The smooth money resting in John’s calloused hand equaled his small plot of land; a few acres lay on a roughened palm. It had only been a barren, untidy patch at best really – just enough to keep some geese and, when times were good, a cow. It had yielded enough to keep one from starving – not enough to keep one satisfied. It had been a way of life for John’s father and grandfather. And they had survived.

The land divided into strips and was owned by very poor farmers, by verge-of-poverty peasants. Inevitably, big, neighboring landowners coveted these strips – these pieces of thin but still independent existence. For a few guineas, John Spence had given up his meager plot, his paltry inheritance. Those guineas lay in his weathered palm. The money wasn’t much, yet it was more than he’d ever had. But it wasn’t enough to buy more land, no, not enough to buy more land.

John regretted the agreement almost as soon as he was sober. The facts, however, which had driven him to drink and to the sale of land, were still just as compelling: his wife big with another child and food scarce.

There was also another reason. A seemingly small enough reason, to be sure, but a reason that nevertheless had taken root and had given the final push to the matter. That reason was a tiny whisper of greed in John’s heart of hearts. There is, the whisper said, money to be made in factories – city factories – London factories; much more money than you’ll ever pull out of your half-penny patch. The drinking in the taproom had tempted him with this thought many times before. But never until now had it been so inviting and so obviously right, and never until now had he acted on it.

Now that the deed was done, the possibility of work on the bigger farms as laborer for a shilling a day also existed. But a shilling was a pittance. Kate could work the fields too, but she’d nearly died at the last birthing. No, right or wrong, John’s heart had sold itself to what he thought the city could offer. So they moved – John Spence, Kate Spence and Annie, their only surviving child, twelve this mid-summer.

And such was the weight of their poverty, that they wore all they owned.

***

“Just you wait, girl.” John spoke as he supported his wife, as they picked a slow path over the ruts and puddles of bad roads. “London will ‘ave us sittin’ fine and proper. Why this babe will ‘ave that silver spoon in his mouth. Just you wait, girl.”

If Annie listened avidly, Kate didn’t hear a word John said. She was too weary, too heavy and she hated sleeping in the hedges.

“There’s many a job to be ‘ad,” John went on, looking at Annie when Kate didn’t respond. “I ‘urd from one lad they’re just cryin’ for strong labor.”

His spirit was hopeful and his mind entertained thoughts of fortunes. Annie believed every word he said.

“Can I git a job too, Da? Can I?” She danced in front of him, her soft, brown hair waving, minding him of a young foal.

“Well, Annie girl, I’ve ‘urd of basket weavin’ and work at mills and such. We’ll see.”

Annie laughed. Da and she – they’d make a home for Mum and the new babe. And they kept on walking, Kate Spence great with child between them, paving the way to London with good intentions.

***

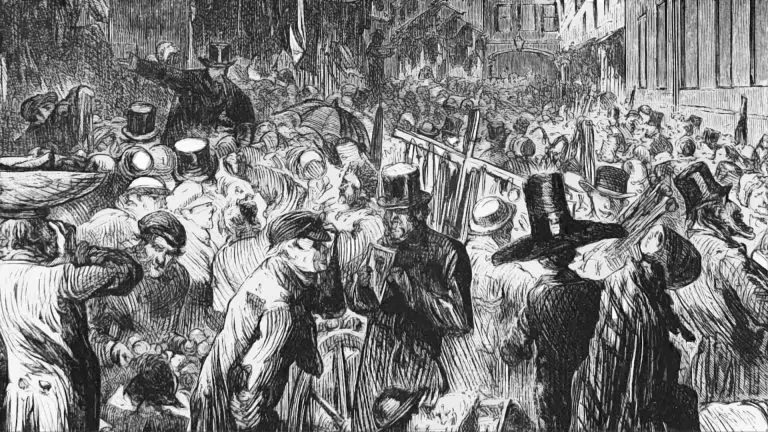

London could be smelled before it was seen. The stink hit the Spences before their feet touched its intimate roads. Then they were caught up in the noise and crowds that flooded the city’s muddy streets. Aimlessly they were moved about. A motley assortment of people and things jostled them as they walked – bearded Jewish old-clothes vendors, organ grinders, cabmen’s wheels, costermongers selling their wares, and flower girls bawling at the top of their lungs. Overhead smoke rose, darkly coiling from a few million chimneys, while St. Paul’s Cathedral’s bells bonged overhead. And not a green patch in sight, but the small patch in John’s memory.

John Spence was confused. He did not know the ways of London and did not recognize its throb of misery and clamor. “We’ll see if we can’t find a place to sleep for the night.” He stumbled, weary with the days of travel. Foul water and refuse ran past them in a gutter down the middle of the road.

“Buy! Buy!” The cry of the vendors was deafening.

Kate leaned against him helplessly. “There are no ‘edges here, John. Wot will we sleep in tonight?”

“Da! Da!” Annie pulled John’s hand. “There’s a lad ‘ere says ‘is mum ‘as rooms to let.”

John turned to look. A boy, face streaked with dirt, grinned at him. “Foller me, sir.”

They followed him. There was little choice. Mazes of alleyways coughed up houses more rough and tumble at each turn. They avoided the beggars hunched forward in doorways. They stepped past the sick lying next to the gutters. They breathed in the smell of turpentine, leaking gas, sewage and sweat. In the back of John’s mind the barren strip of lost land became more fertile and the smell of growing things flooded his soul, but he could not undo time as one undoes a knot. So he walked on and his family walked with him. And the boy walked ahead of them. Kate was slower than ever now, clinging to John for support. Clusters of tumbledown houses were built around filthy courts. The boy stopped in one of them.

“Ere’s where I live. I’ll call me mum.” He disappeared up a flight of rickety stairs and came back a minute later with a limping, tall, fair-haired woman. Her voice was low.

“Ear you’re looking fur a place to stay. I’ve got rooms.” She took in all three of them with a curious look. “Can you pay?”

John nodded confidently and reached into his pocket. He withdrew his hand seconds later with a look of horror on his face. “Kate!! The munny… it’s nowt ‘ere!”

But Kate didn’t hear him. She was too tired, too hungry and slowly crumpled to the ground in a heap.

***

Susan Jarrett was shrewd in the ways of the poor. She took the Spences in on what she termed “trust.” Besides, her son was a virtuoso in pick-pocketing and the contents of John’s pockets had already been counted out on her table. Had she not taken them in, the Spences would have had to huddle together for warmth under a bridge, or in a churchyard, or perhaps in a shop doorway. And with Kate so near her time, it would have been murder. Not that Susan Jarrett would have had qualms about that, but she instinctively felt there was more money to be made and she wanted her share of it.

The room Susan showed the Spences was bare, but it did provide a roof over their heads. A few flour bags furnished a scanty mattress. There was a tiny window, but no water or any other convenience. The only water tap available was a few doors down and this had to serve all of the thousand-odd tenants who lived in that particular court. As for toilet facilities – fifty to sixty people shared two earth-closets.

