Your wife discovers some flowers in the kitchen and thanks you with a hug and a big kiss for “such a thoughtful surprise!” You bought the flowers for your secretary in honor of “Secretaries Day” at the office. You can either take the credit for thoughtfully buying your wife flowers or you can tell your wife that they weren’t intended for her.

Do you tell her the truth, yes or no?

***

This question was part of very odd but interesting game. To win it you had to successfully predict what your friends would do in different moral dilemmas. Almost everyone in the room (both the men and women) thought that in this case a little white lie would be the best idea.

But the question was directed at Glenn and he thought differently. Lying to his wife wasn’t an option to him; this was his most important earthly relationship so marring it with dishonesty seemed silly to him. Yes, when he told her the truth his wife wouldn’t be as happy with him at that moment. However, if she knew she could count on him to always be honest, even in the small things, then she would know she could count on him in the big things too. And wouldn’t that benefit his marriage far more than a little extra undeserved credit he might get from saying the flowers were for her?

A more realistic test

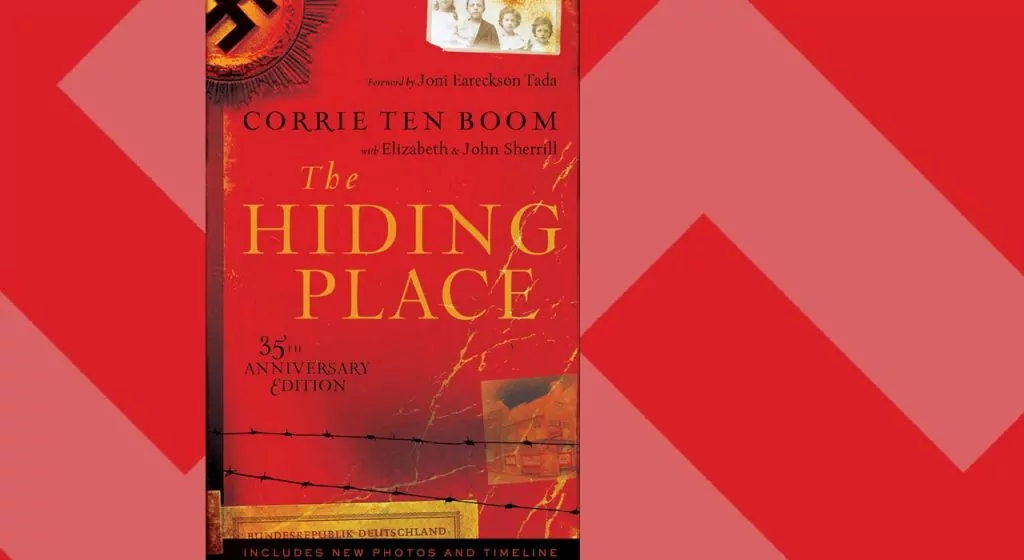

When Christians debate the issue of lying it’s most often in the context of whether we should always tell the truth – should we, for example, tell the truth if Nazis come to the door and ask us if we are hiding Jews?

But in her book Anatomy of a Lie, Diane Komp notes that very few Christians are confronted with this sort of extreme situations – few of us are ever faced with a circumstance in which telling the truth might put someone else’s life in jeopardy.

Instead, she notes, we lie for a far more trivial reason: because it just seems easier.

Telephone solicitors get the “we can’t talk right now” response whether we can or not; the waitress asking “How are you?” is given a “good” whether we are or not; children who want to play with Mom or Dad are told “later” whether there will be time then or not. We lie because it seems the quicker thing to do, because the “half-truths” we’re telling seem harmless enough, and because we doubt the sincerity of the people around us (“He can’t really want to know how I’m doing, can he?”). Eventually, we’re lying simply because we’ve gotten into the habit. Then we do it so often we don’t even notice ourselves at it anymore.

The scariest part of Komp’s book was the chapter in which she suggested the reader, over the space of a few days or weeks, record “every time you lie, or are tempted to, and ask yourself the question ‘why?’” Try this and I think you’ll be startled by how often you “stretch” the truth for no reason at all, without even thinking.

Of course, not all lies are motivated simply by habit. We also lie to protect ourselves, to either cover up something we’ve done or failed to do. Would the husband at the beginning of this article feel any temptation to lie if he regularly remembered to get his wife flowers? Of course not; then it would be only a minor thing to tell his spouse that this time these flowers were for someone else. But because he’s neglected his wife for so long there is now a temptation in these circumstances to take credit for thoughtfulness the husband hasn’t had for his wife for quite some time.

Harmless?

So the more important issue is not whether it is right to lie to Nazis at the door – that’s not the issue for us – but rather whether it’s right to “stretch the truth” again and again.

The Bible is, of course, quite clear about the need for honesty and the value of truth in our day-to-day lives (Col 3:9, Lev. 19:11-12). We find that the very character of God prevents Him from lying (Num 23:19) and indeed Christ is so inseparable from honesty He is called “the truth” (John 14:6). So if we want to imitate Him then we too should be concerned about honesty.

Still, there is a temptation to dismiss the “little lies” we tell as harmless.

So let’s consider some everyday examples: how many parents make a habit out of lying to their kids, making promises they can’t keep and making threats they don’t carry out? When a parent’s “no” doesn’t really mean “no” how can they be surprised when their children don’t accept that as the final word? Experience has taught these kids that Mom and Dad’s “no’s” are at best half-truths, because half the time a bit more badgering will result in a favorable “yes.”

And how many wives can expect an honest answer from their husband when they want his opinion on a new dress. It’s become almost a game for some, ferreting out the truth. In some cases, experience has taught the wife that when she wants an honest answer from her husband it’s best to look at his eyes rather than rely on the words that come from his mouth. She has to look to his body language for an honest reaction because she can’t count on it verbally. So when he tells her she looks beautiful she’s never quite sure if that’s what he really thinks because that’s what he says all the time. This husband will find it hard to offer his wife any encouragement because even his genuine efforts will be met with skepticism.

These are just the effects that are most evident. In some circumstances we may not be able to deduce the harm caused by a bit of deception – who gets hurt when we lie to a telephone solicitor? – but perhaps the harm comes simply from the fact that if we are not habitually honest we all too easily become habitually deceptive. And sin, even small sins, separate us from God (and would do so permanently but for the grace of God) so we should never dismiss any sin as inconsequential.

The first step to a more honest life is to start off by keeping track of your deceptive impulses. Give it a try and do as Komp suggests, even if only for a day: record every time you lie, or are tempted to lie, and ask yourself “why?” Then, when you become more aware of your sin, and the misery you may be causing, you can go to God in prayer and ask him for forgiveness, more aware than before about your desperate need for it.

And then, after that, maybe you can think of your wife and go buy her some flowers!

A version of this article appeared in the May 2005 issue.