Tragedy, resistance, and change: Glimpses into the Lejac Residential School near Fraser Lake, BC

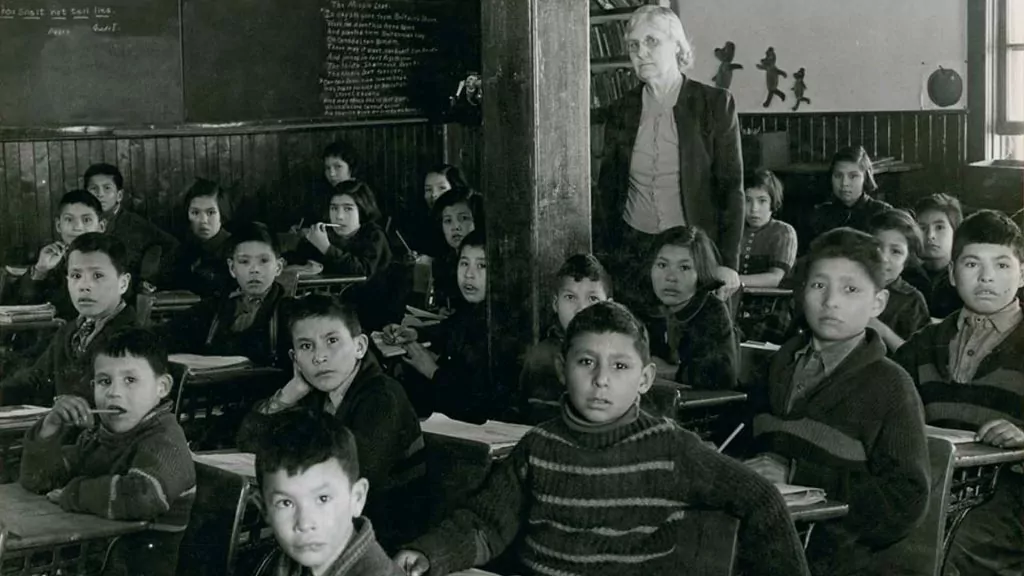

The following is based on numerous original letters, reports and other primary source correspondence that is available online. It attempts to provide some insights and context into a 10-year period (1937-1947) in one of the many residential schools set up by the Canadian government to assimilate and educate Indigenous children.

Frigid escape to freedom

The five boys walked steadily along the tracks, heading east toward freedom. They no longer glanced over their shoulders to see if they had been spotted or were being followed. It was 5:00 PM and darkness had already descended, since it was January 1st and daylight was scarce up in north-central British Columbia.

As evening turned into night, the temperature kept dropping from an already cold -20 °C toward -30 °C. The boys had been hoping to leave earlier, but since it was a holiday at their boarding school, lunch had not been served until very late – 4:30 PM – and they had less than two hours before their absence would be noticed at supper.

Paul Alex, who was ten and the oldest, was having second thoughts about running away and trying to make it home to their village of Nautley about 12 kilometers distant. It was so cold, but if they turned around now they could still make it back to the school in time for supper and escape detection. Besides, although quite a few of his classmates had run away over the years, they were usually caught and brought back by school officials or the BC provincial police, and the punishment was very harsh, maybe even a beating in front of all their classmates.

The railway tracks were easy to walk on since there was little snow, and trains rarely came through. They followed the south edge of the large lake, and very soon the boys came to a spot where they were right near the shore of the frozen expanse. Here they stopped, and far off in the distance, diagonally across the lake, they thought they could make out the electric lights of their village about ten kilometers away.

Allen, age 9, John, age 7, and Justa and Andrew, both 8, wanted to head out onto the ice and travel home in a straight line, while Alex preferred to stay on the tracks – a longer route, but more sheltered, and one that other escapees had used successfully in the past. He knew the ice was thick, but it had about 15 centimeters of snow on it, and no protection from the wind. The other four insisted on crossing the ice.

Oh, why hadn’t Bishop Coudert let them go home when they asked him earlier this morning? It was so unfair! Some of his classmates’ families had visited the school to see their children earlier in the day, since it was a New Year’s Day holiday, and it hurt so much when they drove off in their Model T’s and wagons. The boys’ hearts ached for their families and homes, especially during the Christmas week, and they would do anything to get back there, even though it was against the rules.

