A review and discussion of Willem J. Ouweneel’s The World is Christ’s: A Critique of Two Kingdom’s Theology

****

A tour a few years back by ARPA Canada prominently featured a famous statement by Abraham Kuyper:

A tour a few years back by ARPA Canada prominently featured a famous statement by Abraham Kuyper:

“There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”

Many Christians undoubtedly agree that Christ is king over every aspect of human life. However, there is a relatively new theological movement within conservative Reformed and Presbyterian churches in North America that stands in direct opposition to Kuyper’s view.

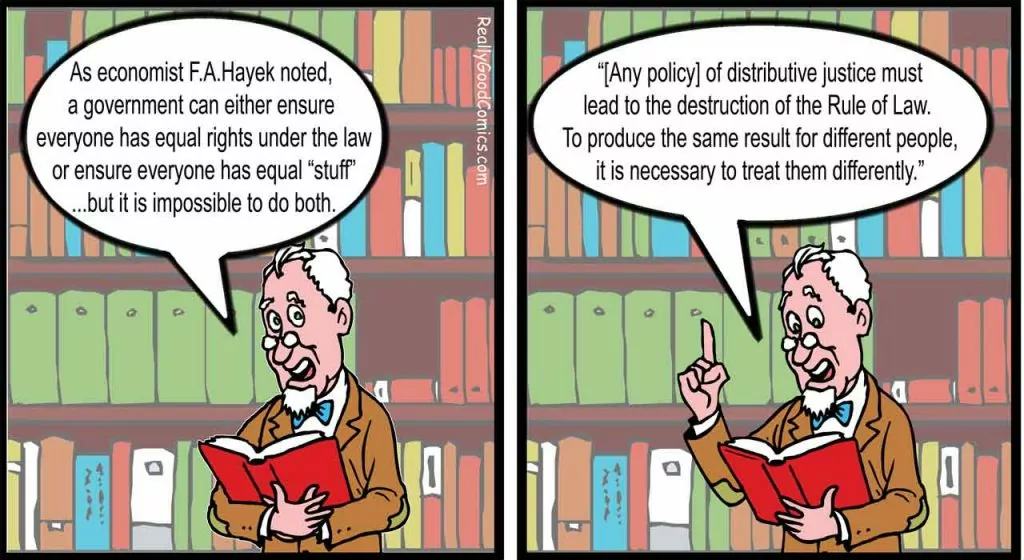

This new movement draws a sharp distinction between the kingdom of God and a secular “common kingdom” that is not directly under the rule of Christ. Hence the movement is often referred to as “Two Kingdoms” or 2K theology. Sometimes it is known by the acronym NL2K which stands for “Natural Law Two Kingdoms” theology. This is because it teaches that most institutions in society (e.g. schools, businesses, civil governments, etc.) are to be governed by “natural law” (or the law that we can deduce, not from the Bible, but from the “natural” world around us. And the reason these institutions are to be governed by natural law, rather than the Bible, is because schools, business, the civil government and more, are said to be in that secular “common kingdom.”

Two Kingdom’s growing popularity in some Reformed circles has prompted Dutch scholar Willem J. Ouweneel (who holds PhDs in Biology, Philosophy, and Theology) to write an extended analysis called The World is Christ’s: A Critique of Two Kingdoms Theology (Ezra Press, 2017). This book demonstrates that 2K is highly problematic from a confessional and biblical perspective.

New, but not so new

It is legitimate to label 2K as “new” because it has only appeared within the Reformed and Presbyterian churches in the last decade. However, there is a sense in which it can be considered to be the return of an old error. According to Ouweneel, 2K is deeply rooted in medieval scholasticism which has a dualistic perspective that divides human activities into the sacred realm and the secular realm.

For 2K, the authority of the Bible is restricted to the church and the life of individual Christians. It is not to be used as a guide for politics, economics, science, literature, etc. because those fields are part of the “common kingdom” governed by natural law.

Ouweneel’s simple summary of scholasticism also functions as a summary of the basic 2K perspective:

“there is a spiritual (sacred, Christ-ruled) domain and a natural (secular, common, neutral) domain, which have to be carefully kept apart. There is a domain under the authority of God’s Word and a domain that is supposedly governed by the God-given ‘natural law’ . . . There is a domain under the kingship of Christ and a ‘neutral’ domain (which is at best a domain that falls under God’s general providence)”

2K versus the early Reformers

However, 2K advocates claim that their view is the original Reformed position. They believe Abraham Kuyper’s “not one square inch” perspective added a new twist that conflicts with the teachings of the Reformers.

The confessions indicate otherwise. The confessions formally summarize the essential theology of the Reformers, and their statements on civil government demonstrate 2K to be in error. The original wording of the Belgic Confession on civil magistrates included this statement:

“Their office is not only to have regard unto and watch for the welfare of the civil state, but also that they protect the sacred ministry, and thus may remove and prevent all idolatry and false worship, that the kingdom of antichrist may be thus destroyed and the kingdom of Christ promoted.”

The Belgic Confession (at least in its original form) saw an active role for the civil magistrate in advancing the kingdom of God. He was not outside the authority of the Bible. Modern Christians may not agree with that statement in the Belgic Confession, but it is clearly in conflict with 2K.

