“If God spare my life, ere many years pass, I will cause the boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scripture than thou dost.” – William Tyndale

*****

CHAPTER 1

The Severn burbled alongside its banks. Longer than the Thames, and famous for its tidal bore, the river’s source lay in the moorlands of mid-Wales and its murky depths flowed past the city of Gloucester in three separate channels. There was the western channel; the easternmost channel, also known as the Little Severn; and the formidable middle channel, the one carrying the greatest volume of water, known as the Great Severn. The middle channel was spanned by Westgate Bridge, the longest bridge in England and one much prized by all Gloucester citizens, for it brought much business to the area. It was the route over which much merchandise passed – merchandise such as wood, salt, cloth, corn, wine, and cattle. It was also one of the pathways over which new thoughts and ideas crept into the city.

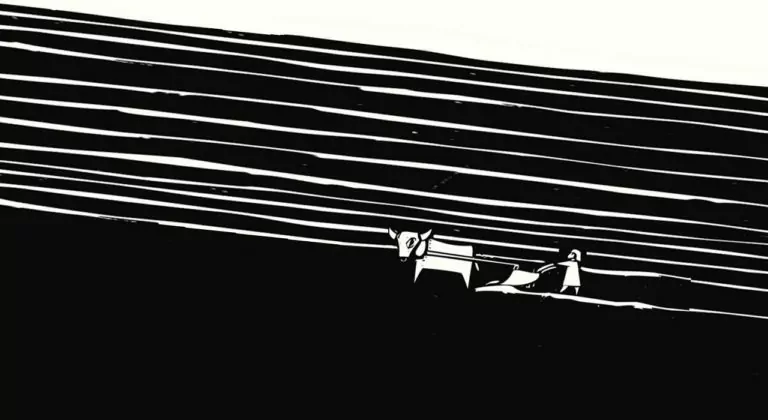

It was 1537. Thomas Drourie, a cattleman, reflected on these matters one early October morning as he guided his herd of cows along the crossover. Dark currents swirled below him. Drourie was a tall man, and for that reason was considered prosperous. The height of most men in Gloucester averaged five and a half feet. Thomas’ over six-foot stature was imposing. Yet when he smiled, the measure of his towering frame radiated friendliness. Dark of hair and swarthy of face, he was a lean, strong fellow, one who embodied hard work and resilience.

The hoofbeats of the cows echoed hollowly on the thick wooden slats. Trekking between his cattle, Thomas bellowed out a noisy, tuneless ditty. He’d noted his animals enjoyed music, for when he hummed or sang during milking the full udders spouted a greater amount of milk into his pails.

The bridge groaned and creaked with the collective weight of the party. Storms and flooding often wreaked damage on its timber anatomy. Almost a citizen itself, the Westgate was considered so dear to Gloucester that often folks would leave a bequest for its upkeep and repair.

“Thomas!”

Startled, he stopped his singing. Turning sideways, he peered down into the face of a Franciscan priest who had managed to edge in next to him between the cattle. The man flanked Thomas, although his plump form in its loose-flapping, wide-sleeved, cassock barely reached the height of the farmer’s shoulders. This man, Thomas thought to himself as he always did when he saw the cleric, was afflicted with bellycheer, afflicted with gluttony. “I haven’t seen you at Mass for a while, Thomas.” The words were calmly but loudly spoken, as need be, for the commotion of the cattle made soft talk impossible.

Thomas gave no answer but calmly continued walking, steering his animals towards the Northgate Street. He knew that Father Serly, for this was the name of the priest, would turn towards Westgate Street, where St. Nicholas’ Church stood at its far end and where he and a number of other friars resided.

“Thomas!” Father Serly’s voice was more intense now and no longer neutral.

“It’s been busy.” It was the only answer Thomas voiced before turning onto Northgate.

There were four main roads leading in and out of Gloucester, all meeting at a main intersection where the town’s high cross stood. All were named from the gates by which they entered town. Thus there were the Eastgate, Northgate, Southgate and Westgate streets. Northgate led to London; Southgate to Bristol; Eastgate to Oxford; and Westgate to Wales. People walked, rode in carts, and journeyed by horse on these unpaved roads. Some four thousand citizens made their home in Gloucester.

Passing the town hall, Thomas longingly eyed the nearby New Inn. Its strong, massive external galleries and courtyards attracted pilgrims and visitors alike. How he yearned to go into the public house and drink some of its frothing ale for he was thirsty after his long morning walk. But with these newly bought cows as his companions, he was forced to amble past the gabled and timbered structure, well aware that the priest probably still stood at the crossroad, eyeing his retreating form suspiciously.

The truth was that Thomas held no high opinion of the local priests, or of any priests for that matter, and only occasionally attended Mass. A devoted cattleman, he spent much time on his farm, waxing poetic to anyone who would listen about the state of his cows, calves, and steers. Praising their rich, dark brown color, he often remarked with a twinkle in his eyes that the color resembled the tint of Dory’s hair. And wasn’t she a beauty? Dory was his wife. The bulls in his herd, on the other hand, hued a blue-black shade, and while showing them off he would point to his own hair and grin. All of the Drourie cattle sported white bellies and were finch-backed. That is to say, they all had a white finching stripe along their spine, a stripe which continued on over the tail. Well-developed horns with black tips crowned their heads. Thomas Drourie was inordinately proud of his livestock. Noted for providing strong and docile draught oxen, the beasts also proved to be tender beef when roasted on the spit. As well, they were valued for the richness of their milk. The fat in that milk made a full, hard cheese – cheese with a buttery, mellow, nutty taste. Thomas sold it at the Gloucester market on Westgate Street. Aged for four months, double Gloucester cheese was popular throughout the region.

*****

Lizzie Drourie was born later that same day. Arriving home, Thomas learned that Janey, the midwife, had been closeted in the bedroom with Dory all night. A tinge of fear shivered through his stomach. By his calculations, it was a trifle early for the child to be born.

“We had to send for her about an hour after you left yesterday to pick up the cows at Noent, master. But it’s over now,” Nelly, the kitchen maid, assured him. “Janey just came down before you came home to say all’s well and that you were free to come up.”

Indeed, it was all well, and he relaxed moments later at the bedside of his Dory, his long legs sprawled out under the great bed. She looked weary, mounds of her dark brown hair spread across the pillow. But though her face was exhausted, it was also contented and he was lost in admiration of her.

“It’s a girl, Thomas,” she whispered, “a bonny girl, and I’d like to name her Elizabeth.”

He was of a mind to let her have whatever she wanted and nodded in agreement. “Lizzie, then,” he answered softly.

