There’s a lot of things you think of when Christmas comes to mind. Christmas tree, Christmas pudding, Christmas presents, Christmas lights, Christmas services, Christmas carols. One of the words you don’t tend to connect with Christmas is truce. What’s a “Christmas truce”? It sounds like a feuding family that makes up for the holiday season.

Yet in 1914, the phrase Christmas truce had power, perhaps more so than any of the other phrases that you typically associate with Christmas.

Ground to a halt

The First World War had started a few months earlier, and after significant early victories by Germany that pushed France to the verge of defeat, the war had ground to a stalemate. The Allies and the Germans faced off over hundreds of miles of trenches that stretched from the Swiss border all the way to the English Channel.

The two sides faced off against each other with their respective trenches separated by a no man’s land. If you raised your head above your trench just a bit too much, someone in the trenches opposite would probably shoot you. If you were ordered out of your trench to attack the other side, well, you were likely shot before you could make much progress across the area between the trenches. The no man’s land was a forbidding area, littered with the corpses of soldiers.

This stalemate had gone on for months. Many of the men had signed up for a brief bit of adventure fighting the enemy, thinking everyone would be home for Christmas. It didn’t quite work out that way.

Soothing music

As Christmas approached, the war ground on, slow, deadly, and lacking the purpose and enthusiasm it had once had. Yet, Christmas Eve that year was different than what anyone might have expected. Gunfire, according to reports, ceased around noon that day.

Both sides of the conflict had received cards and small presents from home. For English troops this included a present from Princess Mary, a tin with tobacco, cigarettes, or sweets, among other items.

The Allied troops on the Western Front heard Christmas carols floating across no man’s land. The Germans sang Silent Night, in German, of course, and the Allies responded with The First Noel.

In one place, the English were alerted to the truce when a German voice called out in English, “English soldier, English soldier; a merry Christmas, a merry Christmas!” What was seen up and down the line was Christmas lights, and small trees. A man displaying Christmas lights on a small tree makes himself vulnerable because his enemy now has a clear target to aim at. Yet the English troops didn’t take advantage of the German vulnerability, apparently because it was Christmas.

A present exchange

Despite the objections of the officers, both sides emerged from their respective trenches, meeting in the middle. They shook hands, and exchanged some of the small presents they had received from home. Communication had its problems, but a number of the Germans had worked in London before the war started, and that helped things along.

There is even talk of at least one game of soccer starting up between the two sides, though this is hard to confirm. Though it’s not known for sure if it happened, it’s fascinating to imagine soldiers who had shot at each other only a few hours earlier now trying to score goals on each other.

Reason for the season

As strange as all this is, what you really have to wonder is why. Why did this happen? There have been spontaneous truces in all kinds of wars, but those tended to be localized and were generally a chance to help the injured or recover bodies of fallen comrades.

This time was a bit different. At about the same time, more than a hundred thousand soldiers scattered over hundreds of miles put down their weapons and not only tolerated their enemies picking up their wounded from the battlefield, but actually went and celebrated with them, singing songs and giving gifts.

Some have suggested that the truce was due to war weariness, since this long, grinding war had been going on for months with little progress and little hope of ending. If that’s all that was involved, surely there would have been more truces on the Christmases of 1915, 1916, and 1917 as the war seemed less and less hopeful and more and more soldiers grew weary of it.

The only explanation I can find that makes sense to me is that this was a different time, when Christmas meant more than good feelings, time off from work, a lot of food, and time spent with the family. This was a holy time that was about the celebration of the birth of a Savior who promised to alleviate our sufferings and reconcile us to God. Christmas Eve was a “night the angels sang,” and so Pope Benedict XV urged that at least on this night, “the guns may fall silent.”

Maybe some stopped shooting because the pope asked them to, but I suspect many more, this early in the war, simply couldn’t ignore the incredible significance of Christmas. While it’s hard to shoot someone at any time, it seemed impossible to shoot someone on the night when God Himself came to live among us.

To learn more

- History.com’s “Christmas True of 1914”

- Imperial Warm Museums’ “The Real Story of the Christmas Truce”

- TheSmithsonian Magazine’s “The Story of the WWI Christmas Truce”

- Sabaton’s Christmas Truce, below, is a unique account by this heaven metal band.

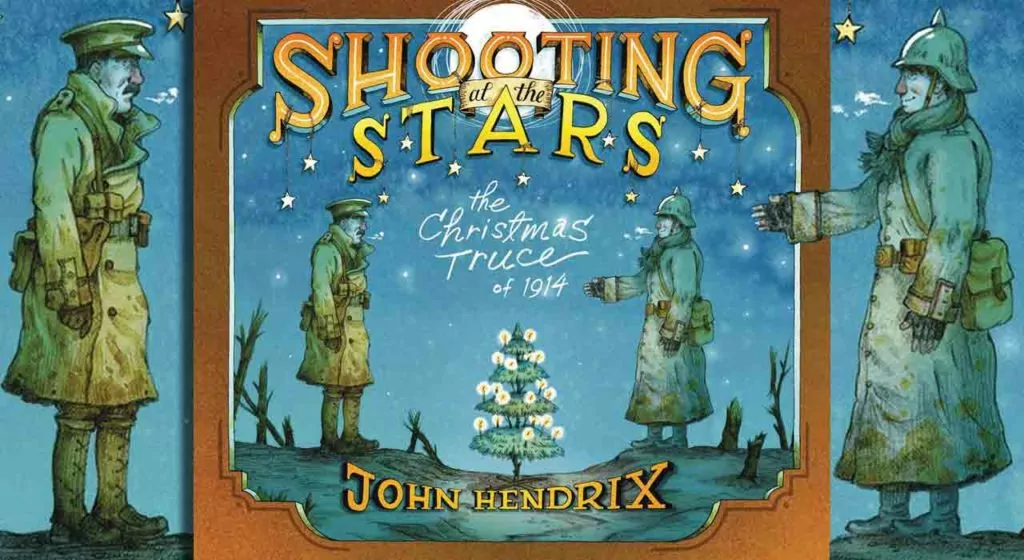

James Dykstra is a sometimes history teacher, author, and podcaster. This article is taken from an episode of his History.icu podcast, “where history is never boring.” Find it at History.icu, or on Spotify, Google podcasts, or wherever you find your podcasts. Picture at the top of the page was originally published in “The Illustrated London News,” January 9, 1915, with a caption that read: “British and German Soldiers Arm-in-Arm Exchanging Headgear: A Christmas Truce between Opposing Trenches….Saxons and Anglo-Saxons fraternising on the field of battle at the season of peace and goodwill: Officers and men from the German and British trenches meet and greet one another. A German officer photographing a group of foes and friends.”