***

John was quiet that next morning. Brooding in a corner of the room, his back was hunched against the wall. More than once he had rechecked his pocket, unable to accept the fact that now his money, as well as his land, was gone. His usual cheer had shriveled up in this skyless place. Moodily he surveyed Kate sleeping on a flour bag and thought of the children they had lost. It wasn’t likely this babe would survive either. As for the silver spoon, he grimaced bleakly to himself. All he wanted presently was shelter and food in exchange for some hard work – no more. Was that wrong? Or, and his mouth worked nervously at the thought, had he sold away their very lives? He got up suddenly and moved towards the door.

Annie eyed him questioningly from her place on the floor. “Where are you off to, Da?”

He forced a smile. “Got to git sum work to feed you and your Mum, Annie girl.”

He was gone before she could ask more. Kate moaned. It would be her time soon. Annie had helped before.

***

John walked and walked. He kept his bearings, determined to find his way home again later. Passing along the polluted edge of the Thames, he watched “mudlarks” – boys who waded into the filthy mud at low tide searching for scraps of iron and lead to sell. If they were lucky, they’d make a few pence to take home to their families. He saw them crouch under the bridges, scraggly, skin-and-bones scarecrows. And he took note of other children sweeping the road clean for any lady or gentleman who wished to cross a begrimed spot, hoping for a charitably thrown halfpenny.

What kind of life was this? John clenched his farmer’s fists, yet again cursing the day he had sold his land. But it was a helpless curse, as indeed, all human curses are helpless. Black words which do nothing to change a situation. It was always the poor against the rich and who was he? And what now? Kate hungry and cold – Annie hungry and cold – and he, who was he? The streets, full of sellers and buyers, seemed to jeer at him. And he walked all day without finding work.

There was no joy in the thought of going back to Kate and Annie – Annie with the hope shining clear out of her eyes. He had no desire to retrace his steps through the winding alleys back to the naked room.

And then the evening dusk coughed up a tall, black-bearded man in a dark frock coat and wide-brimmed hat. The man was standing directly in front of the tavern that John had unconsciously been heading for. There was no money. There was only the desire for other men’s company – for those who, like himself, were also without work, without food, without money and without hope.

The bearded stranger pulled out a book and began speaking. Faces appeared at the pub’s windows. “There is a heaven in East London for everyone,” he cried, “for everyone who will stop and think and look to Christ as a personal Savior.”

The words did not mean much to John but the deep voice did carry warmth and conviction. From the pub’s doorway a rotten egg flew through the air, almost hitting the wide-brimmed hat. The man stopped speaking and walked on. Bystanders howled with laughter. John’s curiosity had now been aroused. Clapping someone on the shoulder, he asked who this man was.

“Ey, watch out! Tryin’ to pick me pocket, ain’t you?” Drunken, sour breath hit him, disgusted him and bitterly reminded him once more of the land he had lost.

The wide-brimmed hat was coming his way. John regarded the tall figure intently. To risk being heckled and hit with rotten eggs, the fellow must surely believe in whatever it was he had been trying to say. But then, people were always talking, always bent on persuading others of their point of view. His gaze dropped. What was this man to him, or he to the man, for that matter? Unaware of John’s thoughts, however, the man stopped when he reached John, his eyes kind and penetrating.

“You’re hungry.” It was said in a matter-of-fact voice even as his hand reached into a deep pocket, coming out with sixpence. “There’s a place where you can buy dinner with this. I’ll walk with you.” And there was such persuasive authority about the man that John went with him.

They passed a number of pubs. By the light of gas jets, men’s inflamed faces drifted by. Jeering and drunken women stood propped up against soot-drenched houses. The reek of gin and sweat mingled. Even in the shadow of a benefactor, John felt discouragement descend on him like a heavy, suffocating cloak. Where was he going and how would he ever manage to take care of Kate and Annie and the new baby in this place?

The man did not speak as they were walking. Yet a certain affinity was established as they trudged side by side. Every fifth shop they passed was a gin shop. Glancing in John noted the special steps most of these shops had to help even toddlers reach the counter where penny glasses of colored gin could be ordered. Small, misbegotten tykes lolled about on the floor of some of these shops – by-products of alcoholic parents who had nothing else to live for.

“Here’s where you can eat.”

“Thank you.” John did not know what else to say.

“Are you hungry for peace of mind too, man? Are you tired of drinking and such?”

John looked at his benefactor doubtfully. Sure he was tired of drinking and wanted peace and food and work and shelter and… he could go on and on. But there was surely more to it than just saying “yes.” Answering shortly, he summed up his whole life in just a few sentences. “I’m new in London. Walked in from the country yesterday. I ‘ave a pregnant wife and a small dotter.”

Rather hopelessly he added a last bit of information. “And all the munny I ‘ad was stolen.”

“What’s your name?” The stranger regarded John keenly as he spoke.

“John Spence.” He almost spit the words out. They sat like gall in his throat. He so despised himself for what he had done.

“Well, John Spence, would you like to come to a meeting tonight that might change your life?” As he spoke, he pointed to an empty pub across the way. “I hope to see you there after you eat.” Then he shook John’s hand and disappeared down the road – vendors, fog and houses alike swallowing him up quickly.

***

The dinner was good. John wolved it down even as he guiltily thought of Kate and Annie with every bite. But he’d have to keep up his strength in case there was work to be had. He put a hunk of bread into his pocket as he washed down his last mouthful. He could see that a crowd had gathered across the road in the pub and appeared to be listening to a speaker.

John wandered over, curious to hear what was being said. Listening cost nothing and would put him under no obligation to anyone. There was no one who took special notice of him as he took his place on an empty bench near the back. The speaker’s piercing voice cut through the room and a long finger pointed convincingly to the door John had just passed through.

“Look at that man going down the river.” The voice had risen a decibel, ringing the length of the pub. John turned to look, as did everyone else, even though all knew there was no river.

“Look at him going down in a boat with the falls just beyond. Now he’s got out into the rapids… now the rapids have got a hold of the boat… he is going, going…” The voice rose again. “He’s gone over – and he never had a chance.”

There was a dramatic pause before the finish.

“That is the way people are damned. They go on; they are caught by the rapids of time; they don’t think; they neglect God; and they are damned. Oh, you who are the Lord’s, seek Him while He may be found. Call on Him while He is near.”

***

Through the maze of alleyways John found his way home late that night. The different twists and turns all looked and smelled alike in their filth and squalor. As he finally trudged up the stairs, he was met by Susan Jarrett. “Your wife ‘ad ‘er little ‘un.”

Pushing past her, John ran the length of the miserable corridor. The smell of birth met him. Kate lay on a filthy sack in the corner and by her sat Annie, on the floor, holding a small bundle wrapped in a coarse cloth.

Annie did not look up as her father came in. It was only when he touched her shoulder that she moved her head. Then it was woodenly. And her voice cracked when she whisper-said, “Mum’s dead and so’s the babe, Da.”

Then John cried. It was a bitter, raw cry – a loud, wailing cry – and it brought the other tenants to his door. But they could not help. Every room in the court housed a poor family, and they were all dirty and hungry. Brief in their sentiments, they were briefer in their stay. The only one that remained behind in the end was Susan Jarrett. She wanted to know if the rent was going to be long in coming.