Janey tutted as she bustled about, carrying the swaddled newborn. A moment later, Thomas curiously peered into the tightly bound bundle she laid into his arms and he suddenly recalled with some alarm that it had been this very day a year ago that William Tyndale had been burned at the stake. He said as much even as he was overcome by the dark eyes of his firstborn daughter. But the memory of Tyndale somehow clouded the joy. “It’s a bad omen for the child,” he added after contemplating Lizzie.

“Oh, tush,” responded Janey, who had little ken of such as Tyndale, “the child is beautiful, your wife is doing well, and you’re just a bit daft not to note it.”

Dory smiled, and Thomas grudgingly had to admit that all seemed exceptionally propitious with both mother and child. So after sitting a while, stroking his wife’s hand and intermittently peering into the cradle where Lizzie had been laid, he left the birthing room for the stable where there was ample room to stretch his legs. And as the door shut behind him, Janey commented disdainfully that recalling the death of someone they had not even known, was ridiculous.

“But,” Dory protested weakly, her mind mostly on the fact that she had just born her first child, “Master Tyndale was, after all, a Gloucester man, Janey. He was from our area. It seems clear to me that all he wanted to do was give the English people the Bible to read. And although I have not read it for myself, I cannot help but think that such a gift had no evil intent. They say that Queen Anne,” she added a moment later, “the poor lass who was executed last year, had a small Bible, a richly ornamented one, and that she wrote the words ‘Anna Regina Angliae’ around its edges.”

It was a long sentence, a bit of a ramble, and she yawned towards the end.

“We’ve no need to read the Bible, lass,” the midwife cheerfully responded, “Why we’ve got the pope, haven’t we, to tell us what we need to know?”

“Yes, but,” Dory rejoined, her thoughts becoming fuzzier, “now that King Henry has made himself the head of the church, we haven’t got the pope anymore, have we? Besides that, I once saw master Tyndale here in Gloucester. He was giving alms to a beggar, and seemed to me to be a most kind and gentle man.”

After these words, totally drained of her physical energy, she fell asleep. For a brief minute, before she continued her cleaning up, Janey stood at the foot of the bed, smiling tender-heartedly at the sight of the spent, young woman. Then she continued her tasks, muttering softly to herself that King Henry was not really interested in being the head of the Church and surely everyone in England knew it. Was it not obvious that the man was only interested in power? And that which mostly occupied his waking days was passing that power on to a male heir. His third wife, Queen Jane, was about to give birth shortly and hadn’t English people like herself been instructed to pray for the child to be a son? Wouldn’t it be something to be the midwife in Hampton Court palace this month? Oh, well, Janey philosophized, even as she tucked a woolen coverlet around the newborn Lizzie, it really wasn’t any of her concern. Then she smiled into Lizzie’s wide-open, dark eyes.

“I stand to benefit from your birth, little one,” she whispered to the baby, “and isn’t that the truth of it! I’ll be needed for a goodly while as your mother regains her strength, and the extra income is most welcome to me. I’ve six moppets at home and their appetite is as large as your father is tall.”

Lizzie blinked and Janey smiled again.

CHAPTER 2

In those days the meadowlands embracing Gloucester were dotted with farms. One of these was the Drourie farm. Comprising two hundred acres, more than half of it was arable, quite suitable for growing crops. Most of the remaining land was meadow with some woodland included. Thomas grew enough produce to feed his cattle. He also bred fine animals, made cheese, and sold what he did not need at market. It was a good way to live, he reflected, as he stroked the finching stripe of one of the cows. Feeling rather emotional because of Lizzie’s birth, he preached softly to the animal. “There is a time to be born,” he murmured, “and a time to die. This is Lizzie’s time to live.”

The cow lowed softly in response and Thomas ground his foot into the hay reflecting that it was perhaps not wise to think beyond what one could know. This daughter, this brand new Lizzie, might live a long, long life, and he fervently hoped that she would, but he should not presume. She might also be followed by more children. Perhaps he would have a son in the years to come, a strong son who would take over the farm when he himself became too old. Lizzie as well, when she grew older, could help around the house and Dory could teach her to become proficient in the cheese making. He smiled to himself, and Albert, the young stable hand, watched his master aimlessly fork some hay into the loft. Albert was only twelve, but a strong, strapping lad.

It was an inheritance that had conferred on Thomas the small but handsome, granite farmhouse. Endowed with demesne, land attached and retained for the owner’s use, the two-storied home had a large kitchen, a bower room, and several side rooms. The projecting porch even boasted a parvise – an enclosed area surrounded by colonnades. The porch also led into a fine hall where the family ate. There were mullioned windows, oak-paneled walls and a sizeable fireplace. The premises suited Thomas and Dory very well, and they employed five servants, all of whom loved and respected them.

The district surrounding Gloucester was not only dotted with farms, it was also dotted with Articles – six articles, to be exact. Written by the king, these specific rules reminded the English who was in charge: not the Pope who lived in Italy, but Henry VIII who lived in England. Still a Catholic at heart, however, Henry’s first article insisted that his subjects continue to holding to transubstantiation – the belief that the bread at Mass was converted into the actual body and blood of Christ. The penalty for not believing this was death by burning at the stake.

Thomas Drourie sometimes pondered transubstantiation as he took care of his cattle. The word was as long as a cow’s tail. Why the king should care that he, Thomas Drourie, should believe this, was a mystery to him. One way or the other, would he not be the same English farmer? Stroking the side of a cow, he grimaced at the thought of church attendance. He liked not the priests that served the Eucharist and avoided going to Mass.

Besides that, there were new ideas coming to the fore in Gloucester, Protestant ideas. Thomas and his fellow citizens were well aware of them. Many deep, and often heated, discussions took place in the New, the Boatman, the Ram, the Bull, the Swan, and other inns in Gloucester. There was open dissension along the English countryside and in the city. Lately a local weaver attending St. Mary de Crypt Church on Southgate Street had denied the doctrine of purgatory because he believed that the Bible did not teach it.

Irritably Thomas slapped the cow’s buttocks and the animal turned its head, fixing its great eyes on her master. Thomas paid no heed. His thoughts wandered on. Although he had no stomach for dissension, he liked neither the church’s nor the king’s ways. Was it not so that the king also had a child named Lizzie, a little maid all of four years old? And did this child not wander around all alone in the royal palace because her mother had been first divorced and then beheaded? Ah, his own small Lizzie, although not a princess, was much more blessed. Did she not have a Dory to care for her?