The Indian Act, since 1920, said that it was mandatory for all Indigenous children aged seven or older to attend residential schools where there were no day schools. Since there were almost no day schools on the remote BC reserves, this meant that the children had to go to residential schools far away from home.1 Parents who did not send their children to the boarding schools could be arrested, and several from these villages who tried to defy this law were sent to prison.2 Alex knew how frustrated the parents were, too, and how almost all of them did not want their kids to go to the school.

The younger four made up their minds and headed onto the ice. Alex couldn’t stop them, and dared not follow… and he didn’t have the courage to go on alone down the tracks. It was just too dangerous and too cold, so he turned around and headed miserably back to the school. If he hurried, he could make it back before dinner and wouldn’t get caught or punished.

Discovery and a blundered response

Alex darted back into the school undetected, thankful for the warmth and the food but worried about his friends. Sister Noella, in charge of the dining room, noticed the boys were missing and immediately reported it to the Sister Superior, who in turn informed one of the priests. He told someone else in charge, but this man thought that the bishop had given the missing students permission when they asked to be allowed to go home earlier in the day. The principal, Father McGrath, had been gone for most of the day, and there were tensions and poor communication issues among some of the school leaders.

As a result, McGrath wasn’t told until later that night, around nine o’clock, and by then he thought the boys were already safely in Nautley… likely even gone home with relatives in the late afternoon. The postmaster of the school settlement had a motorcar and it was decided to have him drive to the village in the morning to bring the boys back.

The next morning it was still very cold and the train with the mail came late, so the driver didn’t make it to Nautley until just past noon. The chief and some of the parents said that the boys hadn’t arrived, and suggested that maybe they had gone to Stellaquo, a village on the other end of the lake around 30 kilometers away. Some of the boys had relatives and friends there.

The chauffeur drove back to the school and reported to Principal McGrath, who jumped in the car with him and drove to Stellaquo to look. Nothing. The men became very worried and drove back to Nautley. Could the villagers be hiding the boys? But it quickly became obvious that they weren’t. And while there was still a bit of light late that afternoon, search parties were sent out to find them.

Stumbling homeward in the cold

The previous evening, Allen, Andrew, Justa, and John were shuffling steadily across the large lake, angling toward their village near the mouth of the outflowing Nautley River. The cold was biting, and although they wore wool socks, their short rubber boots did little to protect their feet, and the cold seeped through their jeans. Their hands were getting numb and they couldn’t stop shivering, but they pressed resolutely on, keeping their faces pointed toward the slowly-brightening lights and home.

As the kilometers slipped by, and as they got closer, they knew they didn’t have much strength or time left. Only a kilometer to go! But their hearts fell, for as they got closer a large black patch appeared ahead of them, blocking their way. It was open water, freezing cold but ice-free because of the current of the nearby Nautley River. The lake ice was thin and treacherous along the edges, and the water was too deep to walk through.

They stood in shock, shivering uncontrollably and utterly exhausted. They knew that going around to the left and further on to the lake would mean a long detour, while going to the right would mean moving to the nearby shore but away from the village. They’d have to push through the brush to the road then follow it north over the bridge to get home. But they had no energy for this anymore, hardly any strength to call out, and even if they could the villagers were all sleeping and the river was too loud. Around midnight, they slowly turned right and staggered towards the nearby shore.

The boys are found

The next afternoon, after it was clear that the boys were not at either village, search parties were sent out. The boys’ tracks in the snow were discovered and followed by three men from Nautley. Around 5:00 PM, at dusk, they found the four small bodies frozen on the ice.

Two were huddled together, one was lying face down beside them, and the fourth was about 25 meters away. The searchers quickly returned to the village, only a kilometer distant, and the coroner and local police officer were called from nearby Fraser Lake and Vanderhoof. They arrived quickly, were led to the bodies, and carefully examined them. After verifying that the boys had died of exhaustion and freezing, they allowed them to be taken to the village. One can only imagine the shock and grief, as well as the anger and frustration, that must have been felt in the villages, as well as in the school.