Tonelessly John replied, “I’m off fur some work tomorrow.”

“Your dotter’ll ‘ave to stay ‘ere.” There was finality in her tone.

“It’s all right, Da.” Annie’s voice was soft. She stroked his arm. “It’s all right.”

He looked at the small bundle she was still clasping and at the inert form of Kate on the sack. There was no world anymore. Or was there? Annie’s soft, brown hair hung about her oval face. Incredibly she smiled at him. Flooding over him suddenly was the memory of the man who had given him sixpence and who had spoken kindly.

***

The tiny window glimmered faint light that next morning. Annie woke up with a strange sensation within her deepest self. It was not hunger. She knew hunger – it could gnaw in her stomach and hurt. No, this was different. This was grief and this pulled at her heart, weeping and tearing at her soul. It was agony – agony that could not be abated or turned into gladness. Annie swallowed thickly and peered through the thin darkness for Da’s form. But there was no one in the room with her. Da had told her last night that he would be up and away early trying to find work. “Rest easy tomorrow, girl,” he had said, “I’ll be back. Don’t you fret! I’ll be back.”

Someone had taken Mum’s body and the babe’s too, tiny though it was. And Susan had taken away the sacks, hardened with Mum’s blood, Mum’s life. And now there was nothing. Annie sat up. She was cold. Da had given her a hunk of bread last night and she fingered it absently.

It was like that for the next three days. Annie stayed in the room by herself. She walked about a bit, filtering sunlight between her fingers when sunlight hit the tiny window. And she cried often, sleeping between tears, weary with an immense burden of grief. She ate the scraps of food that her father brought her from his haunts around the city. He was not much for talk in the evening. Annie tried to read his face as he sat dejectedly against the wall. Sometimes she would rub his arm, as a kitten might rub up against a leg, she was that starved for affection. Then John would start, looking at Annie with a mixture of guilt and love.

“Never mind, Da,” she would whisper, “we’ll manage. I’ll take care of you.”

There was a pain in John when she mouthed this and he ran his rough right hand through her fine, brown hair and pulled her close with his left. She snuggled by him, feeling somewhat comforted, yet also aware that she was being a comfort herself.

***

It was on the morning of the fourth day that Susan came into the room unexpectedly. Annie’s heart thudded. Susan had not bothered overly much with them. But they were in her debt; they owed her the rent. Susan spoke from the doorway: “There’s a lady downstairs says she might ‘ave a job for the likes of you. Wants to ‘ave a look-see at you and a small chat.”

“A job?” From her spot on the floor Annie looked up at Susan dumbfounded.

“Right. A job I said. Now get up then and come down with me.”

“What sort of job?” Annie shook the ragged garment that had once been her mother’s dress and then wiped her fingers on the edge of her skirt as she stood up. Susan didn’t answer but motioned for her to come, turning back into the bleak corridor. Although apprehensive about offending, Annie repeated her question as they walked down the stairs. “What sort of job?”

“‘elpin’ with ‘ousework. Easy work, that. And you get plenty to eat.”

Annie hadn’t been eating much and her small stomach revolted when she walked into the cramped, one-room living quarters where Susan managed with her three children. A smell of fried onions and fish hung about nauseating her whole being. There was a woman in the room, a handsome woman in a rather coarse sort of way. Looking steadily at Annie, she suddenly smiled.

“My name is Mrs. Darcy.”

“My name is Mrs. Darcy.”

Swallowing down the bile that had risen to her throat upon entering the room, Annie smiled back. She had to force the smile. She missed Mum and hadn’t talked to anyone for days.

“I hear you’ve just come in from the country?”

“Yes.”

Mrs. Darcy, who wore a brown ulster and had a lace shawl draped over her hair, smiled again. Annie thawed under these smiles. With but little prodding Annie told both Mrs. Darcy and Susan her life’s story, which took only as long as it takes a dog to wag its tail before it gets a bone.

“I need a girl to help with some light work around my house, Annie,” Mrs. Darcy said when the girl had finished, “Do you think you’d care to have the job?” Seeing Annie’s hesitation, she added, “Of course, you’d be earning a wage. Fair’s fair, right? How does four shillings a week sound?”

Still Annie wavered. “Me Da,” she began.

“Listen,” Susan said from where she stood in the doorway, “wouldn’t it be fine to surprise your poor Da? Suppose Mrs. Darcy comes for you tomorrow mornin’. I’ll make sure it’s fine with your Da when ‘e comes ‘ome tomorrow night. See, ‘e might not want you to work, girl, ‘im being such a good Da and all, but I know you want to ‘elp ‘im out.”

Annie took a deep breath. “Can I see ‘im Sundays?”

Her voice was soft. The two women glanced at each other. “Sure, and I’m sure you could. Why don’t you ‘ave all your belongin’s packed together in a bundle and be ready for Mrs. Darcy in the mornin’.”

“I ‘ave no belongin’s except this.” Annie indicated her threadbare, thin frock.

“Well then,” and Mrs. Darcy responded as if it were a normal thing, “we’ll just have to see about getting you something better.”

Annie moved towards the door, ready to go back to her room, but Susan stopped her. “Why not go out and sit on the steps for a bit. You’ve been in such a long time and you’re such a good girl, Annie. I’m sure your Da, ‘e wouldn’t mind.”

The sunshine was pleasant. Annie squinted in the bright warmth of the day. Wouldn’t Da be surprised and right pleased to hear that she had a job. And new clothes! Although maybe the woman would only get her an apron. But even that would be pleasant. Wouldn’t Mum have been proud to see her in something decent! She fingered her worn skirt absently. Perhaps today Da would come home and tell her that he had a job too. That would be even better. With deep intuition she knew that Da needed to have a job more than she did. He needed it to keep his self-respect. The sun shone warmly and at this precise moment she was sure that things would end well. She surveyed her surroundings, soaking up the rays. Ah, but things were dirty here in the city. The gutter carried slop and there was a small nipper crawling in it. They had been poor as long as she could remember, but Mum had always made sure that she was clean and Mum had never let her muck about in the dirt like that.

“‘Ello.”

Annie startled. There was another girl at the bottom of the steps quietly eyeing her. “‘Ello,” she offered back with a timid smile.

“Your new ‘ere then? My name’s Eliza. What’s your name?”

“Annie.”

“Wot your doin’, Annie, sittin’ ‘ere in daylight. Got no work then?”

“I’m startin’ work tomorrow.” There was so much pride in Annie’s rejoinder that the other girl laughed.

“That so? I work in a factory. That is, I did work in a factory. It shut down. Wouldn’t mind so much but the munny see, we need the munny.”

Annie nodded. She understood that. Eliza continued. “We used to live down south of ‘ere. It was in a coal-minin’ town. Mum took us, Tansy, Maude and me, down into the pit early in the mornin’. Carried baskets on our shoulders. When we got way down the men would fill our baskets with coal, big ‘eavy pieces they was, and we’d go up agin. Dark it was in them pits.” Eliza shivered involuntarily.

Annie did too and asked, “‘Ow did you see in them dark pits?”