*****

Lizzie Drourie was an only child for the first five years of her life. Strangely enough, the year after her birth, King Henry issued a royal license that the Bible might openly be sold to and read by all English people without any danger of recrimination. Another royal order was issued as well, appointing a copy of the Bible to be placed in every parish church. It was to be raised up on a desk so that everyone might come and read it.

Overnight Gloucester Abbey became Gloucester Cathedral. Clergy replaced the monks not just in Gloucester, but in all the monasteries and convents throughout England, Wales, and Ireland. Disbanded, their incomes were appropriated for the crown. Any resistance was viewed as treasonable. Under heavy threats almost all of the religious houses joined the new English church, swearing to uphold the King’s divorce and remarriage.

Gloucester Cathedral acquired a Bible also. John Wakeman, the first Bishop of Gloucester, made sure it was placed in an accessible spot and soon citizens cautiously dropped by for a look. Thomas and Dory came as well. Those who were able bought the book from printers, booksellers, or traveling tinkers. If they could not read, and many could not, they persuaded others to read Scripture to them. How different, Thomas and Dory pondered, had been the years before Lizzie’s birth. At that time anyone wishing to read the Bible had to do so secretly.

It was not until just before their second child was born, that Thomas and Dory also purchased a Bible from a traveling tinker. They’d known Philip for a long time, for he was wont to stop by their farm once or twice every year. A versatile man, his cart was filled with all manner of things. Carrying a pocketful of news about current events, he was also well-versed in languages, music, and Scripture.

Thomas, who could read, was much taken with his Bible. Sitting Lizzie upon his knees, in the evenings he read out loud to the child and to Dory. He did not understand all he read, but he felt privileged to be reading. Dory listened attentively from her easy chair by the fire and rubbed her swollen stomach. Another Drourie child grew large within her belly. She wondered if the baby could hear any of the beautiful words that Thomas read. Leaning back, she smiled contentedly. They had never before heard the Bible in their own language.

On the day Dory went into labor, Thomas sent Albert, who was now almost seventeen, for Janey and gave instructions to the dairymaid to take Lizzie to the bower room and keep her occupied, away from her mother. Janey, arriving shortly afterward, first made sure all the doors were unlocked. She explained that it was an old custom and aided childbirth. Thomas was in two minds about this, but Janey insisted. And indeed, it proved to be an easy birth. The boy child, although tiny, appeared healthy. Janey bathed the little, red body before an ash wood fire. Afterward she had him suckle on a cloth dipped in cinder tea, water into which a coal had been dropped. When she saw Thomas staring, she explained good-naturedly that all knew this drove Satan away.

“I don’t recall you doing that when Lizzie was born,” Thomas commented as he watched her, rather uneasy about the matter as it smacked of superstition.

“But you weren’t there all the time, now were you, Master Thomas,” she replied calmly, “and haven’t things been well with that lass?”

Speaking to himself in an undertone, Thomas strode over and lifted the newborn out of Janey’s arms, pulling the cloth out of the baby’s mouth. “Enough now,” he said, “there are other things you can find to do. And one of them is to tell Albert to distribute bread, cheese and ale to the poor of Gloucester. Go on with you and I’ll stay with Dory and the babe.”

His son whimpered in his arms. The face was red and wrinkled, reminding Thomas of his old deceased father. Sitting down by the bed, he studied his wife. She had now born him two children. He was a rich man indeed. Dory was almost asleep but she opened her eyes and smiled at him.

“We’ll name him Thomas for you. But it must be little Thomas, for you are so much bigger.”

And that is how the boy became known throughout Gloucester.

CHAPTER 3

During his first year, Little Thomas drank sporadically and was prone to mewling. Excessive crying caused discoloration around his eyes. Janey concocted a solution of nightshade sap, soaked a clean rag in it and laid it on the baby’s eyes.

“Perhaps he has cramps,” Dory ventured to guess, “I’ve heard that laying babies down flat and pulling their legs straight can help them belch?”

But Janey only smiled at her.

Lizzie proved to be a most helpful and patient sister, child that she herself was. Rocking her brother for hours on end, she often changed his clout, sang to him and kissed him.

“She is a better mother than I am,” Dory confided to Thomas, “and has the patience of a saint. I heard her say the other day ‘Little Thomas, I won’t ever leave you, even if you cry for a year.’”

Thomas smiled. “He will grow out of this crying and this colic, Dory,” he promised, “Just wait and see.”

*****

It was true. By the time Little Thomas turned toddler, he was thriving; and when the child turned six, although still small, he was so full of mischief that the scullery-maid was in fear of him. Intensely curious, he was also a naïve boy. Once, after the cook had wrung the necks of several pigeons in preparation for squab pie, leaving them in the kitchen on the table, she came back to find the boy holding onto one of the dead birds. Blood all over his hands, shirt and breeches, she asked what he thought he was doing.

“I thought perhaps,” he answered with a child’s logic, “that if you wrung the neck the other way, the pigeon might come back to life.”

Then he proceeded to do just that. Shocked, the cook took the bird out of his hands. “Growing chuff-headed, are you? Away with you,” she retorted, “or I’ll put you into the pie as well.”

Little Thomas loved Philip the tinker and often followed him about the farm when he came to call. Because Philip was kind, exemplary of character, and learned, Thomas and Dory did not mind in the least. They hoped the tinker would nurture little Thomas in piety. The truth was that Philip was a highly educated man. Able to read and write, as well as play the viol, Thomas and Dory eventually asked him to become their son’s tutor.

Just prior to Little Thomas’ birth, Henry VIII had founded a school in Gloucester. Previously there had been a school in the Abbey of St. Peter, but because all monasteries had been closed, that school no longer functioned. The headmaster of the new school was a solemn man and one who exacted strict obedience.

But because of his impishness, misdemeanors, and disregard for authority, Little Thomas was not a favorite student. The boy was, in fact, not fitting in very well at all, and was frequently in trouble with the headmaster. This pained Thomas and Dory greatly, for little Thomas was a gifted child. His almost photographic memory enabled him not only to read well but also to quote Latin and Scripture texts at will. The boy’s greatest offence had been climbing the bell tower with some friends, and swinging the clapper loudly during a service, thus bringing shame on himself and his family. He had capped that escapade by putting a duck egg under the cover of the headmaster’s bed and by hanging the man’s pantofles from the branch of a tree a week later. The headmaster did not want to see him back for at least a year, or until, as he had gravely said to Dory and Thomas, such a time as the boy had learned to unquestioningly obey rules and regulations.