Far-reaching effects

Two days later, on Monday, January 4, 1937, a jury was called together and an inquest held in the nearby village of Fraser Lake, to look into the circumstances surrounding the deaths. It lasted from 10 AM to 5 PM and heard from the key witnesses and people involved. The verdict concluded that Allen, Johnny, Justa, and Andrew died on the night of January first from exhaustion and consequent freezing. They also added the following:

that more definite action by the school authorities should have taken place

more cooperation and better communication between the parents and school administrators needed to occur

corporal punishment, if practiced, should be limited

the two disciplinarians hired by the school should be able to speak and understand English (they were French priests).3

Careful investigations and recommendations

By the next day the story appeared in many major Canadian newspapers, and some implied or stated that there were underlying circumstances that led to this tragedy: inadequate clothing, harsh discipline, and poor communication among school staff. The local Indian agent, R.H. Moore, sent off a detailed letter on January 6 to his superiors at the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa, explaining what had happened.4

About a month later, Harold W. McGill of the Department asked Major D.M. MacKay, the Indian Commissioner for BC, to investigate more fully. MacKay immediately traveled up to the school at Lejac (a challenging journey by rail and car along wintry gravel roads) and spent several days interviewing school staff, students, Indigenous families, and others who could shed light on this tragedy. His eight-page report provided a thorough account of what happened.

“I am of the opinion, from the evidence and information before me, had energetic action been taken to organize a search party when the absence of the children was first noted, the children would not have perished.”

The poor communication and confusion over authority amongst the leaders of the school was a major cause for this, and it led him “…to the conclusion that the Department should take steps to strengthen its administrative control of our Indian residential schools…”

After many interviews, the BC Commissioner also wrote:

“Father McGrath was well-liked by the school children and highly regarded by their parents. There was no evidence to show that punishment of any kind had anything whatever to do with the boys leaving the school without permission. It was simply a natural desire for freedom and to be with their parents during the holidays.”

He stated that he:

“visited a number of Indian homes and discussed the tragedy with nearly all the adult Indians I met, and although I found indications of unrest and resentment, this was mostly confined to the relatives and friends of the dead children. There was no demand among the Indians or the residents of the white communities visited for a judicial inquiry, nor do I think such an inquiry at this time would be in the best interests of the Indians.”

Indigenous resistance leads to positive changes

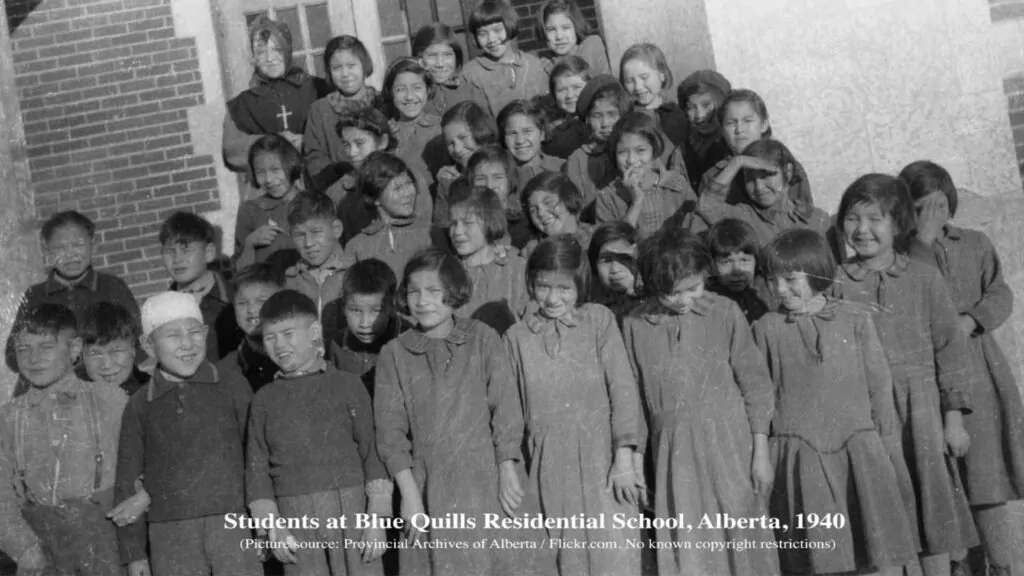

The Lejac Indian Residential School (picture credit: Library and Archives Canada, used under a CC BY 2.0 license).