“Oh, me Mum, she’d ‘ave a candle between ‘er teeth. We’d foller ‘er. At the top we’d empty the coal and then go down fur another load. We weren’t allowed to rest ever.” She emphasized the last word and spit on the ground after she said it as a gesture of contempt.

Annie took a hunk of bread out of her pocket. Da had given it to her the night before. “Want to ‘ave sum?”

Eliza’s troubled look disappeared. She grinned broadly. “Sure.”

***

Da was quiet again that night. Annie was sorely tempted to tell him about her job but remembered what Susan had said and did not. She did kiss his stubbly cheek telling him things would be better, no matter what. She told him too that she’d been allowed to sit on the steps and that she’d made a friend. She could see Da begin to relax a bit and thought of how happy he would be when she gave him her first wages.

“I’ve been goin’ to sum meetin’s.” Not looking at Annie at all, John spoke softly, almost to himself.

“What meetin’s Da?” Annie was interested. Her father rarely informed her as to how he spent his days.

“Well,” John shifted his position against the thin, cardboard wall, coughing and thinking simultaneously. He wasn’t too sure about his subject matter. “Well, meetin’s where they tell you about Jesus and ‘ow to live.”

“You mean your goin’ to a church, Da?” Annie was awed. Back home church had only been for the rich – only for those who had proper clothes to wear. Mum had told her a bit about how God wanted people to live. She understood that God wanted you to do things that were right – things like not stealing, not cheating and not using bad language. Her father’s voice stopped her train of thought.

“No, Annie. No.” Shaking his head, not at all familiar with the vernacular on which he was about to embark, John continued hesitantly. “Not likely the church back ‘ome would allow sum of the men I’ve seen in these meetin’s to come. The people that go are poor, Annie. Just like us.”

“Where’s these meetin’s, Da?”

“Well, I’ve been to three and they’ve all been in a hall.” He grinned a bit as he spoke and went on. “They call it a hall, but it’s really a pub.”

“A pub?” Annie was incredulous. “Why, Da? That’s not a real church.”

“Annie,” John Spence turned his head to face his daughter directly, “many’s the time I thought God cared nowt fur me. I didn’t blame ‘Im. I didn’t care fur ‘Im either. I cared fur drink. But I did work ‘ard on the land.” He stared down at his hands and went on. “But I just warn’t important. I ‘ad no munny. Anyway, munny don’t count, Annie.”

He stopped, not certain of the point he wanted to make. Annie’s eyes were glued to his face. Speaking haltingly, he ended the discourse. “Anyone can talk to God, Annie, anytime and anywhere. That’s prayer, Annie. God wants us to talk to ‘Im. ‘E loves to ‘ear us speak to ‘Im and ‘e always wants to ‘elp us fur ‘e loves us. And you can’t ‘elp prayin’ if ‘e loves you.”

Looking at his daughter rather helplessly, John Spence wanted to say more, wanted to impart the change he felt had come over his heart. It was a long speech he had made, and he wasn’t at all sure he had told Annie these things properly – things that were becoming more and more important to him every passing day. But he comforted himself with the thought that he would tell her more as time went on, and that he would soon be able to take her to the meetings.

“Aren’t you lookin’ fur work no more Da?” Annie’s voice was perplexed. She had not understood what he had just said.

“Annie, at the meetin’ I met this man. ‘Is name is Will Marley. ‘E’s thinkin’ that a gardener, ‘andyman of sorts, is needed at this place ‘e knows. “E’ll tell me tomorrow.”

He smiled at her and Annie was sorely tempted to tell him that she had a job too. But the thought of the surprise come Sunday, when she would lay her wages in Da’s hands, was even more tempting.

“I’m so glad, Da,” she whispered, “I knew you would get a job.”

“I got summat fur you, Annie.” John pulled out a small book. “I got this from Will. I was shamed to tell ‘im I couldn’t read. But you kin read – leastways a little bit.”

“I got summat fur you, Annie.” John pulled out a small book. “I got this from Will. I was shamed to tell ‘im I couldn’t read. But you kin read – leastways a little bit.”

Annie took the book and looked at it curiously. Turning the pages she saw verses and songs. “Why, Da, this ‘ere’s a songbook. Do you sing songs at the pub?”

“Lots of singin’ there, Annie. I’m goin’ to take you soon – as soon as the job’s settled and we’ve paid Susan.”

***

Susan came to the room to fetch her down the next morning. Mrs. Darcy, imposing in the severe, brown ulster and lace shawl, was waiting like a sentinel at the bottom of the stairs. She smiled at Annie again. It was rather a stiff smile but it still made Annie think of her Mum. Leaving Da behind wihtout a word was hard. But Susan had assured her again on the landing that it was for the best. “I’ll tell ‘im – don’t you make a fuss now! I’ll tell ‘im about what’s ‘appened, and ‘e’ll thank ‘is good fortune fur your common sense.”

“Ready, Annie?” The brown ulster moved towards the door. Annie moved too, a little uncertainly. Outside, on the feeble flight of the entry stairs, she breathed in the morning air.

Eliza was sitting at the bottom of the steps. Mrs. Darcy avoided touching her by holding her skirts to the side as she passed, walking quickly ahead. “Ello, Annie. You’re off then?”

“Yes.”

Annie was stiff in her nervousness.

“Your off with the likes of ‘er?” Eliza pointed a thumb at Mrs. Darcy who was already about twenty feet down the alley.

“Yes,” Annie whispered, “she’s goin’ to buy me sum new clothes.” Almost running to catch up with her fairy godmother, she threw one more sentence over her shoulder, “‘Ope I see you agin, Eliza.”

But Eliza began running too and tugged at Annie’s ragged skirt. “Annie!”

Annie turned. Eliza’s face was contorted – funny-like. It almost seemed as if she were going to cry. “Don’t go Annie.”

Annie smiled. “It’s nowt to bother yourself about, Eliza. I’m comin’ back to see Da on Sunday and I’ll see you too.”

Annie didn’t turn again. She visited heaven that morning. Mrs. Darcy took her to a dress shop where a lady outfitted her from head to foot: a reddish frock, a cape and a hat. The only thing that puzzled her was the fact that these did not appear to be working clothes. When she asked Mrs. Darcy about this, she did not receive a clear answer. “Mr. Darcy, he’s what you might call a little fastidious. He likes to see girls neat and trim.”

Annie didn’t know what fastidious was, but on the whole she gloried in the feel of the new material on her body. Wouldn’t Mum have been proud. And that almost brought the tears.

It was early afternoon when Mrs. Darcy hailed a cabby and holding on to Annie’s hand, stepped up into the carriage. Annie felt quite the lady in the four-wheeler. She’d ridden in a neighbor’s cart before, and that on bumpy country lanes. The sky had been the canopy and the trees and the grass had waved. And Mum and Da had laughed. There were those tears again. She felt the new frock’s warmth and fingered the material for comfort.

“Where are we ‘eadin’ now, Mrs. Darcy?”