Thomas, who had let his son feel the backside of his hand on more than one occasion, was at his wit’s end. Several times neighbors had suggested that little Thomas was heading towards a wicked end and that his parents must see to it that he was disciplined or he would turn into a ne’er-do-well. It was at precisely this time that Dory and Thomas asked Philip if he would stay and tutor the child. After some careful consideration, Philip agreed to do this for a time, thus becoming a permanent resident of the Drourie farm.

*****

Change was blowing through England during the children’s early formative years. In 1547 King Henry VIII died and was carried to his grave in pomp and splendor. Edward VI, Henry’s son, was crowned in his place. Although only nine years old, Edward had been instructed by Protestant teachers and his youthful heart was warmly turned towards the Reformation. He was a child used by God and one of the first things young Edward did was to overturn his father’s Six Articles.

*****

A few years after Edward’s ascent to the throne, little Thomas turned both eleven and more intractable. The boy, who attended church regularly with his father, mother, Lizzie and Philip, heard Dr. Williams preach in one of the churches in Gloucester. Dr. Williams was the city’s chancellor. A recent convert to Protestantism, Williams had publicly chosen the Protestant faith over the Catholic faith.

It is strange how God uses men’s words to change hearts, even very young hearts. And so it was on the day on which Dr. Williams preached, that little Thomas, for so he was still known, was transformed.

“The sacrament,” so Dr. Williams echoed solemnly forth from the fine pulpit as he spoke of the Mass, “is to be received spiritually by faith. It is not to be received carnally as the papists have heretofore taught.”

Now these were difficult words, and yet Little Thomas repeated them verbatim to Philip, his new teacher, as they were out walking together. “What think you, Master Philip,” he asked, “that these words mean?”

The tinker did not respond immediately. But after some thirty or so steps, he finally spoke. “First of all, I think that we must never in our thoughts or words, pity the Lord Jesus for dying on the cross.”

The child looked up at him questioningly. He did not understand. “To pity someone,” the tinker went on, “is to place yourself on a higher level. Our Savior Jesus Christ, is Lord over all and never on a lower level than we are. What think you? That we can make Him bread and kill Him again and again? He died once, child, and that willingly, of His own accord.”

Overhead a lark, nondescript and brown, sang an extravagant melody. “I think,” Philip went on, “that it might help you to call to mind the time that Jesus was eating bread with His disciples in the Upper Room. Do you recall it?”

Little Thomas nodded.

“Picture in your mind then, their gathering around a wooden table, a table such as we eat from together in the great hall. Hear in your heart what Jesus said to them, and says to us now, as He broke the bread: ‘This is My body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of Me.’”

As they were walking, the pair were traipsing through one of the fields adjoining the farm. Philip carried his viol case for the idea was that there was to be a music lesson out in the quiet of a pastureland. There were cattle grazing some distance away.

“Jesus did not mean that He was actually present in the bread, Thomas. What Jesus meant was that whenever people would eat the bread in the future, they were to recollect, to remember, that He offered up His body. This He did on the cross shortly after that supper, little Thomas. And we are to remember this and to believe it.”

Again, a melodious jumble of clear notes and trills rang through the sky overhead. The boy tilted his head up to gaze after the lark. The bird sang as it flew. Little Thomas stared up at the creature. He appeared to be not listening.

“To remember and believe that Christ died for you,” the tinker went on, making his words simpler, even as he stood next to the child, “is to know that you have eternal life. And then you can joyfully sing even as yonder lark.”

As the boy still remained quiet, he went on slowly, probing the heart. “You are getting too old to be known as Little Thomas. I think I will call you Tom from now on. Do you believe what I have just told you, Tom?”

The child nodded and followed up the nodding with a question. “Can we have a music lesson now, Master Philip?”

Now it was so, that Philip was proficient in viol playing and, at Thomas’ and Dory’s request, he was beginning to pass this skill on to their son. A distant relative of the violin, the viol was a bowed instrument with frets. Flat-backed, it was played while set on the ground between a player’s legs. Its tone was quiet but had a distinct, low quality. A gentleman’s instrument, it was played in salons, whereas violins were more often played on streets to accompany dances or to lead in wedding processions. The Drouries hoped the learning of the viol might calm their child and stand him to good advantage.

Philip concurred with Tom’s wish. “Fine, child. Let us sit ourselves down on this log.”

They had come to a small copse. A field lay in front of them and a forest behind them.

Philip took the viol out of its bag, and both seated themselves on an old, fallen horse chestnut tree trunk lying in front of the thicket. It was quiet, except for the lowing of some distant cattle.

“Hold the bow,” Philip instructed his pupil, propping up the instrument between the child’s legs, “betwixt the end of your thumb and the two foremost fingers of your right hand.” Tom eagerly reached for the convex stick. He loved the music Philip often made in the front room as they sat evenings by the fireplace. The viol’s body was light and the six strings seemed to him to be magical.

“Now fasten the thumb and first finger of your left hand on the stalk.” Philip knelt down in front of the boy. His hands instructed the much smaller hands – hands which worked fearfully hard at contorting fingers to meet the requirements. It was difficult and awkward because this was the first lesson. Through his concentration, Tom thought he heard a snorting sound. Looking up over Philip’s shoulder, his hands froze. One of his father’s bulls, massive and terrifying, the black tips of its white horns aimed directly at them, was galloping through the meadow in their direction.

“Master Philip!” he gasped, “Look yonder.”

Philip turned his head and immediately stood up. Taking the viol away from Tom, he commanded the lad to stand behind him and then to quickly walk backwards towards the nearby woodland. He himself sat down on the tree trunk, calmly placing the viol downwards between his legs. Glancing over his shoulder he saw that Thomas was moving, moving slowly and woodenly.

“Obey me immediately,” he ordered again, “Walk faster, Tom, walk faster, child. And find a tree behind which you can stand.”

“What…. what about you?” the boy stuttered, tripping over both his words and his feet.

“I believe the bull is bellowing in a B flat and I shall try to outdo him,” Philip answered and proceeded to draw his bow across the strings.

The low, quiet hum of the viol resonated across the field. It met the bull’s wheezing midair. Though Tom was only some thirty feet away by this time, he stopped walking backwards at the same moment that he saw the bull stop charging. To his great amazement the boy beheld the animal shake its bulky head a few times and then peaceably turn and amble away.

“Well now, you have learned two rather unique and wonderful things, Thomas,” Philip said, when the boy was back at his side. He kept playing as he spoke, sliding the bow over the strings, harmonious notes spilling onto the grass around and beyond like heavy raindrops.

“What?” the boy asked, his heart still thumping as he watched the backside of the massive bovine saunter away.

“Firstly that bulls do not like the key of B flat,” smiled his teacher.