The original Westminster Confession contains similar statements about the civil magistrate. For example:

“…it is his duty, to take order, that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire; that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed; all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented or reformed; and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administered, and observed.”

Ouweneel summarizes the confessional point this way: “it would have been unthinkable for the divines who wrote the Belgic Confession (Guido de Brès, d. 1567) and the Westminster Confession to accept the idea that the “secular” state falls outside the kingdom of God.” Therefore, if we use the confessions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as the standards for determining early Reformed and Presbyterian theology, 2K cannot be said to represent the original position.

2K versus Christian schools

Many Reformed Christians send their children to Christian schools because they want their children taught from a Christian perspective. Each of the subjects in such schools is rooted in a Christian approach.

However, according to Ouweneel:

“This is the very reason why many NL2K advocates object to Christian schools: they do not believe in the possibility of a Christian approach to all these disciplines. In their view, both the school and the disciplines taught there belong to the ‘common realm,’ which is neutral and secular. So why should we need Christian schools?”

If there is no distinctively Christian perspective for subjects like English, science and history, then there is no need for Christian schools. This is a consequence of the NL2K theology.

Neutral history?

Ouweneel asks, “Can you imagine studying history from a ‘neutral’ perspective?” How is that even possible? How do we determine whether particular historical events or people are good or bad without a biblical perspective?

Someone may argue that a figure like Adolf Hitler is widely regarded by almost all people, Christian and non-Christian alike, to be evil. Therefore that demonstrates the existence of a common “natural law” standard for judging historical figures.

But wait just a minute. In the 1930s there was no consensus that Hitler was evil. In fact, he was supported by millions of people in Germany and he had numerous admirers in other countries as well. It was only after he lost the war that he was regarded everywhere as being evil. If he had won the war, Hitler would have likely remained popular, at least in Germany.

From a biblical perspective, Hitler was evil right from the start. But from a “natural law” perspective (whatever that means), things aren’t so obvious. As Ouweneel writes: “If a person is a radical Christian, let him look for an equally radical Muslim or Hindu, and try to find out how much ‘natural law’ the two have in common!” Natural law does not provide a clear and objective standard for determining right and wrong. But the Bible does.

Ouweneel describes 2K’s usage of natural law as follows:

“Such a Scripture-independent natural law is nothing but a loincloth, a fig leaf, to hide the shame of refusing to acknowledge Christian philosophy, Christian political science, a Christian view of the state, etc.”

Two kingdoms in the Bible

Now, the Bible does teach that there are two kingdoms. However, they are not the kingdom of God and a “common kingdom,” but the kingdom of God and the kingdom of Satan (Matt. 12:25-28).

According to Ouweneel, every societal relationship (e.g. family, school, business, political party, etc.) is either a part of the kingdom of God or a part of the kingdom of Satan. As he puts it:

“in every societal relationship, the kingdom of God can be, and is, manifested if this community is, in faith, brought under the rule of King Christ Jesus and under the authority of God’s Word.”

This means that a political community where the citizens and government have placed themselves under the authority of the Bible manifests the kingdom of God. There are historical examples of such communities:

“The kingdom of Christ did indeed clearly come to light in various German lands and European countries (Scotland, England, the Netherlands) in which Protestant convictions dominated public life (sixteenth and seventeenth centuries).”

Clearly, the early Protestants did not believe 2K theology. And as Ouweneel asks,

“Can you imagine John Calvin telling the city council of Geneva that they had to be ‘neutral,’ and that for their rule it did not matter whether they were Christians as long as they were good rulers?”

The key issue

Ouweneel sees the dispute over 2K coming down to one key point: “This is the issue: either God’s Word has full authority over the entire cosmic reality, or only over a limited part of it: the church.” For 2K, the Bible is authoritative only over the church. It does not have authority over politics and government or the other spheres of the “common kingdom.”

The real-life consequences of 2K are serious. As mentioned, it undermines the rationale for Christian schools. Another effect is to remove all Christian influence from political life. As Ouweneel points out, 2K plays

“…into the hands of all the atheists and agnostics who propagate the neutral, secularized state and wish to restrict religion to the church and to the private religious lives of people. The growing number of non-Christians in North America should be thanking their new gods for the support they are receiving from NL2K advocates with their commitment to a secular state.”

Conclusion

The consequences of embracing 2K theology would be devastating to Christian influence in politics and society. Public policy in Canada, the United States and other Western countries has been moving in an increasingly anti-Christian direction for years. If Christians were to abandon their distinctively Christian efforts to influence government, that trend would only get worse. Yet that is what 2K theologians essentially advocate.

Abraham Kuyper was certainly correct that Christ is sovereign over every square inch “in the whole domain of our human existence.” Excluding the Bible from certain spheres of society is a recipe for accelerated decline and ultimate disaster. As Ouweneel puts it, “All talk about a so-called ‘common kingdom’ means in the end that we allow the kingdom of Satan to prevail in the public square.”

Michael Wagner is the author of “Leaving God Behind: The Charter of Rights and Canada’s Official Rejection of Christianity,” available at Merchantship.ca.