A book worth chewing on…but not swallowing whole

UNDERSTANDING GENDER DYSPHORIA: Navigating Transgender Issues in a Changing Culture – by Mark A. Yarhouse – 191 pages / 2015

Christian leaders have a new, helpful and thorough resource available to help them respond to the recent phenomenon known as “gender identity disorder” or “gender dysphoria.” Understanding Gender Dysphoria is authored by Dr. Mark Yarhouse, a clinical psychologist and Hughes Chair of Christian Thought in Mental Health Practice at Regent University. He has a long career of counseling those struggling with gender dysphoria, a condition in which the person feels there is some sort of disconnect between their biological sex and the gender they feel they really should be – they are men who feel like they should be women, and women who feel like they should be men.

Yarhouse’s book brings a Christian perspective to the issue that avoids simplistic answers and embraces and grapples with the psychological and theological complexity. Yarhouse engages with an incredible amount of social-scientific and medical research, but avoids the pitfall of producing a merely clinical document. Rather, he emphasizes pastoral sensitivity and challenges the Christian reader to walk side by side with people struggling with their identity.

OVERVIEW OF THE BOOK

There’s a lot in the book, so let’s begin with a quick overview. Understanding Gender Dysphoria is written for a Christian audience, a fact made obvious by the dedication on the first page: “To the Church, the Body of Christ.” Yarhouse is motivated by a desire to see the Church proactively grapple with this issue and help those who desperately need help.

He has a lot of criticism for the “culture wars” mentality, which tends to be too simplistic in its engagement of issues like transgenderism. He lays the groundwork by explaining what exactly gender dysphoria is and how complex of an issue it really is. He then delves into Scripture, and wrestles with a number of different texts, analyzing them in light of their historical or literary context and applying them to the issue. He spends a chapter on the causes of gender dysphoria (the short answer is, we just don’t know!), a chapter on its prevalence and how it manifests, and a chapter on prevention and treatment. Throughout these chapters, Yarhouse cites the latest studies, and is careful to note strengths and weaknesses in the reliability of those studies. He makes it clear that much more careful study is needed.

Yarhouse ends his book with two chapters on a Christian response, one at the level of the individual and one at the level of the institution. Here he enters the pastoral realm and gives suggestions for better ways in which Christians and churches can compassionately assist and walk alongside transgendered neighbors.

GENDER IDENTITY CONFLICTS: THREE LENSES

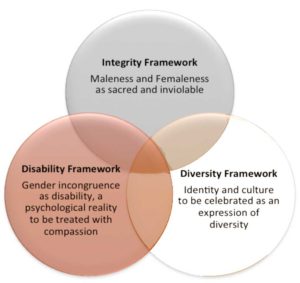

A theme that runs throughout the book is an analysis of three frameworks or “lenses” through which different groups see the issue of transgenderism and gender dysphoria. It’s helpful to explore these in order to understand the starting point for how the various groups in society view and understand the issue.

All three perspectives have something to offer, and also have limitations. After discussing them, Dr. Yarhouse proposes his own fourth “lens” or framework, which includes aspects of the other three. So what are these frameworks?

1. Integrity framework

The integrity framework is probably the lens through which most Christians, as well as most orthodox Jews, and Muslims, view the transgender issue. This framework understands gender in terms of the sacred integrity of maleness and femaleness. We are our biological sex, and there’s no changing that. God created mankind as male and female, equal in dignity and worth, yet with distinct and complementary roles.

But you don’t have to be religious to believe that our gender is stamped on us and unchangeable. A naturalist (one who denies the supernatural) might simply note that in nature we see humankind and the animals as being a binary species: male or female markers are imprinted on each and every one of the trillions of cells of each human and animal body.

According to the integrity framework, men and women are to conform to, and live in accordance with their biological sex.

Scriptural backing for the integrity framework can be found in the creation account, particularly in Genesis 2, and also some Mosaic prohibitions in Deuteronomy against cross-dressing, as well as Jesus’ teachings in the gospels and Paul’s teaching in his letters to the Ephesians and to Timothy. Meanwhile, the naturalist can look to the consistent testimony of biology, DNA and chromosomal data, as well as abundant social-scientific evidence to confirm the binary biological differences between the sexes.

Are there any limitations or potential pitfalls to this approach? Well, holding exclusively to this view might leave a person liable to seeing all male/female differences as unchangeable, including those that are actually just gender stereotypes (i.e. women are bad at math, men are bad at cooking). It might also lead some to overlook and dismiss the struggles of individuals with gender dysphoria (as in “He’s a guy not a girl – what doesn’t he just smarten up!”). And it also has the potential to paint all transgender people with the same brush.

2. Disability framework

Another way of understanding transgenderism is through the disability framework. As the name suggests, it focuses on the mental health dimensions of the phenomenon of gender dysphoria, and views transgenderism as a disorder of the mind.

Most Christians would see some value in this framework too. As our society begins to understand the realities of mental health issues such as schizophrenia, multiple personality disorders, anorexia or post-partum depression, then we get a new sense of what gender dysphoria is like.

The potential pitfall to the disability framework is that in presenting the problem as a health one or a medical matter, it might well prevent discussion of any theological dimension. Treatment becomes very clinical; theological or spiritual responses are sidelined. As one transgender Christian said, “By reducing gender dysphoria to a mere medical diagnosis, I felt trapped and robbed of a spiritual solution.”

3. Diversity framework

The diversity framework is the way most social progressives view transgenderism – they see gender dysphoria as a good thing, to be celebrated.

There are two subgroups within the diversity framework. A vocal minority – Yarhouse calls them the “strong” form diversity framework – sees the sex-gender binary as a socially constructed authority structure to be destroyed and eliminated.