Tom grinned, although tremulously. “And what is the second,” he demanded a moment later.

“That Almighty God keeps an eye on those who call out to Him in trouble.”

“Oh,” replied Tom, “and did you call out?”

“Yes,” accorded his teacher.

The boy stared off into the field. The bull was still in retreat and seemed to not even remember their existence. He sighed heavily and then grinned again, high spirits returning.

“I am sorry for one thing,” he joked, “and that is that Lizzie was not here to see it, for she will never believe me when I tell her what happened.

CHAPTER 4

That very evening Tom fell ill of a high fever. It charged at him even as the bull had run at them with lowered horns through the field. He thrashed about so much that he woke Lizzie who slept in a room next to his, and she, in turn, woke her parents.

In spite of the fact that prayers were raised and many herbal remedies applied, Tom was long in recuperating. His eyes seemed affected and discharged pus. Oozing continually, the boy could not open them. Though the fever had abated after a few days, the infection lingered. Dory, Lizzie, and Philip took turns in sitting with the lad during the day. His father, although often looking in on his son, sat with the boy at night. It became apparent to all of them, after a week or two, that the boy would not regain his sight.

*****

“I have just received a small booklet, Tom.”

The boy was sitting up in bed. Philip, who came and went at will, regarded the boy with affection.

“What is it?”

“It is a catechism written by a man named Alberus, Erasmus Alberus. He wrote it in German and he wrote it for his children. I know that you are rapidly approaching manhood, Tom, but I thought you might like to learn its questions and answers if I repeat them to you.”

Tom nodded.

“Alberus wrote the booklet so that the important parts of Scripture might be learned by rote.”

“Please let me learn also.” Startled, Philip turned and faced Thomas Drourie who stood in the doorway.

“I was not raised with Bible knowledge and often when I read I do not understand what I am reading. Perhaps I can learn with you and we can speak of these matters.” It was a humble confession and Philip was moved. Thomas came in and sat on the edge of the bed. Philip smiled at him.

“Well, it would be fine for us to read and memorize together and I have added some questions and answers myself.”

So they proceeded with simple but very direct dialogues.

Do you love Jesus?

Yes.

Who is the Lord Jesus?

God and Mary’s son.

How is His dear mother called?

Mary.

Why do you love Jesus? What has He done to make you love Him?

He has shed His blood for me.

Has he shed His blood only once or more than once as the Mass teaches?

Jesus has shed his blood only once on the cross at Calvary.

Could you be saved if He had not shed His blood for you?

Oh, no.

What would then have happened?

We would all be damned.

Is God’s only begotten son, the son of the living God, your brother?

Yes.

So you are for sure a great and powerful king in heaven because Christ in heaven is your brother?

That I am, praise God.

How blessed you are! For the Lord has done a great thing for you.

Yes, He has. For He saves a poor, damned child from the Devil’s kingdom and gave me eternal life.

The Drouries all benefited from these and other questions and answers that Philip taught them, and from the many conversations that took place around the bedside of the sick boy.

*****

“Lizzie, Lizzie, I still can’t see.”

“I know. Hush, and lay down. If you move about too much, you will just get sicker again, Tom.”

“Why are you calling me Tom, Lizzie?”

“Well, Master Philip says you are not little Thomas any longer. You have grown so. And I have heard Master Philip call you Tom, and mother and father call you that too now. So I think I will call you Tom.”

“Will I never see again, Lizzie?” The question was uttered in so plaintive a tone that Lizzie sighed.

“I hope you shall but I do not know.”

“You are just being kind, are you not, Lizzie?”

She reached over and kissed her brother. “I shall always be there to be your eyes, Tom. I shall tell you everything I see.”

“It won’t be the same.”

She knew that he was right but was not sure how to respond. “I heard a new pastor preach in the cathedral, Tom. His name is John Hooper.”

“He is not new, Lizzie,” the boy replied, half-sitting up against the pillow, “he has been here for more than a year already.”

“Oh,” his sister said, disappointed that she could not tell him something he did not know, “and how would you have ken of that?”

“Master Philip has told me. He said John Hooper was called to preach before King Edward himself and that the king, who is only four years older than I am Lizzie, very much liked him and then made him Bishop of our city of Gloucester.”

“Oh,” Lizzie repeated.

“John Hooper,” Tom went on, his hands fidgeting with the blanket, “is an honorable man and one who does not like to wear the rich garments that priests and other clergy wear. He says a man should dress humbly, even as your heart should be humble. So you will not see him clad in a chimere and rochet, such as other bishops wear, Lizzie.”

She smiled at her brother and reached over, patting his hand. “You are all about clothing now, are you, Tom?”

He grinned for a minute and then teased her. “And you are not? I have seen, when I could still see, how you constantly preen, Lizzie. And I know you do it for Albert. Only I do not know if father will allow you to marry him. He is, after all, the hired hand.”

Lizzie blushed and was glad for a moment that Tom could not see.

“But Albert is strong and a good lad,” Tom continued, “And…. and I will not be able to help father plough now that I am…. now that I am…. well, now that I might be blind.”

“Hush, Tom.” It was all Lizzie could say, for tears welled up in her eyes.

“Master Philip says that John Hooper, for all that he is the high and reverenced bishop of Gloucester, is a very good man.”

It was quiet for a spell. Lizzie’s thoughts turned to Albert, who was such a dependable young man – a hard-working man, one on whom her father could count. Indeed, she did love him and admired him more than all the young men she knew. But father might object to a marriage, that Tom had indeed said rightly.

“Master Hooper,” Tom’s voice interrupted her contemplations, “has a wife and children, just like our father. His children, Master Philip says, are well mannered. It shames me, Lizzie, now that I lay here on this bed, to think of all the tricks and mischief I set about just a short while ago.”

“Oh, you mustn’t,” began his sister, but he interrupted her.

“Why ever not, Lizzie, ” Tom responded, “for ….” And then he stopped and turned his face to the wall. He did remember with great shame the sorrow he had caused his parents who had been so eager for him to go to school. If his eyes had not been painfully oozing, he might well have wept like a child, for he felt so miserable.

“Tom,” Lizzie’s voice was soft. “Tom, you have been such a good brother to me always.”

Tom swallowed audibly.

“John Hooper,” he went on, his voice shaking a trifle, “is such a man as I would like to be. Perhaps I shall be a preacher, Lizzie. For surely people can be blind and still preach.”

The girl smiled. Although she had great sympathy for her brother, she could not for the life of her picture him as a preacher.

