions. Authorities such as the civil government, church government, employers, or parents do have power to compel or deny certain actions.

However, if the civil government (or other authorities) limits conscience, they must provide good justification for doing so and seek to accommodate conscientious objectors as much as they are able, such as through exemptions for freedom of conscience. Abraham Kuyper again shows the importance of conscience, stating that:

“Ten times better is a state in which a few eccentrics can make themselves a laughingstock for a time by abusing freedom of conscience, than a state in which these eccentricities are prevented by violating conscience itself.”

Conclusion

Ultimately, conscience belongs to an individual and is accountable to God. However, it should also be rooted in Biblical commands and principles. Increasingly, we encounter disagreements in the Church about various issues, while in the public square some Christians’ jobs are threatened because the State fails to recognize conscience. On many matters, Christians will refuse to do something they believe is evil even if others do not believe the action is wrong. The Church has an opportunity to continue to show our society what it means to live according to moral standards based on the will and Sovereignty of God. Wherever we find ourselves, let’s seek to say, “I myself always strive to have a conscience without offense toward God and men” (Acts 24:16).

Daniel Zekveld is a policy analyst with ARPA Canada and the principal drafter of ARPA’s latest policy report on Conscience in Healthcare.