Mrs. Darcy hadn’t said much all morning. Annie had caught blue eyes staring at herself several times with a most peculiar expression. It frightened her. She had expected to be in a kitchen by this time, perhaps scrubbing pans or dusting shelves or sweeping some steps. “Mrs. Darcy, please, where are we ‘eadin’ fur now?”

Mrs. Darcy’s eyes slowly focused on the girl. “To another lady, Annie – a friend of mine. She’s a doctor of sorts. She’s going to give you an examination.”

The word examination scared Annie terribly. She shifted away into the cabby’s corner unconsciously eyeing the door. Mrs. Darcy went on.

“You see, when you work for people that, well, that are a little more well-to-do, you have to be healthy. So she’ll check you over. Make sure that you’re not sick.”

She paused and her voice rose a little as she continued. “So, you’re to do what she tells you. Do you understand, Annie?”

Annie nodded. She was confused and not at all happy anymore.

“Number 36 Millwood.” The driver opened the cab door and they alighted. Annie felt her hand being taken again, firmly, and the hint of unease which had overtaken her in the cabby turned her stomach sour.

“Is this where your friend lives, Mrs. Darcy?”

“Yes, Annie. And please remember what I told you. Do everything she tells you.”

***

It was dark and dank in the room. Heavy drapes hung on the windows. In spite of her new clothes, Annie shivered.

“Annie, this is Mrs. Broughton, the lady who will examine you.”

Annie regarded a heavy woman whose wheezing breath came quickly. She had no smile, but only pointed to a screened-off partition in the far corner of the room. Annie rigidly moved towards it feeling awkward. There was a bed behind the partition.

The examination lasted less than five minutes. As Annie re-arranged her clothes, she did not hear Mrs. Broughton’s low aside to Mrs. Darcy.

“You got your money’s worth. She’s a virgin.” In a louder voice the woman carried on, “That’ll be twenty shillings, if you please.”

Mrs. Darcy paid. Annie would not look at Mrs. Brougton as she unsteadily made her way towards the door. In the hall she somberly stated: “Your friend is a dirty, fat woman and I wouldn’t ‘ave come if I ‘ad known what she was goin’ to do. I don’t think my Da would like it either.”

Mrs. Darcy took her hand. “Now, Annie – an examination is never pleasant. But it’s over now and we’ll go for another ride in a cab. You like that, don’t you?”

Annie didn’t answer. And the new frock began to feel hot and heavy.

Outside she shakily took in great gulps of air. The cabby was still there, waiting. In the shadows of the bushes by the side of the road, Annie thought she saw the form of a girl. It very much minded her of Eliza. She peered and would have walked that way, but Mrs. Darcy’s hand imprisoned her own, pulling her strongly towards the cabby. “Come on, Annie. Don’t dawdle!”

The cabby drove briskly through the warmth of the summer afternoon. Loud cries of vendors selling their wares stridently grated past them. Annie could see calico blinds on the windows of the many tenements they passed. Some windowsills held penny flower bunches in cracked vases. These were all homes and belonged to different families that had Mums and other children.

“Ave we long to go?”

Mrs. Darcy turned her shawl-wrapped face towards Annie. “We’re almost there, Annie.”

There was something in her eyes which made Annie refrain from asking any more questions.

***

There was a garden. Annie could see it straightway when the cabby stopped, and in spite of the high walls which surrounded the house, and in spite of her growing discomfort, this garden made her glad. She had been born and bred outside the city and the sight of green was like an old friend waiting.

But the dwelling itself was foreboding and scowlingly large in dimension. Indeed, it seemed quite too large for just two people like Mrs. Darcy and her husband to occupy by themselves. The cab-driver opened the carriage door and, after stepping down, Mrs. Darcy paid the man.

“Do you live ‘ere alone?”

Annie’s timid inquiry brought a strange smile to Mrs. Darcy’s face. She did not answer Annie’s question, but took her by the hand again, through the gate, up a stone walk to a big front door. There was no one behind the door. Somehow, taking into account the size of the immense house confronting her, Annie had expected several people behind the door – people like butlers, maids and housekeepers. But there was no one. Immediately behind the door was a steep, thin stairway. And the whole area smelled faintly of gas mixed with something sweet, minding her of dying flowers.

Mrs. Darcy pushed Annie towards the stairs. “Up you go, Annie. I’ll show you to your room.”

“You mean I’m to ‘ave a room?” The child was overcome with amazement. Where she came from entire families lived in rooms, not single Annie Spences.

Behind her Mrs. Darcy grinned. She slapped Annie’s small behind playfully. “Yes, you get your very own room.”

The stairs led to a long, narrow hallway with many doors. The hallway was not empty. Several girls, all in silk dresses, stared at Annie. Some eyed her with curiosity, some with apathy and some with pity. Annie felt uncomfortable. Did they all work here? She suddenly wanted to leave and abruptly turned, only to find Mrs. Darcy right behind her – Mrs. Darcy, suddenly a wall, like the wall around the garden.

“I’ll show you your room, Annie.” It was not an invitation but a command.

She walked on even as one of the girls tittered. Then several laughed out loud. One bowed to another, saying in a falsetto voice, “Your room, your majesty – your very own room.”

Determined, Annie turned around once more encountering the cold eyes of Mrs. Darcy. She swallowed audibly before speaking. “Mrs. Darcy, you can ‘ave your clothes back. No disrespeck intended but I’d rather talk to Da furst.”

But even as her mind formulated the words and her mouth said them she knew inside herself with a deep, desperate fear, that there was no going back – perhaps not ever. There was no response. There was only a firm push towards the first door in the hallway on the right.

The room behind the hallway door held a bed, a dresser and a chair. Staining that bed was a red, silk dress. Mrs. Darcy closed the door behind them and moved towards the bed. Taking off her gloves slowly, she sat down heavily on its edge. The dress lay next to her.

“I want you to listen to me very carefully, Annie Spence.

Annie stood with her back against the wall and saw that Mrs. Darcy’s penetrating eyes had turned an icy-blue. They were totally devoid of the smile which had initially won Annie’s confidence the day before.

“You’re a big girl now and you can’t go back to your Da. I want you to put on this pretty, red dress and in a little while I’ll bring you up a bite to eat. This evening a gentleman friend will come up to visit you.”

A horrible realization came over Annie. She was only twelve, but through the years she had seen her mother bear child after child.

“I want nowt to do with no gentleman,” she whispered hoarsely.

Mrs. Darcy just regarded her. Annie’s hands nervously twisted together and she footslogged over to the chair. The dress appeared as repulsive to her as Mrs. Darcy. Her thin hands unclasped and clutched the arm of the wooden chair. And a great anger overcame her: anger at the lies she had been told, anger at her own foolishness for believing them, and anger at Mrs. Darcy for telling them. Before she knew it, she had lifted the chair above her head and had heaved it with all her might at the woman sitting on the bed.

But Mrs. Darcy ducked and came at her, pulling a white kerchief from her pocket as she did so. Managing to grab Annie’s arm and snatching her close, she pushed the kerchief against Annie’s face. There was a sickly-sweet odor. It nauseated the girl. Slowly losing consciousness, she was oblivious to the fact that Mrs. Darcy summoned another girl from the hall into the room. She was also entirely unaware that between the two of them they undressed her, slipping her childish, inert body into the red dress.