“I know you are smiling,” the boy said, “I can sense it, you minx of a sister! But I mean it. I have done with wasting time. I will ask Master Philip to school me more and more in Bible knowledge. And I also want to go and hear John Hooper preach. Master Philip has told me that at his home there is a table spread in the common hall with a good store of meat. It is daily beset of beggars and poor folk. Every day John Hooper eats with a certain number of poor folk, Lizzie. Is that not a great thing to do?”

The girl nodded, but then remembering that her brother could not hear a nod, spoke. “Yes, Tom.”

“He also questions the poor folk at his table as to whether they know the Lord’s prayer, and the Ten Commandments, and what they believe. And after this he sits down with them and eats.”

“He sounds like a good man, Tom.”

“Yes,” her brother agreed, repeating, “and when I am better, Lizzie, you shall take me to hear him preach. I think he preaches in the cathedral and also betimes on the street.”

*****

It took the greater part of a year for Tom to fully recuperate. Afterwards he walked about with a cane – tapping out the space before him – amazing himself that he was able to recall the steps, the ruts, the holes, the sights and sounds of the farm and thus ascertain where he was. After a few weeks, he ventured into Gloucester. At first, Lizzie guided him. Later his mother accompanied him into town, or he would venture with Philip for a stroll into the country.

The lessons continued. The boy had grown in wisdom as he lay on his sickbed, drinking in the tinker’s instruction with a great thirst. “Why did you not become a preacher, Master Philip?” he questioned his tutor one day as they were strolling.

“I don’t know,” the man answered honestly, “but I do think that God has used me to sell Bibles and to explain certain matters about Scripture to all sorts of country folk as I traveled the roads. These were good things to do and I think that God required it of me. God has tasked me with various matters over the years and right now, methinks, he has tasked me with you, Tom.”

“Well, I am glad,” the boy replied, and then, switching the topic, “I have heard tell in town that King Edward is ill with a fever. Have you heard this also, Master Philip?”

“Yes, I have,” the tinker answered gravely, “and I fear it is common knowledge that our young and good monarch is dying. It is also said that there is a plot afoot to put his eldest sister Mary on the throne to succeed him.”

“Mary?”

“Yes, and I fear that she would return the country to papistry.”

“What would that mean, Master Philip?”

“You know what that would mean, Tom. It would mean that all the things I have taught you over the past year would be condemned as heresy.”

The boy stood still. He seemed dazed. “Tell me more.”

The tinker saw that the lad’s face was serious. “Well, Tom, images and relics would come back; people would be encouraged to kneel to a piece of bread at Mass; and they would be told to confess their sins to a priest rather than to God Himself.”

Phlox was blooming alongside the path. Its perfume was a sugary, sweet scent and Tom recognized it. The smell vividly brought to mind the memory of the pink they were. Alongside their smell, he could detect the faint odor of carrot and knew that, white and delicate, queen Anne’s lace, could not be too far off. Queen Anne’s lace was more commonly called bishop’s weed. Perhaps, Tom thought, if Bishop Hooper had been a plant, he might not have minded wearing queen Anne’s lace. And then he grinned to himself.

CHAPTER 5

In the year that followed, Thomas grew more and more accustomed to walking the roads. History surrounded him as he walked and tapped the cane in front of him. Edward VI died and the brief ten-day reign of Lady Jane Grey followed. Then Parliament, having restored her right of succession, aided Mary to the throne. The Six Articles were reinstated and the citizens of Gloucester learned that their beloved Bishop Hooper had been imprisoned by the new queen. But just before this occurred, to the dismay and horror of the entire Drourie family, Tom was taken into custody. He was thirteen years of age.

Thomas’ arrest happened quite suddenly. Walking across Westgate Bridge one early morning, carefully tapping out his steps, he met Father Serly. Father Serly, still short and stout had survived Edward’s reign by outwardly conforming to Protestantism. However, as soon as Mary ascended the throne and papist rules were back, he emerged ready to wage war on anyone who was not attending Mass.

“Thomas Drourie,” he called out, as the blind boy was about to pass by him.

Thomas stopped, recognized the priest’s voice, but answered nothing.

“I have not seen you at Mass of late,” Father Serly went on, using the very same words he had spoken to the boy’s father more than a decade past.

“No,” Tom agreed.

“Have you been ill? Has there been no one who could guide you?” The words were friendly enough, but there was underlying threat. Tom perceived it. His father made no secret of the fact that he disliked Father Serly and a great many of the other priests. He was also fully aware that the Cathedral had reverted back to papistry and that many Protestant Englishmen had fled England.

“Well, Tom?” As the boy still did not answer, the priest assumed that perhaps the lad did not know it was a priest he was speaking with.

“I am your Father,” he said, somewhat loftily.

“I have only one Father,” Tom then replied, “and He is in heaven.”

“Are you being rude, young sir?”

But Tom stood quiet again, and there was no sound but the water of the Big Severn rushing underneath the bridge. Deciding not to continue in conversation with the priest, he began tapping out his steps again, walking forward as he did so. The stout cleric blocked his path.

“I asked you a question, young Thomas Drourie.”

The boy laughed and pushed at the black robes preventing his leaving. He was young and blind, but he was strong and his shove succeeded in thrusting the priest against the side of the bridge. Not only that, but the motion caused the friar to fall down on the slats amid the laughter of some local folk crossing over from the other side. Humiliated, the priest complained to the town’s guard and the result was that Tom was taken into custody for an overnight imprisonment. His father had to pay a hefty fine the next morning to have the boy released.

*****

“You must not be so bold, Tom” Lizzie was sitting on a bale of hay next to her brother. “You could get father and mother into trouble by such behavior. You would not want that.”

Her brother shook his head. “No, of course I would not.”

“Well, then, you must stay at home and if you want something, either I or Albert will go with you into town.”

“Philip has told me that Master Hooper was arrested, Lizzie. He is being kept in Fleet Prison in London.”

“Yes, that is true.” The girl spoke softly, knowing that Tom looked up to the man, admired him and would feel badly about the news.

“He probably,” Tom went on, “has no family who can set bail for him as I have heard that his wife and children have left England. The queen, Philip said, wants him dead.”

“Oh.” It was all that Lizzie could think of to say. She was seventeen now and a beauty with long brown hair, just like her mother. She and Albert now had an agreement between the two of them. He had of late, spoken with her father. For a moment she forgot the young brother sitting next to her on a bale of hay. Albert was almost thirty now and she knew that during the conversation he’d had with father he had not been refused. Father would have to weigh the facts and these were that Tom would never be able to run the farm on his own; that Albert was an honest man who truly loved Lizzie; and that Albert also cared for Tom. She glanced at the boy sitting next to her. He was staring straight ahead. But surely it must be at something within himself, for his eyes saw nothing in the barn. Albert took him ploughing in the fields, had him walk by his side, explained what he was doing, always included him in conversations about planting, harvesting, and caring for the cattle. Could they not all live in harmony – father, mother, Albert and herself – caring for Tom and for the farm?

