There are many classics I mean to read in my life, but I just haven’t yet. Fortunately this summer, while laid up with an injury, I found myself facing Augustine’s Confessions without an excuse. So I dove into it. And I was quite shocked – not by any of his confessions, but how readable it is. You always imagine classics to be quite unreadable, which doesn’t really make any sense, because how could anything become a classic unless people read it? But whatever the case, this classic is engaging.

FREE TO QUESTION

The best thing about the first few chapters is all of Augustine’s questions. Instead of doing what most books do, which is pose a question (such as ‘Why does a good God allow evil?’) and then immediately answer it, Augustine just begins with posing questions. Many chapters start with a block of questions directed towards God, and Augustine doesn’t even pretend he has answers to most of them. If he has part of an answer, or a thought about the answer, he’ll say it, but it’s not from a position of authority. His bits of answers are not presented as definitive. He just lets his mind go wild with wonder over God.

I’d give a few examples, but to baldly state the questions in my own words destroys his beautiful wording of them. I’ll just say one or two – for example, haven’t you ever wondered whether you have to know God first before you cry out to him, or if you can cry out to him in order to know him?

And haven’t you ever wondered how a God who’s outside time, and created time, experiences time?

AN ATTRACTIVE HUMILITY

The unexpected thing about this is Augustine is such a revered figure in the church. He’s more or less the ancestor of many of the churches that exist. So much of Christian theology has roots that go back to his writings. So I expected him to present himself as an expert.

It was refreshing because I haven’t read a book that admitted it didn’t have the answers for a long time. Most often people write books because they do think they have the answers. Or they write because they think people need the answers, so they cobble together some kind of explanation. They know their book won’t attract our precious divided attention if they don’t make bold claims.

But Augustine shocked me because he’s not presenting himself as the pattern the Church after him should follow…even though the Church does. (At least, he doesn’t present that way in the first part of Confessions.) If anyone has a right to make bold claims, it would be Augustine, of all writers.

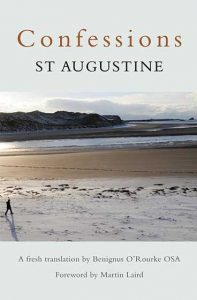

Some translations of Augustine’s “Confessions” can be easily found online and downloaded for free. But the free versions often have older language, with “Thees” and “Thous.” A more current, very readable (but not free) version is Benigus O’Rourke’s translation pictured here. – JD

This is not to say Augustine is completely uninterested in answers. No, in fact much of his search for God is driven by his dissatisfaction with the answers given by his pagan worldview. And finding a few answers was central in his conversion – he explores answers more and more the further you delve into his book.

However, the questions never stop. In the end, he is willing to have faith without answering every question that could be asked about God.

QUESTIONS ASKED IN FAITH

The second really cool thing about Confessions is that, unlike if I was the one asking the questions, Augustine is able to ask them without a trace of cynicism. He doesn’t resent God for not providing answers to all of them. Somehow Augustine is able to put down all his wonderment with the deepest humility, and in a fever of steadfast love. He’s asking because he loves God. He wonders because a person is obviously interested in the ones they love.

I can only hope I present a similar attitude one day.

If someone had wanted me to read Confessions before now, they should not have described it as Augustine’s autobiography, or however else people describe the book. They should have said, “Here’s a guy who lived a couple thousand years ago, who has a mind that works just like yours.” It’s crazy to reach across the centuries and find a thought pattern that feels familiar.

And as for the unanswered questions? This is what Augustine says about them:

“Let [people] ask what it means, and be glad to ask: but they may content themselves with the question alone. For it is better for them to find you, God, and leave the question unanswered than to find the answer without finding you.”