However, dissatisfaction with the residential school at Lejac continued and escalated in the next several years. The principal told the inquest on January 4, 1937 that 90 percent of the parents did not want their children to attend. It’s also clear from the 1944 principal’s report, seven years later, that many local Indigenous people were strongly opposed to sending their kids to Lejac – he estimated that two-thirds were not coming to school, and that many didn’t start until age ten and only stayed for two or three years. He recommended that the law requiring all native children to attend should be enforced more rigorously.

No doubt the loss of the four boys, and the fact that so many kids ran away from the school encouraged the parents to resist even more, despite the threat of arrest. They were not opposed to education, but rather to having their children required to attend and live in an institution that was attempting to erase their culture and assimilate them into mainstream Canada. Parents lobbied instead for regular day schools to be built in their own villages, where the children could live at home and experience their own culture, similar to how most students were educated in Canada at the time.5

In September, 1945, the Member of Parliament for the region, William Irvine, met with a delegation of chiefs from the area to listen to their concerns about the Lejac residential school, and he in turn wrote to the Indian Affairs Branch in Ottawa summarizing their arguments and interceding on their behalf. The letter pointed out their issues with Lejac, namely, diseases like tuberculosis spreading easily in the crowded dorms so that healthy children would catch it, and the students spending too much time tending the fields and animals of the school to help cover the costs, which came at the expense of their education.6

In another letter, written in 1946 by the local Indian agent, the following additional reasons are provided for why 100 students did not show up when school opened (and of these, only 30 appeared when the truancy section of the Indian Act was enforced with the help of the RCMP).

“The Indians list a number of grievances, such as the time spent by students in manual labour, and religious instruction, and also, their desire for Day Schools, as reasons for keeping their children at home. The antagonism and opposition displayed by the Indians toward the Lejac residential school is more marked in recent months than at any time since I took over the agency 8 years ago.”7

The parents even hired a lawyer in Prince George to help them.

In January of 1947, the parents’ efforts began to pay off. Robert Howe, the Indian agent, wrote to the Indian Commissioner for BC, outlining the cost to upgrade a recreation hall in the village of Stoney Creek to enable it to become a school for the 66 pupils there (Andrew Paul, one of the children who’d died, was from Stoney Creek about 50 km east of the Lejac school). Howe noted in his letter that when the school opened:

“…it would be very difficult to enforce attendance at Lejac school for those who are now enrolled at Lejac. With the exception of a few orphans and underprivileged children, the parents would emphatically insist on the children attending the day school.”

He concluded his letter by stating:

“In view of the opposition and antagonism displayed by the Stoney Creek Band toward the Lejac Indian Residential School in recent years, and the extreme difficulty experienced in enforcing attendance at Lejac, I would strongly urge that authority be granted to proceed with the necessary improvements to the Recreation Hall, and that a teacher be engaged to open the Day School September 1st next.”8

The closing and legacy of the Lejac Residential School

Lejac remained open until 1976, and over its 54 years of operation, thousands of Indigenous children were forced to attend from all over northern and central BC. Things did change as time went on: more day schools were built, and by the 1960’s students from nearby reserves were bussed in to Lejac each day and no longer had to live there.

Reading excerpts from the Lejac.blogspot.com blog, and looking at the many submitted pictures suggests that there were also many happy memories from Lejac and many staff members who respected and loved the students.9 The memories and photos, though, are mostly from the last two decades of the school’s existence, when many of the earlier issues and problems had been addressed to various degrees. However, there was still a lot of misery and trauma, especially relating to being separated from the families and other community members back home.