“They say,” Tom interrupted her thoughts, and speaking vehemently, “that those who put Bishop Hooper in prison accuse him of owing the queen money. But it is not true. They are lying about him.”

“Hush, Tom! Do not take on so.” Lizzie put her right arm about Tom’s shoulder as she spoke.

But Tom went on, his hands striking the air in anger. “The real reason, Lizzie, is that they want him dead. They want him dead because he is a Protestant just like we are.”

She was slightly alarmed at his words.

“The heresy acts have been revived,” Tom continued, his voice somber now.

“We just have to stay on the farm, Tom,” Lizzie answered, “We won’t get involved. Father and mother don’t go into Gloucester very much anymore and we have all we need right here.”

“There is a rumor, but I think it is the truth,” the boy went on, “that Bishop Hooper will be transferred to Gloucester at some point. When he is, I want you to take me to his place of confinement, Lizzie. Will you promise me that you will?”

Lizzie did not answer.

“Well, if you will not take me, then I shall ask Master Philip or Albert.”

“No, not Albert.” Lizzie’s answer was swift now.

“Well, then?”

“Yes, Tom. If and when Master Hooper comes back to Gloucester, I shall take you to see him, if that is possible.

Satisfied, the boy leaned into her shoulder. “You are a good sister, Lizzie.”

*****

Approximately two months later, in February of 1555, word came to the citizens of Gloucester that their former bishop, John Hooper, would be taken, under heavy escort, to Gloucester. It was Philip the tinker who recounted this to the Drouries at noon.

“Actually,” he went on, glancing at Tom’s white face as he spoke, “he was taken to Gloucester today. Although the news of his coming was kept secret, it leaked out. A mile outside town, I saw crowds assembled – men and women all crying and lamenting Hooper’s sorry state as he passed.”

“You were there? You saw him?” Tom asked.

“Yes, I did, Tom. I watched as one of the queen’s guards, and there were six of them for the one man, rode into Gloucester to ask for the aid of the mayor and sheriffs. These namby-pamby guards were worried that Hooper would be rescued by the people standing at the side of the road. I saw a great many officers armed with weapons come to the North Gate. They ordered the people to go home and to stay home and then conducted John Hooper to a place where he will be kept until…. ” He left off and it was quiet.

“Until what?” Tom finally threw out.

“Until his burning at the stake tomorrow.”

There was quiet around the table. Lizzie, who sat across from Tom, felt his foot kick her shin. She winced slightly, but she knew what it meant.

CHAPTER 6

They managed to leave the farm together under the pretext of visiting one of Lizzie’s friends.

“I don’t know where to take you, Tom, for Philip did not say where they lodged the bishop.”

“You must take me to the Cathedral, Lizzie. For at that place they will know of a certainty where he has been taken.”

“Even so, Tom, why should they tell you?”

“Because they will.”

“Well, I will take you. But you must promise me to be careful.”

The boy did not answer and they walked along in silence, the boy tapping his path all the while, his cane in his right hand and Lizzie holding his left.

When they arrived at the Cathedral, the Gloucester streets lay still. The people had been ordered to stay indoors.

“Take me to a side door, Lizzie, and I will knock. You need not stay. But do not go too far either.” His sister brought him to a nether door and the boy began knocking almost before she had time to find her way around a corner. Tom knocked loudly and persistently and at the beginning no one came to answer. But he continued in fervor, scraping his knuckles on the wood. At length, a guard opened the door.

“What do you want, boy?” His voice was not unfriendly and Tom took heart.

“I want to see Bishop Hooper.”

The guard was taken aback for he could see that Tom was blind.

“Please sir,” Tom repeated, “can I speak with the Bishop to hear his last words to me before he goes to the stake.”

“Are you family?”

“Yes, he is to me as a father.”

The guard, who was not a bad fellow, relented upon hearing the earnestness in the boy’s plea. “Very well, then, come along.”

“You must give me your hand, sir.” Thomas reached out and the guard took his hand, pulling him inside the building.

“Come along then and tell me your name.”

“Tom Drourie, sir.”

The guard walked along a corridor, talking the whole while. “My name is Edmund Wells, Tom, and it is a sad business, this whole thing, is it not? But your name sounds familiar. Was there not a boy named Tom arrested a short time ago for….”

He stopped, scratched his head, and then smiled. “Yes, now I remember. It had to do with Father Serly, a man I care little about. If I recall correctly, it was because this certain Tom had pushed him.”

“Yes, sir.” Tom answered softly, hoping the conversation would not cost him his chance to see Bishop Hooper.

“Well, Tom, if that was you, I would not take it to heart. Father Serly is…. well, he is not overly truthful and he is much concerned about himself. But be careful what you say, boy, for these are treacherous times.”

Tom nodded and the guard talked on.

“Bishop Hooper will be taken to Robert Ingram’s house later today. He’s not to stay in a common gaol, that good man, but in a home where they respect him. So that is a blessing. And now we have come to his cell. I must let go of your hand to open the door with a key. There’s a good lad. Just stand here.”

Thus speaking, the guard opened the door before returning to Tom. Reaching for his hand, he propelled him inside a small room.

“Here’s a young lad come to bid you good day, Master Hooper. Says his name is Tom – Tom Drourie. I believe Tom was arrested a while back as well for speaking disrespectfully to a priest. I’ll collect him by and by.”

With that he shut the door and Tom was alone with the bishop.

*****

It was a small room. Tom could feel the walls close and the ceiling low. He stepped forward hesitantly, tapping his cane carefully. “Good afternoon, sir,” he finally said, his voice small and thin.

“Good afternoon, Tom,” he was answered by a friendly and low voice, “and what brings you to visit me here in this sad place?”

“I wished to say….” Tom began, “I wished to say that I will pray for you, sir. It must be dreadfully…. dreadfully….” He could not go on and a moment later felt a hand on his shoulder.

“There, lad,” both Bishop Hooper’s voice and hand guided him along, “Here’s a chair. Sit yourself down and we shall have a talk, you and I, and find out what is in your heart.”

Tom breathed in deeply, ashamed that he was blubbering like a child again. “Thank you, sir,” he managed.