“She might be a touch one,” Mrs. Darcy declared thoughtfully, “Maybe I can frighten her with… well, I’ll see… a little hunger and loneliness won’t hurt. We’ll give it some time.

***

John came home fairly early that evening, his step more buoyant than it had been for the last few days. Will had said after the meeting today that he could bring his Annie over tonight and that the job was sure.

“Ere, man,” he’d said, “’ere’s sum munny to get that Jarrett woman off your back.”

When John had stared at him in a somewhat bewildered way, he had added, “A room cums with the job, John. Yourself and your Annie can share it – and I’m certain the Morrows will ‘ave sum work about the ‘ouse fur Annie too.”

The meetings were becoming less and less foreign to John. Tonight he had watched a newly-converted man roll a beer barrel from his house and tip its contents down the gutter. He’d also seen others, risking ridicule, confess their sins up at the front, kneeling down at what was called the “Penitent form.”

Perhaps all these things wouldn’t have made such an impression on him but that Will Marley had been such a friend. Every day asking him how was he doing and how was Annie? Every day sharing his bread, and what he had wasn’t much. Every day promising to look out for work. Will was a chairmender. He rolled his barrow through the streets of London crying “chairs to mend – chairs to mend.”

He’d given John a detailed account of how he’d been a chimney sweep as a lad of six. “Me Da, ‘e died of the cholera when I was a tad. Mum needed the munny. The advertisement asked for small boys to fit narrow flues. I was small all right. Only got one meal a day. ‘Ad to start work at four every mornin’. The master sweep would put a calico mask over me face and a scraper in me ‘ands. Then ‘e’d push me up the chimney where I’d ‘ave to loosen soot fur ‘im. If I fell, and I did that, the sweep would put me ‘ands in a salt solution to ‘eal and ‘arden them. Oh, John, the sting of it! I can still feel it. Then I began to drink. Me poor Mum saw little of the munny I earned. Then I quit the sweepin’ and started snatchin’ dogs from people, wealthy people mind you, and sellin’ them. Then I saw a man ‘ang outside Warwick gaol. And it came to me that that man could be me. Then I ‘eard this fellow, Elijah Cadman, speak. ‘E used to be a fighter – a regular boxer like – and ‘e spoke about ‘eaven and ‘ell as if they were over in the next alley. Anyway, I got the call. God moved me, you might say, and I got into a straight business, chair mendin’, and ‘ere I am.”

John didn’t quite understand the rationale behind all of Will’s story. But he did understand that Will was helping him, was feeding him, and would put Annie and himself up for the night.

He’d reached Susan Jarrett’s place. It would be the last time that he’d run up these rotten stairs.

“Annie’s Da?” A small voice called to him from below. There was a girl with red hair and she looked to be about Annie’s age. It came to him that Annie had spoken of a friend last night. Maybe this was the girl. He smiled.

“You know me Annie?”

“Well, she’s not ‘ere any more. She was taken away.” The girl’s voice was breathless, shaking a bit in the telling.

John walked down the stairs again, towards her. “Wot’s your name, child?”

“Eliza.” She faced him candidly, blinking at the fierceness of his rising voice but not backing away from it.

“Wot do you mean, Eliza, by wot you just said?”

“I mean that Annie, your girl, she’s gone. Left fur a job. She told me yesterday that she ‘ad a job. So I came out this mornin’ to say goodbye and she left with this woman and, and…” Eliza stopped, swallowed and then haltingly continued. “The woman, the woman – well, she was bad.”

“Bad?” John’s knuckles showed white as she gripped the edge of the splintered railing, leaning closer towards the girl.

“She was no good. I know when someone’s no good. She ‘ad this walk. I tried to tell Annie, but this woman told ‘er to come.”

“Why would Annie leave without tellin’ me? She always tells me wot she’s about. Wait ‘ere, Eliza.” John turned and ran up the steps to the Jarretts’ room.

Susan met him in the hall. “‘Ome are you, John?”

“Susan, where’s Annie?”

“Annie? Why, in your room, I suppose.”

“‘Ave you looked?”

She stared him straight in the eye, lifting her eyebrows in a perplexed way, and John was puzzled. Was Annie there after all and was the girl outside leading him on? He ran past Susan up the steps, three at a time, to the second floor. The wood creaked and moaned under his weight. The flimsy door opened and stayed where he flung it against the wall. There was not even a hint of Annie in the room. There was only the bareness of the place. The cracks in the wall – the small, dingy window – the lingering odor of death – but no Annie. He turned and walked back, walked slowly this time, thinking. Susan was still in the hall.

“Did you find Annie then?”

“No.” His answer was short and terse.

“Where do you suppose the girl would go?” Susan’s voice was sympathetic and once more he wondered. She had, after all, let them stay here and they owed her.

“Eliza says a woman came and took ‘er away today.”

“A woman?”

“Yes.”

“Didn’t see no woman come ‘ere. But I told Annie she could sit on the steps. Maybe sum woman come by. I wouldn’t rightly know.”

John changed the subject. “Got your rent, Susan, and maybe sum besides.”

Her eyes never left his face. “That so, John. Well, I reckon it’s about time.” Her expression didn’t change, but her heart thought of the two pounds Mrs. Darcy had given her and how it was hidden away in the torn part of the chair in her room. John counted out the money into her palm and walked away.

“If you ‘ear,” he said and she nodded again smiling all the while, but condemning him for a fool in her heart.

Eliza was still standing where John had left her. He sat down on the bottom step, his eyes on her face. In a cracked voice he mumbled, “She’s gone. You spoke true.”

“I know.” Eliza’s tone was soft and she stood by him quietly.

“I got me a job today. A decent job and I took the pledge too. I’m not goin’ to drink any more.”

The girl sat down next to him. “Annie’s da,” she divulged slowly, “I know wherabouts she is.”

Incredulously he lifted his head and turned to face her. “You know where me Annie is?”

She nodded and continued, “I follered ‘er and that lady today. She got sum new clothes and then I ‘ad to run quite ‘ard to foller because they took a cabby, but I know the street and the ‘ouse they stopped at. And then they got back in the cabby again and I follered again to another ‘ouse. It’s a big place she’s at.”

John gaped at her. “Will you take me there, Eliza?”

“Can’t now, Annie’s Da. Me Mum’s always in a dreadful ‘uff if I ain’t ‘ome in time at night. But tomorrow I’ll take you.”

“Thank you, Eliza.” There was a faint glimmer of hope in his eyes. “First think in the mornin’?”

“I’ll be ‘ere, waitin’ fur you, Annie’s Da.”

There was not a shadow of a doubt in John’s mind as he walked out of the alley, that he could trust Eliza. There was that about her, just as there was not that about Susan Jarrett. He’d go to Will’s place now. There’d be a corner for him there. He knew there would be.

***

Annie woke uneasily in the bed. The ceiling overhead leered at her. Pink it was, and the plaster was peeling dreadfully. Her head was sore and her mouth felt dry. She ran her tongue over her lips.