But there’s another group within the diversity framework (the “weak” form) that simply seeks to give expression to the lived experience of a transgendered person and to answer two questions of identity and community: “Who am I?” and, “Where do I belong?”

For those who subscribe to the integrity framework and, to a lesser extent, those who subscribe to the disability framework, there are many problems with the diversity framework. We know that our gender is fixed, and, in fact, a gift from God. So any efforts at undermining the reality of gender are to be opposed.

But Yarhouse argues there is still some value in the weak form of the diversity lens, particularly for the Christian community. What can we learn from this framework? Well, Christians recognize that all humanity is disordered. Any honest Canadian would agree that every human being struggles with the brokenness of life, biologically, psychologically, and spiritually. So “Who am I” and “Where do I belong” are important questions that need to be answered. There are answers, and they apply to all, including the transgendered. Indeed, there is a lesson here for broader Canadian civil society: we can give space for expression of struggles and assist with answering deep questions of identity and community without having to go so far as to deconstruct gender or to embrace and affirm new and dangerous social theories.

4. An integrated approach

Dr. Yarhouse argues that we need to take the best of all three of these approaches and create a new framework altogether: what he calls “an integrated approach.” The integrated view recognizes the integrity of the two complimentary sexes as God has created them. It also recognizes the psychological element or disability associated with this issue, which needs to be addressed with compassion. And the integrated approach takes from the diversity framework the understanding that every individual in their particular circumstances and struggles want their experience or struggle to be understood and heard and want to know who they are and where they belong.

The Christian worldview offers a compelling alternative to the approach of the proponents of the “strong” form of the diversity framework, which seeks to deny and destroy all gender differences. Sadly, the strong form of diversity framework has been adopted – without critical reflection and to the exclusion of other perspectives – by too many provincial governments and is now being imposed onto our communities and schools with the force of law.

CAUTIONS ABOUT THE BOOK

A legitimate question can be asked at this point: Is Yarhouse’s integrated model backed up by Scripture on all three points? I think they are, with this caveat: an integrated approach does not necessarily mean taking an equal measure of each of the three views (integrity, disability and diversity). Yarhouse himself seems to favor the disability model first (he is a clinician, after all), informed by the integrity model, with the diversity model adding a smaller piece to the overall puzzle.

Dr. Robert Gagnon, a leading theologian on the bible and sexuality, has offered some push back on Yarhouse’s thought (I commend to the reader his article published Oct. 16, 2015 titled “How Should Christians Respond to the Transgender Phenomenon?”).

Gagnon takes issue with points of conflict between the disability lens and the integrity lens. While he acknowledges the disability lens, Gagnon is concerned that Yarhouse’s use of the disability label might have the unintended effect of accommodating sinful choices, since Yarhouse argues that “the disability lens also makes room for supportive care and interventions that allow for cross-gender identification in a way the integrity lens does not.” To put it in other words, Gagnon is worried that understanding this as merely a disability might lead to treatments that, in themselves, could become sinful behaviors.

It is important to note here that Gagnon agrees with Yarhouse that the mere existence of gender dysphoria is not sin itself. He writes:

I do not view the mere experience of gender dysphoria as necessarily resulting from active efforts to rebel against God… Where I would qualify Yarhouse is in noting a more complex interplay of nature, nurture, environment, and choices. Incremental choices made in response to impulses may strengthen the same impulses.

Gagnon suggests that it is here that Yarhouse departs from the Biblical language by referencing the clear dictates of Scripture in Deut. 22:5, and Paul’s reference to “soft men” in 1 Cor. 6:9-10. Gagnon suggests that while having the internal turmoil over gender identity is not sin, “acting on a desire to become the opposite sex can in fact affect one’s redemption.”

How far should Christians following Yarhouse’s suggestions of compassionate accommodation go? On the one hand, were a man wearing a dress to attend one of our services, his attire should not be our first concern. We can greet him, and get to know him, ask what brought him, etc. The Church is, after all, a place for sinners, so we should be able to accommodate all sorts of seekers. But Yarhouse pushes accommodation further. He talks of intermittent (and often private) cross-dressing as a way for some Christians to manage their struggle with gender dysphoria. But this is no longer accommodating a seeker who doesn’t yet know what God has said about gender. It is accommodating someone who knows God made us male and female, who wants to indulge in sinful behavior on occasion. So Yarhouse doesn’t properly limit the extent of the accommodation the Church should show.

One final caveat: Yarhouse makes repeated reference to the Church rising above the culture wars or abandoning the culture wars on this issue. I do think there is value in the Church elevating our language and avoiding the typical style of the so-called culture wars, by avoiding debates that lack all nuance and are blunt or belligerent (the style of Ezra Levant is an easy target, but there are many on both sides of the debate who engage in this style). That being said, Christians cannot avoid the culture wars altogether – it’s one manifestation of the antithesis. The question is not whether we do it, but how. We must engage with the culture as salt and light. We must engage winsomely and relationally. Perhaps this is what Yarhouse is getting at. But simply because some do the culture wars poorly isn’t any reason at all for Christians to disengage.

RECOMMENDATION

This book was a challenging yet rewarding read. It really opened my eyes to a much fuller understanding of the issue of transgenderism and, in particular, gender dysphoria. It’s pastorally sensitive while also being scientifically grounded and very well researched. Yarhouse is definitely an expert in the field and has given me a deep appreciation for the complexity of the issue. This book does require work to get through, but the payoff is a much better, fuller and more nuanced understanding of the issue than what is readily available through any short-form articles in the mainstream or social media.

With the cautions noted above, I recommend this book for Christian counselors, pastors, elders and teachers.