“Well, Tom,” the bishop continued, putting him at his ease, “I’ve a lad just like you at home. Only he’s left England and I don’t get to see him any more. I miss him very much and so appreciate your visit for that reason alone. If I had my lad here, I would counsel him to hold fast to the faith.”

“Yes, sir,” Tom responded, his blind eyes fixed upon the direction of the voice.

“Do you believe in the Lord Jesus, son?”

“Oh, yes, sir.”

“Do you confess His one sacrifice on the cross and deny the popish idolatry in the Mass?”

“Oh, yes, sir,” Tom breathed out again.

“Well, lad, then there will not be a goodbye between us once the guard comes to take you back. For of a verity, we will see one another in heaven.”

“Do you think I shall see?” Tom ventured, “in heaven.”

“Yes, Tom, you certainly shall.”

There was a long quiet, but it was not awkward. The bishop had taken the boy’s hand into his own. After a while he spoke again. “Ah, Thomas! Ah, poor boy! God has taken from you your outward sight, for what consideration He best knows. But He has given you another sight much more precious, for He has induced your soul with the eye of knowledge and faith. God give you grace continually to pray to Him that you lose not that sight, for then you should be blind both in body and soul.”

Tom nodded, his eyes again filling with tears. At that moment the door opened with a groan of heaviness and disuse.

“Tom, time to go.” It was Edmund and Tom stood up.

The bishop clapped him on the shoulder. “Son, may God bless you and keep you and let His face shine upon you and be gracious unto you.”

Taking Tom’s hand, the guard steered him towards the hall and all the while Tom was mindful of the lark in the field where he had been with Philip. And he recalled with great clarity how the bull had charged and how Philip had played the viol.

Walking back towards the entrance, Tom begged Edmund for permission to hear Bishop Hooper speak prior to his being burned at the stake. For so it was that condemned men were allowed to address the crowd prior to being martyred. Without a word, the man took the boy through to another anteroom, one that led into the cathedral. Although Tom could not see it, this was the place in which Dr. Williams, the Chancellor of Gloucester, was sitting behind a desk. The registrar sat next to him and they were concentrating over some paperwork. Without waiting for permission, the guard spoke.

“This boy wants permission to hear the bishop speak tomorrow before his martyrdom.”

“Martyrdom, Wells?

“Whatever it pleases your Honour to call it,” the man answered, before he turned, leaving Tom in the sanctuary.

Dr. Williams, who was a heavy-set man, turned from the paperwork to peer at Tom. “What is your name, boy?”

“Thomas Drourie, sir.”

“And you wish to see Bishop Hooper die?”

“Not die, sir, but live.”

“Are you a good Christian, Tom?”

“I try to be, sir.”

“Hmmh,” the chancellor said, and glancing at the registrar added, “Well, suppose we ask you some questions as to ascertain that.”

Tom stood in front of him, cane in hand, eyes fixed on where the chancellor’s voice came from.

“Do you believe,” the chancellor began, “that after the words of the priest’s consecration, that the very body of Christ is in the bread?”

Tom responded strongly with a very loud, “No, that I do not!”

Dr. Williams looked keenly at the disabled boy in front of him. “Then you are a heretic, Thomas Drourie. Do you know that for this reason you can be burned? Who taught you this heresy?”

Tom, the eyes of his heart bright, even though his outward sight was dull, answered clearly, “You, Mr. Chancellor.”

Dr. Williams sat up straight. “Where, I pray you?” The words echoed hollowly through the sanctuary.

Tom replied softly but clearly, pointing with his cane towards the place where he supposed the pulpit was, “In yonder place.”

Dr. Williams was aghast. “When did I teach you so?”

Tom, now looking straight at where the chancellor’s voice was coming from, replied plainly and distinctly: “When you preached a sermon to all men, as well as to me, upon the sacrament. You said the sacrament was to be received spiritually by faith, and not carnally and really as the papists have heretofore taught.”

Dr. Williams looked down at the papers in front of him. He felt a certain shame in his heart. Nevertheless, his voice boomed out and resounded in the aisles. “Then do as I have done, and you shall live as I do and escape burning.”

Aware that the bull was charging, but hearing the viol, Tom answered calmly and firmly: “Though you have easily dispensed with your own self and mock God, the world, and your conscience, I will not do so.”

Dr. Williams was vexed, vexed in his soul. Although he tried for some time to convince the boy otherwise and threatening him plenty, there was no recantation. Finally, he bellowed: “Then God have mercy upon you, Tom, for I will read you your condemnatory sentence.”

Tom answered, “God’s will be fulfilled.”

At this moment the registrar nudged Dr. Williams. “For shame, man! Will you read the sentence and condemn yourself? Away with you! At least substitute someone else to give sentence and judgment.”

But Dr. Williams would not change his mind. “Mr. Registrar!” he barked out, “I will obey the law and give sentence myself according to my office.” After this he read Tom his death sentence, albeit with a shamed tongue and a twisted conscience.

“Wells,” he then cried out, for the guard was present once again, “take this boy to a cell.”

“Sir, I beg you,” a small voice cried out in the back of the sanctuary, “have mercy on my brother.” It was Lizzie who had been let in by the kindhearted Edmund.

“Do you wish to be arrested alongside your brother?”

“Sir, I would feign take his place if it would help his case.”

Tom felt love well up in his heart for his sister. Often she had kept him from wrongdoing in the past; often she had nursed scraped elbows and bruises; and often she had comforted him after he had been lonely. She was like a second mother. Ah, his mother! Tears sprung to his eyes. He had not thought of his parents this whole time. Lizzie slowly lifted one foot in front of the other, as if she were gathering courage in those unhurried steps, and approached the front, standing right before Dr. Williams.

“He is but a lad, your honor,” she haltingly began, “and his mother ….”

Then she wept. Tom was at her side in an instant. “Don’t cry, Lizzie,” he pleaded, “please don’t cry.”

“How can I help it Tom?”

“You will see me again, Lizzie.”

She lifted her tear-stained face towards him, doubtful and hopeful at the same time.

“Tell mother and father that I shall be home shortly, Lizzie. And tell them that I look forward to that homecoming more than anything else.”

Then Edmund Wells took the boy’s hand in his own and led him away.

*****

A true story, flavored with fiction, the blind boy Thomas Drourie (together with a bricklayer by the name of Thomas Croker) was burned at the stake on May 5, 1556. This was three months after Bishop Hooper was burned. Three years later, during the early years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, Chancellor Williams poisoned himself, thus adding suicide to his previous crimes. For Thomas Drourie, Bishop Hooper and other faithful believers, there was the light of God’s countenance; for Chancellor Williams, what shall we say?