“Awake then, are you?” Mrs. Darcy’s voice brought it all back to Annie. She raised her head painfully, suddenly aware that she was wearing the scarlet dress. It was unpleasant to her touch and she shrank from herself. Mrs. Darcy stood up.

“I hope that you’ve calmed down a bit, Annie. I stayed with you just to make sure you’re all right.”

Annie studied her distrustfully.

“I want nowt to do with you. I want to go to me Da.”

“Your Da’s a poor man, Annie. He’s not got enough to feed you properly. Besides, he won’t want you back once you’re spent time here.”

“Me Da always wants me.” Annie’s voice rose in defense.

“Do you know where you are, Annie?”

“I’m, I’m….” She stopped, confused.

“You’re in a brothel, Annie, in a house of ill repute, a house where bad girls stay. Do you understand, Annie? Once you’ve stayed here, everyone will think that you’re bad. No one will want you anymore.”

“Me Da will, ‘e ….”

“Your Da thinks you’re lost and after a few days he won’t bother looking any more. He’ll think you’ve drowned in the Thames or some other river. He’ll give up looking for you, Annie. Do you understand?”

Annie put her head down, turning her body away from Mrs. Darcy. She hated the woman with her whole being.

“Annie, if you don’t do what I say, the same thing will happen to you that happens to other girls who don’t do what I say. You will be doped, put to sleep, and put into a coffin. I have coffins downstairs, Annie. The lid will be nailed down right on top of you. Then you will be shipped to another country where you might not know the language and you will never come back here. I would sell you as a slave, Annie.”

Mrs. Darcy’s voice dropped. “Imagine that trip in a coffin, Annie. Close walls suffocating you and you not able to move, maybe not for days. And you’ll claw at the wood around you and scream. But,” and she paused dramatically, her voice dropping another decibel, “no one will hear you and no one will care!”

Annie listened in horror. Clenching her thin fists, she buried her face in the bedspread.

“I see that you’re thinking things over.” Mrs. Darcy’s voice was smooth as the silk on Annie’s dress and twice as repulsive. “I’ll be back in the morning and we’ll talk some more.”

As soon as the door clicked into its lock behind Mrs. Darcy, Annie was off the bed. She padded over to the window and peered down into the dusky garden. How glad she had been to see it initially. It so made her think of the country. She pulled at the latch to open the window but it stayed fast. She turned, surveying the room, her very own room, and grimaced. Bending low she peeked under the bed. There was nothing there, barring the dust. The clothes that Mrs. Darcy had bought for her that morning were gone. The chair held nothing. She stepped towards it and the silken dress rustled as she went. But then her right foot struck something. It was the songbook Da had given her, lying by the chair on the floor. It must have fallen out of her pocket as they undressed her. She picked the little volume up, cradling it in her hands. Da had carried it and it was like touching him for a moment.

Weakly Annie walked over to the chair and sat down, all the while clutching the small tome. Da had really wanted her to have it. He had changed since they’d come to London. It wasn’t just the grief he felt over Mum. No, he was changed in a different way. And somehow, it had to do with this book. She caressed it with her hand, feeling its cover, feeling Da’s rough hand holding her own. Then she opened it. There was something written on the flyleaf. She spelled out the words slowly: I call on you, O God, for You will answer me.

What strange words! What exactly had it been that Da had said to her about these meetings anyway? There had been something about talking to God. But what was she sitting here for, thinking about these things, when she should be figuring out how to get away. It was dark already. Would Da be home now and coming into their room? And what would he think with her gone? Susan Jarrett would tell him that she had a job – or would she tell him something else? That part was muddled in her mind. Da would likely miss her and come searching for her. Wouldn’t he?

Annie got up and walked back to the window again. Her hands explored the latch carefully. She pulled and poked. Her nails scraped around the edges to possibly loosen things a bit. But nothing moved – nothing gave way. There was not even a hint of a creak to suggest that perhaps in time the window might open. She turned and went over to the door. Gingerly her hands touched the handle. It came down a little, but then stopped. The lock was secure. She bent to peer through the keyhole, but there was only darkness. Then hopelessness gripped Annie so that her whole being became ill with fear. She threw herself onto the bed and wept and wept. And no one came to comfort her.

Annie finally fell asleep. It had been a long day and she was exhausted. But her sleep was fitful and she continually whimpered in her dreams. She saw Da walking away from her, his form exuding disappointment. She saw Mum, tired and heavy, walking the road to London. Mum wouldn’t raise her eyes to Annie’s face, wouldn’t give her even a bit of a smile. She felt the weight of the dead infant in her arms again and then Susan Jarrett shoved her about with a broom, shouting all the while, “You’re a wicked girl – a most wicked girl.”

***

It was almost dawn when Annie opened her eyes. She turned her head slowly, fearing to see Mrs. Darcy back on the chair guarding her. But there was no one. Her hands felt cold and cramped and, looking down at them, she discovered that she was still clasping the songbook. She had done so all night.

“Anyone can talk to God, anytime and anywhere. That’s prayer, Annie. God wants us to talk to ‘Im. ‘E loves to ‘ear us speak to ‘Im and ‘e always wants to ‘elp us, for ‘e loves us. And you can’t ‘elp prayin’ if ‘e loves you.” It was as if her Da was in the room with her. The words resounded in her mind. And a great desire was born in her to speak with Da’s God.

“Wot will I say, Da?” she whispered, “Wot will I say? Can I say wotever I’ve a mind to say. Can I ask ‘Im anything?”

Sitting up in the bed, she shivered and turned her head towards the closed window. Then, swinging her feet over the edge, she cautiously began to speak. “Ello, God. Me name’s Annie Spence. I’m locked up in this room and this is a bad place to be in.”

She stopped and sobbed. Saying the way things were sounded harsh and she was afraid of this morning. Then she stopped crying and went on.

“Me Da, ‘e told me this was prayin’ – leastways I think that’s wot ‘e meant. So if I’m not doin’ it right, I’m sorry. I’m so scared, God, of Mrs. Darcy and I shouldn’t ‘ave gone with ‘er without tellin’ Da. Maybe I’ll never see ‘im again.”

She stopped to blow her nose into the bed covering. “I don’t know wot to do, God. And I don’t know ‘ow to end talkin’ to You neither. Maybe I can talk to You agin sometime.”

She stopped to blow her nose into the bed covering. “I don’t know wot to do, God. And I don’t know ‘ow to end talkin’ to You neither. Maybe I can talk to You agin sometime.”

A bird sang faintly outside. Annie got up, stretched her arms and legs and plodded over to the window. She put her hand up to the pane, hoping to maybe catch a glimpse of feathers. Lightly her left hand rested on the pane as she peered, and noiselessly the window slid open towards the outside. The small book felt warm and alive in her right hand. The bird sang again – louder this time. Annie smiled. “I love You, God. Can You ‘elp me jump down too, please?”

The distance down below to the garden was frightening. Annie swallowed audibly, her eyes widening at the drop. It was high – a good twenty feet at least. She turned and brought the chair over to the window. Climbing onto it, she was able to scoot onto the sill, advancing her feet precariously over the outside edge. There were voices in the hall. Annie shut her eyes and felt herself drop. Then everything went black.