Besides the four boys who died in 1937, 36 other students died there, almost entirely from diseases like TB, influenza, and measles – an average of about one per year despite fairly good medical care.10 One wonders how this would compare to a non-native boarding or residential school from the same era. As well, there were allegations of sexual abuse, and in 2003 a former dormitory supervisor, Edward Gerald Fitzgerald, who worked at Lejac in the 1960s and 70s, was questioned regarding numerous sexual crimes he is alleged to have committed at Lejac (and one other BC residential school); but he then moved to Ireland so he was never prosecuted (it appears that he has since died in his 90s).11 Stories of trauma came out in the recent Truth and Reconciliation hearings from former students who attended over the years, and the legacy of harm extends until today.12

In 1976 the school and most of the buildings were demolished and the land was turned over to the Nadleh (Nautley) band. The fenced cemetery is about all that remains, and some Roman Catholics still make an annual pilgrimage there to visit the grave of Rose Prince, a former student and helper at Lejac in the 1940’s and 1950’s, whom many now regard as a saint.13 This cemetery, though, is currently situated behind a huge 700-person Coastal Gaslink pipeline camp that has been set up on the property just north of Highway 16 in partnership with the Nadleh band.14

The location where the boys perished is just off the beach from Beaumont Provincial Park, located just south of the Nautley River and the village. Today, anyone who drives along Highway 16 between Fraser Lake and Fort Fraser can see the stretch of railway track and the section of Fraser Lake where the four children walked and died 86 years ago… a sad chapter of BC’s and Canada’s history.

This is one of several articles we’ve published about Canada’s history with its Indigenous peoples, with the sum of the whole being even greater than the parts. That's why we'd encourage you to read the rest, available together in the March/April 2003 issue.

End Notes

1 George V Sessional Paper No. 27 A. 1921 Dominion of Canada Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended March 31, 1920. Ottawa Thomas Mulvey Printer. See especially page 14. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?id=1920-IAAR-RAAI&op=pdf&app=indianaffairs

“The recent amendments give the department control and remove from the Indian parent the responsibility for the care and education of his child, and the best interests of the Indians are promoted and fully protected. The clauses apply to every Indian child over the age of seven and under the age of fifteen. If a day school is in effective operation, as is the case on many of the reserves in the eastern provinces, there will be no interruption of such parental sway as exists. Where a day school cannot be properly operated, the child may be assigned to the nearest available industrial or boarding school.”

2 Varcoe, Colleen and Annette Browne. Equip Healthcare. Central Interior Native Health Society. Prince George, BC: Socio-historical, geographical, political, and economic context profile. P.13. https://equiphealthcare.ca/files/2019/12/EQUIP-Report-Prince-George-Sociohistorical-Context-September-18-2014.pdf

3 Multiple original source documents can be found here: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Stuart Lake Agency – Lejac Residential School Death of Pupils 1934-1950. Pages 28-62. https://indiandayschools.org/files/RG10_881-23_PART_1.pdf Inquisition is on pp. 36-37.

4 Ibid. Jan 6, 1937 letter

5 First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC) - 1944 Principal’s report. P.90. http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IRSR10-CaseStudy3.pdf

6 FNESC – Sept. 1945 Irvine letter. pp. 91-92. http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IRSR10-CaseStudy3.pdf

7 FNESC – Sept. 1946 letter from Indian Agent R. Howe. P.94. http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IRSR10-CaseStudy3.pdf

8 FNESC – Jan. 24, 1947 letter from Indian Agent R. Howe. Pp. 95-96. http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IRSR10-CaseStudy3.pdf

9 Lejac blog (many stories and pictures from former students). http://lejac.blogspot.com/search/label/Lejac

10 National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation – Lejac (Stuart Lake) https://nctr.ca/residential-schools/british-columbia/lejac-stuart-lake/ ).

11 Fitzgerald articles: https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2003/police-lay-more-charges-in-b-c-residential-abuse-investigation/

12 See TRC website esp. videos of former students: Indian Residential School History & Dialogue Centre Collection – Lejac (lots here, including testimonies of past students): https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/entities/49

13 The Roman Catholic Diocese of Prince George. Rose Prince – Reflecting on an Extraordinary Life. https://www.pgdiocese.bc.ca/lejac/

14 Coastal Gas Link. A New Chapter for the Nadleh Whut’en and Carrier People. https://www.coastalgaslink.com/whats-new/news-stories/2020/a-new-chapter-for-the-nadleh-whuten-and-carrier-people/...