***

“Annie! Annie! Wake up. Annie, please, we ain’t got much time.”

Annie moaned. Her eyes opened half-way. A face swam into focus – a friend’s face. She knew who it was but could not think of the name.

“Annie! It’s me, Eliza.” The voice carried great urgency.

“Eliza?” The name crept around in Annie’s mind. She didn’t understand what had just happened.

“That was some jump, Annie. I shut my eyes when I saw wot you ‘ad in mind to do. But it’s time to get up now. We’ve got to get goin’. Your Da’s so worried.”

Annie mind cleared a bit. “Da? Is me Da ‘ere?”

“Your Da’s comin’ fur you this mornin’, but not if you don’t get up.” Exasperated Eliza pulled at Annie’s arms. “Ere, I’ll ‘elp you.”

Annie half-sat up, still unsure of what to do. Eliza supported her under her armpits when she tried to stand. “Me leg! I’ve ‘urt me leg, Eliza!” Annie almost sat down again.

“If you don’t walk soon, sore leg and all, they’ll nab you and put you back in, Annie. Please try to walk! ‘Ere, put your arm about my neck then.”

Annie did, but she almost gagged when she took the first few steps. “Eliza, ‘ave we got far to go?”

“Soon’s we’re out of sight of the ‘ouse, Annie, we’ll find a place to rest. But we got to move quickly, see, or they’ll be after us.”

They moved through the garden – Annie hobbling and leaning heavily on Eliza. The gate was open and the street lay before them. Early vendors trudged about. A flower girl, bare, dirty feet showing under an equally dirty, tattered skirt was setting up a stall. A few women, clad only in soiled petticoats, were on their way to factories. Pitiless morning light showed their faces dull and devoid of emotion. They simply walked. The hot-baked-potato man was doling out breakfast to a group of sweeps.

“Ey there!” one of them called out as Eliza and Annie passed, ‘Aint you out a bit early fur business!” They all guffawed and Eliza’s arm about Annie tightened protectively.

“Eliza, your a good friend. And I only just met you yesterday. I’m so glad you ‘elped me.”

Eliza shrugged.

“I ‘ad nothin’ better to do anyway.”

“Wot did me Da think, Eliza, when ‘e found out I warn’t ‘ome?”

“‘E went in and talked to Susan and she told ‘im that she didn’t know where you were. That you were sittin’ on the porch and most likely wandered off.”

“But she told me she’d tell Da I was workin’.” Annie stopped walking. Indignation blazed out of her eyes. “She told me…”

Her voice trailed off. Eliza prodded her with her shoulder to keep on walking.

“She got paid, Annie. This woman you went with….”

“You mean Mrs. Darcy?”

“Whatever ‘er name was. She pays people. She pays nursemaids, charwomen and others like Susan Jarrett, to tell ‘er about lost, young girls that might be good prospects for ‘er ‘ouse like. Me sister, she was spoken to by this lady dressed up as a nun. Real sweet-faced lady she was. But she warn’t no nun. And she doped up Maude, that’s me sister, and when she come to there was this man in a room with ‘er….”

Annie gasped. “Wot ‘appened, Eliza?”

“You don’t know our Maude, Annie. She made like she was crazy. Foamed at the mouth. Tore at ‘er ‘air. The man thought she’d escaped from an asylum and ‘e left. They let ‘er go after that.”

Annie sighed. “I threw a chair at Mrs. Darcy, but it didn’t ‘elp much. Can we sit a minnut, Eliza?” Annie’s leg throbbed more at every step. Eliza anxiously looked over her shoulder.

“I suppose we’d ‘ave known by now, ‘ad they come after you. Sit then, but only fur a minnut or so.”

Gratefully Annie sank down at the side of the road. The red dress was ripped and soiled. She felt unclean in it. “Me clothes are gone, Eliza.”

“Not to be ‘elped.”

“‘Ow did you know where I was?”

“I follered you yesterday. You sure traveled! I was about wore out with follerin’. I told your Da I’d take ‘im over as soon as it was light, but I couldn’t sleep last night, worryin’ they might take you somewheres else. So I spent part of the night in the bushes in the garden. Lucky I woke to see you swingin’ your legs over the edge of the winder. Lucky too, you didn’t break your neck.”

Annie squeezed Eliza’s hand and got back up.

***

It took them two hours to reach Eliza’s place. Annie’s wrenched ankle was swollen out of proportion by this time and Eliza was half carrying her. It was the same alley that Susan Jarrett lived in. The room Eliza shared with her family wasn’t much better than the one Annie had shared with her Da. There were two straw mattresses in a corner on the floor and the small wooden table held a cup with a small bunch of mignonette. The greenish-white flowers welcomed Annie as she gratefully sank onto the straw.

“I’ll go and look for your Da now, Annie. Why don’t you sleep a bit?”

Annie didn’t even hear the admonition. She was already asleep, sore leg stretched out in front of her.

***

John Spence was sitting on the bottom steps of Susan Jarrett’s stairs, head leaning heavily on his hands. He did not hear Eliza coming and startled to hear the sound of her voice.

“Annie’s Da!”

He jumped to his feet directly. “I’m ready to go when you are, Eliza.”

“No need, Annie’s Da. She’s at my place, sleepin’.”

John stomach lurched. “She’s all right then? Me Annie, she’s all right?”

“Well, she’s ‘urt ‘er foot a mite. But fur the rest I think she’ll do fine.”

“Where do you live, Eliza?”

Eliza glanced up at the stairs. In the morning dawn, she thought she detected a shadow figure on the landing. Motioning John to follow her, she told him all that had happened in the small hours of the day, but only after they had put some space between themselves and Susan Jarrett’s house.

***

Annie was sleeping soundly. The red, besmirched dress covered her childish form poorly. John knelt down on the floor and touched her arm. She opened her eyes slowly and made as if she were about to cry. “Da! Oh, Da! I’ve lost the book!”

Annie was sleeping soundly. The red, besmirched dress covered her childish form poorly. John knelt down on the floor and touched her arm. She opened her eyes slowly and made as if she were about to cry. “Da! Oh, Da! I’ve lost the book!”

He gently stroked her hair. “Wot book, Annie?”

“The one you gave me, Da. I lost it when I jumped and now it’s gone.”

“Never mind, Annie! Never mind!” John had never been one for hugging. He’d never been able to say much about love. But now words tumbled from his mouth as if they had always been there. And maybe they had. “Annie, girl, when I come ‘ome and you were gone I cried… and I prayed….”

Annie touched his hands. “I know, Da. I know. I understand wot you meant about prayer, Da.” Her eyes were shining, full of understanding. “‘E opened the winder fur me, Da. And now we can begin agin.”

Mrs. Darcy, bird, and songbook pictures are by Charity Bylsma. Christine Farenhorst has a new book out, “Listen! Six men you should know,” with biographies on an intriguing selection of famous figures: Norman Rockwell, Sigmund Freud, Samuel Morse, Rembrandt, Albert Schweitzer, and Martin Luther King Jr. You can find it via online retailers including Dortstore.com.